A trip to Newfoundland/Labrador would not be complete without a visit to Gros Morne. Lesley Choyce tells us more.

Our love affair with Newfoundland was rekindled recently when we were again permitted to travel (without quarantine) from Nova Scotia to the Rock. Both my wife Linda and I had our two immunization shots and were chomping at the bit for some outdoor adventure. By nature, we are coastal people, content on the flatlands as long as there is an ocean at our doorstep. But those stunning wilderness photos of ordinary people perched high on a rock ledge over a breathtaking fjord were just too tempting. We decided we needed to climb a mountain. Western Newfoundland has some of the most rugged wilderness within our striking distance and we had not yet explored Gros Morne National Park, so before fall schedules and teaching responsibilities kicked in, this was our window for travel.

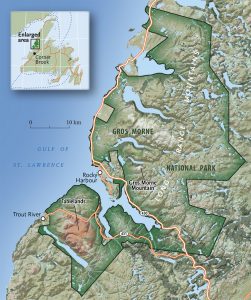

The easy hour and half flight from Halifax to Deer Lake would take us to yet another northern world unlike anything most people experience in a lifetime. I know that sounds like hyperbole but there it is. We would probably never make it to the fjords and cliffs of Norway, but the west coast of Newfoundland would provide challenges enough and it wasn’t going to be just another “walk in the park.” Linda had the lungs, legs, and stamina to master what all the guidebooks called a “difficult” mountain hike, but I have to admit that paddling a surfboard day after day upon a yielding fluid was not quite of the same physical calibre as clambering up the side of a 806 metre mountain. I know that doesn’t exactly sound like Everest proportions, but Gros Morne Mountain is one mother of a challenge.

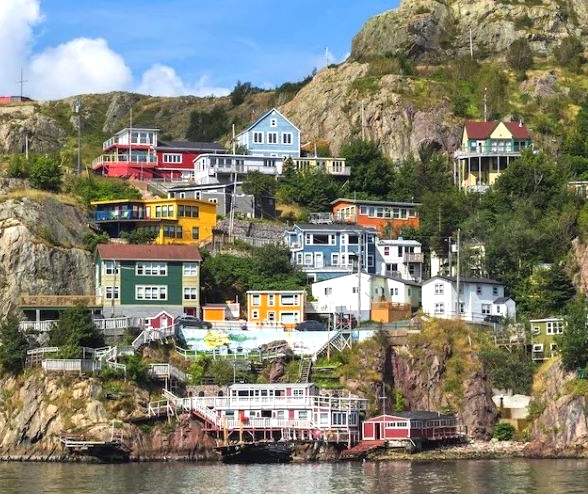

The other thing that drew us to Newfoundland, of course, was the people. It is only one province away, somewhat east and north of where we live, but everything about this island and its people is…well, different. I don’t want to draw on a plethora of clichés to describe how distinctive Newfoundlanders are, but suffice to say that they are uniquely spirited and many who are still in touch with older traditions have a way of thinking, talking, and relating that is exceptional. So, even before we boarded the plane, we dreamed of getting to the top of bald mountain summits high up in the clouds, good feeds of cod tongues and cheeks, possible moose encounters, cascading remote waterfalls, cold pints of Quidi Vidi Dayboil IPA, as well as random conversations with store clerks who call everyone “Luv.” Not to mention the fishermen encountered on wharves who would refer to me as “me son.”

What else could a restless pandemic-weary poet and his leading lady love possibly want?

We had booked a small cottage in Rocky Harbour as our command post and were a bit surprised at how expensive things were in that neck of the woods. Another splash of cold iceberg melt in the face was the cost of a rental car – the cheapest being $100 per day if you could even find one available. Which we thankfully did, as we definitely needed a car to get to our daily wilderness hikes.

Deer Lake airport is a delightfully small affair, as are many tiny airports across Canada. We walked the tarmac to make our way inside and were shocked at the heat. Yes, we had landed in Newfoundland in the middle of another heatwave. We checked in with the COVID squad who approved our documents and within minutes we were packing up the rented vehicle, parked mere inches from the front door of the airport. First stop was the Coleman’s in Deer Lake, a true “northern town.” While Linda shopped for food, I did my usual routine of buying some local craft beer in the attached liquor store. She had requested I find a bottle of prosecco and I couldn’t seem to locate any, so I asked the cashier if they had any, feeling horribly like a know-nothing tourist used to suburban Yuppie comforts. “Never heard of such thing, Luv,” she said. “What is it?”

“Well, it’s bubbly,” I said, now feeling like some wimpish wine dilettante who had no right being in Deer Lake or anywhere further north, so I added, “It’s for my wife.”

“Sure thing, darlin’. Look over here.”

Well, there it was, but it was way too expensive. Below it, however, was a bottle of Friexenit Cordon Negro and I knew Linda would be satisfied with this. “Think I’ll get this one. She’ll be happy with that.”

“Happy wife, happy life,” she said matter-of-factly as I made my way to the till. I had to smile as I had never heard that line before. I also realized that somewhere buried in those few off-the-cuff rhyming words was the echo of the fading days of sexist husband/wife expressions like “my better half” and “the little woman.” Suffice it to say that, back in chic urban Halifax, no one would have said such a thing to my face or if I had used such a phrase, I might find myself immediately posted on Instagram as “The Last of the Haligonian Male Dopes.”

