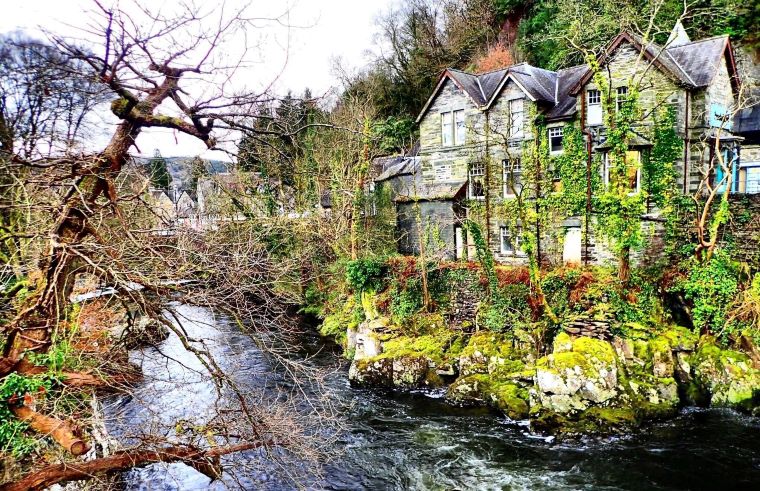

On our first evening in our slate cottage in Betws-y-Coed, I watched as the storekeeps in the Rock Bottom shop closed-up for the day and threw a number of boxes in a green dumpster that shared the same parking lot as our cottage. It immediately drew my curiosity.

My days of dumpster diving were mostly behind me, but not forgotten. My heyday was during an era when no one had to actually padlock their dumpsters. Diving into dumpsters was fun and exciting and as easy as leaning over the metal rail and doing a minor gymnastic manoeuvre to find your way inside for easy pickings of whatever a store would throw away. In North America – back when I was young – vast quantities of reasonably sound goods were heaved daily and, for the most part, no one really cared if young men like me with not much money and a sense of trashy adventure came poking about. But those days were long gone. Now, garbage containers were mostly locked, usually to keep other people from dumping their own garbage into.

But the Cotswold Outdoor Rock Bottom folks didn’t seem worried about who or what might creep into their big green container after hours. And so there I was, leaning far over, feet nearly straight up in the air, rooting through nifty looking boxes that mostly had nothing until I found a very expensive looking shoe box that, lo and behold, held a brand-new pair of running shoes. A small celestial voice inside my head said, “If they are your size, then they were meant for you.”

I grabbed the box, cantilevered my carcass out of the bin, and looked around to see if anyone was watching.

Only the chestnut trees. And they promised they wouldn’t speak a word. Thus, I lodged the magic box under my left arm like an American football and made an end run for the front door of the slate house. Inside, breathing hard as if I had just run a marathon in my newfound running shoes, I opened the box. And there they were. My size; 9 – 1/2. Kind of aqua blue with orange and white soles – a pair of elite running shoes I would never have bought in a million years. But now they were mine. I didn’t recognize the markings. Not Nike, Not New Balance. No. But something strange, something exotic with an upside-down Q and U.

Only the chestnut trees. And they promised they wouldn’t speak a word. Thus, I lodged the magic box under my left arm like an American football and made an end run for the front door of the slate house. Inside, breathing hard as if I had just run a marathon in my newfound running shoes, I opened the box. And there they were. My size; 9 – 1/2. Kind of aqua blue with orange and white soles – a pair of elite running shoes I would never have bought in a million years. But now they were mine. I didn’t recognize the markings. Not Nike, Not New Balance. No. But something strange, something exotic with an upside-down Q and U.

Linda immediately looked them up on the internet with some kind of program that was like facial recognition for shoes. (Who comes up with these sites? And who uses them on a regular basis? I want to know.) It turns out they were called Cloud Surfers. They were made in Switzerland and claimed to be “The world’s lightest cushioned shoe for Running Remixed” whatever that meant. Back in Canada they would have cost nearly $300. I had hit the jackpot.

I loved my new slim, ultra-chic running shoes and expected to find more booty (pardon the pun) every night thereafter. But alas, nothing more came my way as a garbage gift from the Cotswolds. And I will never know why this pair of shoes was in the dumpster but they were going back to Canada with me so I could wear them on campus when I returned and so colleagues around the Faculty of Arts and Sciences would say to each other in the department lounge, “I think there is something different about Professor Choyce since his sabbatical.” Or so I hoped.