In the seafood section of the grocery store were fresh whole Atlantic salmon the size of small basking sharks for a reasonable price, but it looked like way more fish than we could eat in a week, so we settled for more humble fare, paid our dues and drove north on the 430 towards the beckoning mountains.

Outsiders like us gawk at the many moose warning signs with the iconic image of the full-antlered beast and the accordianed front-end of a sedan. Numbers are posted as to how many moose-related accidents have happened along a given stretch of finely paved roads, encouraging me to keep my eyes straight ahead and my foot trigger-ready to slam on the breaks should the monster suddenly emerge from the forest. But none did.

The drive from Deer Lake to Rocky Harbour is magnificent and the cost of entering the national park is well worth it. Our digs were pretty much in “downtown” Rocky Harbour with a view north towards Lobster Cove Head. We were travel weary despite the ease of the flight and highway drive, so we retired to the oddly swank Anchor Pub in a large modern and oh-so-colourful town hotel. For dinner we had salmon. Go figure.

The first humans to inhabit these shores arrived from Labrador well over 4,000 years ago. They were followed by the Dorset people and later the Beothuk and Mi’kmaq who would have arrived by large, sturdy sea-going canoes from Nova Scotia. When the famed Leif Eriksson arrived around the year 1000 A.D., he encountered inhabitants he referred to as Skraelings. John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto was his real name) generally gets credit for putting Newfoundland (literally) on the map in 1497 and Jacques Cartier landed ashore at St. Paul’s Inlet near Western Brook Pond in 1534. In the years that followed, the Basques and other European fishermen found their way to the Strait of Belle Isle and south into the Gulf of St. Lawrence to hunt whales and other sea creatures. France lay claim to this coast until the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 changed that. Nonetheless, the French were permitted to continue fishing along the west coast and the name “The French Shore” stuck for quite some time. A later treaty in 1783 changed the rules again and declared it illegal for French, English and Newfoundlanders to make permanent settlements here, although many independent-minded people ignored the rules and settled here anyway.

James Cook had once cruised the waters along here to create detailed maps and charts and give English names that are still in use to many of the bays, coves, and inlets. Fish and wood attracted settlers and businesses and, by the late 1800s, there were canning factories in Rocky Harbour, Woody Point, and St. Paul’s, with lumber mills springing up around Bonne Bay. Strangely enough, it wasn’t until 1904 when the English paid the French a sizable chunk of change for full claim to the French Shore that settlements were considered legit.

Although some still thought of western Newfoundland as the forgotten part of the island, towns like Rocky Harbour, Norris Point and Trout River grew and shrank and grew again according to the whims of the economy. And then, of course, Newfoundlanders also became Canadians in 1949 when the province joined Confederation. Later, the establishment of Gros Morne National Park in 1973 would change things dramatically as it now put this chunk of Newfoundland coast on the world map for hikers and nature lovers.

Forecasts of weather in these parts changed by the hour, but Linda had predicted that our first full day on the ground was destined for the Big Climb up Gros Morne as rain was likely to follow in the days ahead. We had already read that, “if you can’t see the top, don’t go.” Many days, the big flat top of the monster mountain is obscured in clouds even on an otherwise sunny day. So that Monday was our day to make a bid for the summit.

We woke early, packed some sandwiches and water and drove a short distance to the nearly empty Gros Morne Mountain parking lot. It was a misty morning, and the top was indeed in the clouds but the sun was quickly burning off the moisture and a few other cars were pulling in with hikers. As I checked to make sure we had enough water, sunscreen, drugstore knee brace for my downhill-troubled knee and enthusiasm, I noticed the other hikers jumping out of their cars, slapping on their back packs and rather rapidly making their way onto the trail. It seemed odd but then, according to the parks people, the round-trip hike would take 8 hours or more on the reported 16.5 kilometre route. (It was advised not to even think about the trek if you slept in late and dallied over brunch.) Clearly these folks were itching to ascend the famous mountain.

Soon, Linda and I were off the tarmac and on the first civilized stretch that would take us to the base of the mountain. Since it was all moderately up and down and had recently been groomed by a small dozer, our discussion focussed on how foolish all the “difficult” propaganda was and what liars those office-bound parks writers were.

I much appreciated the sound of the racing river to our left and the shade of the tall trees on both sides.

At this point, we couldn’t really see the mountain for the trees, so it was just an average walk in the woods and our spirits were good. So, what was there to worry about?

Linda wanted to run the first stretch of the trail, but she kindly hung back to keep pace with me, trying to shake off my sidewalk amble and achieve a more robust mountain-man march. There were streams here and there with what looked like very drinkable water, but I had read in a brochure that one might get some kind of terrible disease caused by beavers peeing in the ponds and streams above. Really? How Canadian that would be, to come down with an infection caused by the national rodent that didn’t have the courtesy to get out of the water before taking a whizz?

A few hours into the hike, we crossed a bridge and hit a few swamped stretches of muddy trail. I leaped from rock to fern stump on the south side and came out fairly unscathed, but my independent-minded spouse took the route less travelled and sunk up to her knees in some primordial black muck that looked like dark chocolate pudding. A hiker behind us laughed when she let out a signature screech and this prompted me to laugh too. (Well, no one was really hurt, right?) This, according to the look on her face, was uncalled for, and a stony silence ensued for the next kilometre or so until we reached the base of the mountain.

Leave a Comment