That evening while sitting in our cozy den, me with my new footwear, I randomly picked a book from the shelves called The Fragrant Minute by a writer called Wilhelmina Stitch, whose real name was Ruth Jacobs. It turned out she was English, born in Cambridge, and somewhat famous in her day although probably not as famous as Isaac Newton. But she had carved out a writing career in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada as “the poem a day lady.” The editor of the little book had this to say about Ms. Stitch: “Most of us are of common clay. We only desire to walk in seemly paths and live serenely. It may be that Wilhelmina Stitch recovers for us the glamour of half-forgotten days, the sweetness of memories, the buoyancy of childhood. It may be that she reminds us of something fragrant within ourselves of which contact with life is prone to rob us.”

In her poem “The Gift of Day” Wilhelmina writes,

The very minute I awake,

I find, and this is every morn,

A precious gift for me to take

The gift of Day, newborn.

The book also included thirty-one, sort-of-prose poems of a similar vein, each one more optimistic than the one before. I suppose most would find the entries somewhat sappy, but the sentiment was much like the chapter on Buddhism I was reading in Man Seeks God.

The book also included thirty-one, sort-of-prose poems of a similar vein, each one more optimistic than the one before. I suppose most would find the entries somewhat sappy, but the sentiment was much like the chapter on Buddhism I was reading in Man Seeks God.

“Live in the present. Be kind. Be compassionate. Don’t grieve or remain attached to losses. Celebrate each and every little thing.”

Right on, Wilhelmina. Her books have been relegated to those large and mouldering dustbins of literature, I am sure, but there is nothing quite like sitting in a warm slate cottage in Betws-y-Coed wiggling my toes inside some really comfortable $300 running shoes that I snatched for free with my loving wife and dog nearby and reading a gushy early twentieth-century Winnipeg optimist who published a poem a day and became famous for it. Perhaps her work will be resurrected by some future graduate student at the University of Manitoba, or even Cambridge itself, and brought back into the folds of pop culture just at some distant depressing moment when all hope for humanity seems to be fading like the last pink dregs of a Prairie sunset.

Most books found in rental houses are pretty banal; romances and thrillers and murder mysteries in large type for old geezers like me to read without the need of glasses. But here were more than a few gems. Not great tomes about the history of syphilis like back in Little Walden but a good assortment including Born to Run by Christopher MacDougall, which is the best book on running that I have ever read and contains an enlightening chapter on how the modern running shoe with all of its mechanisms to protect the human running foot has done more damage to feet than if we ran barefoot. Fortunately, the author explained why post-modern footwear like my newfound Cloud Surfers had minimal arch support and a fairly thin soul allowing the foot-brain connection to flourish as it had with our ancestors whose very survival depended upon the ability to outrun in bare feet whatever monstrous creatures of our shrouded past would try to eat us on a daily basis.

And as I rooted around in this wonderfully fecund little library, I also found a local book titled The A-Z of Betws-y-Coed by Donald Shaw published by Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. (Say what?) Under “B” I discovered that the Black Plague visited the valley here in 1349 during the reign of Edward I. Did the damn plague find its way to every nook and cranny of Europe and the British Isles? I had already studied up on this Black Death or Bubonic Plague and knew it had wiped out a hundred million or more unwary people in Europe and Asia. Maybe if the locals could have kept visitors (and visiting rats that carried the infected fleas) away they might have been spared. But they were not. Reading about the disease, I made a mental note that if I came down with vomiting, fever, headaches and swollen lymph nodes any time soon, I would go directly for treatment as you would probably die from the plague within a week of exposure if not sooner.

If you had survived the plague, you may have produced children who would have had children or grandchildren who would have been around in 1468 when the town was bashed by the Earl of Pembroke in what historians like to call the War of the Roses. You can be forgiven if that sounds like the name of a terrible movie from the 1980s you once saw pitting Kathleen Turner against Michael Douglas. The real war was not about a marital squabble that went ballistic but about two competing factions for royal domination; the Plantagenets (white rose) and the Lancasters (red rose, like the tea).

I have read lengthy explanations about what this “civil” war was about, but I don’t see it as my task to try to explain or make sense of the endless bloodshed and fighting that seems to have occurred on every square foot of the U.K. To summarize, however, I would say the fighting was because people were unhappy, the white roses blamed the red roses and vice versa, there was a certain amount of greed and lust for power, and common folk were easily duped into fighting for whichever side they sided with. History reports there was mental illness involved on the part of both families as well. If you care to know more, the library can supply you with the necessary details but I am just a guy with his feet up in Snowdonia looking for some background on where I am plunked down.

I have read lengthy explanations about what this “civil” war was about, but I don’t see it as my task to try to explain or make sense of the endless bloodshed and fighting that seems to have occurred on every square foot of the U.K. To summarize, however, I would say the fighting was because people were unhappy, the white roses blamed the red roses and vice versa, there was a certain amount of greed and lust for power, and common folk were easily duped into fighting for whichever side they sided with. History reports there was mental illness involved on the part of both families as well. If you care to know more, the library can supply you with the necessary details but I am just a guy with his feet up in Snowdonia looking for some background on where I am plunked down.

Alas, I will just jump ahead to the more important details of the twentieth century.

For example, there was a “problem” with gypsies in Betws-y Coed in the 1930s. The problem was that the “travelers” kept showing up and the locals did not like them. I found no reports of stolen children or major crime, just minor hustling. Cheating perhaps. Maybe the mean-spirited bartender I had encountered was not even Welsh but the son of wandering gypsies who decided to stay in one place and cheat his clients, letting them come to him instead of him following in family footsteps to find new marks.

But to leave Betws-y-Coed’s history on a gentler and positive note, author Shaw writes that in 1951, “Postwoman Catherine Roberts retired. It was said that during her years of service she had walked the equivalent of twice around the world.” That’s a lot of walking and it led me to wonder how many shoes she had worn out and what kind of shoes were they? This would have been in the days long before Cotswold Outdoor Rock Bottom and the other fashionable outdoor footwear establishments invaded the town like modern day rose warriors.

1951, I noted, was the year I was born, which, I suppose, means nothing at all, except that it was a year when some of us – me in particular – were just coming into this world.

Our eager parents were hoping that all the wars were over and a bright peaceful future lay ahead while retiree Catherine Roberts, who had served her community faithfully, was hanging up her postal walking shoes and looking forward to a quiet afternoon sipping tea beneath blooming Welsh wisteria while studying the new growth of her hydrangeas flourishing in the front yard.

In the morning, Linda ran back and forth on the main drag of Betws while Kelty and I walked up into the forest behind the house. We passed Taverners – a hostel for young hikers who were sitting out at tables in the bright sun eating fresh fruit and granola. Here again was the young tribe of hikers that rather fascinated me. There were a lot of them here in town and it brightened my day. Sure, they had what looked like unwashed dreadlocks, and they were tattooed and had odd bits of metal sticking out of unlikely parts of their faces. But they were young and free (maybe) and had arrived here without cars and with only what they could carry in their voluminous nylon backpacks. Some were probably rock climbers, some bicyclists and some purebred hikers who were about to walk to the tops of Moel Siabod, Moelwyn Mawr or climb Snowdon itself. God love them, these granola-munching, long-haired, eco-friendly tourists who didn’t give a hoot about video games, designer jeans, long-term employment plans or the latest Donald Trump news gossip.

Further along the road, Kelty and I breathed in the pure forest air and observed the spears of morning sunlight filtering through the hemlock branches, using this elixir to cure some morning worries about my daughter about to have twin babies back homes. I had to work hard to quell the shouting voices in my paranoid parental head. But as everything seemed, while not ideal, very much under control in Canada, I reconfirmed my faith in the Canadian medical system and my trust in the support Pamela had around her. We had a backup plan for leaving if we had to. I said several simple prayers for my child and her imminent offsprings’ well-being, and then I tried to quiet my mind.

For today, at least, we’d stick with our plans. And, as for me, today I was going surfing.

And not in the ocean. Any ocean.

And that would be a first for me.

Dolgarrog is a short drive north along the Conwy River from where we were staying. It is an unlikely place for an inland surfing park but there it is – Surf Snowdonia, “the world’s first artificial surfing lake.” Part of me didn’t like the idea of surfing an artificial wave. Why? Because it’s artificial, that’s why. Those modern hippie hikers wouldn’t have thought much of me I bet if they knew I was about to pay a hefty fee to surf a man-made wave. But I probably would not be back this way again and there was indeed a wave here – a reportedly surfable, head-high wave.

I had been surfing since I was thirteen and never given it up. In my book, once a surfer, always a surfer. Age would never be an issue.

Why the surf park was in Dolgarrog is a bit of a mystery to me. Travellers come here for the mountains, the climbing and the hiking. There would be skiing in the winter, of course. But there is not a great population base like other places in the world where “surf gardens” were cropping up. But I guess there was a good water supply and carloads of summer tourists willing to give predictable surfing a go. So, for one morning, I would join the inland surfers and see what it was like.

-Story by Lesley Choyce

Leave a Comment