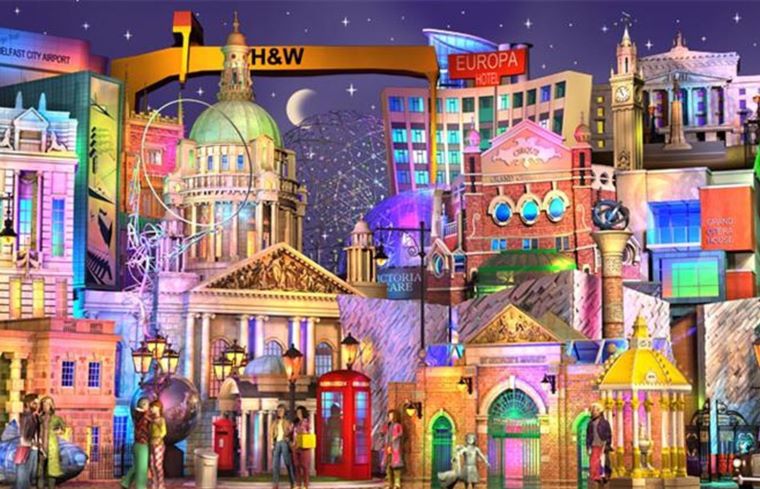

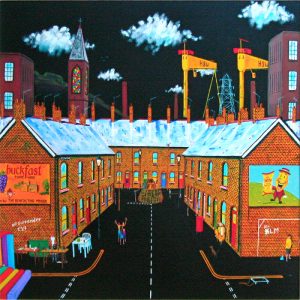

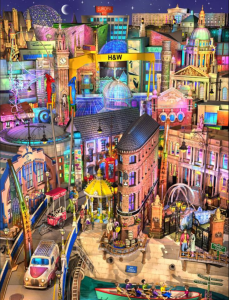

In Belfast Hymn, a joyous evocation of the city’s 5,000-year history, Pulitzer Prize- winning poet Paul Muldoon celebrates its crowning achievements with an affectionate tour of its most familiar landmarks. It is filled with what the celebrated writer calls ‘the spirit of hope and the idea of home’

“A sandbar near a river mouth”

would give Belfast its name.

The river where we’ve slaked our drouth

and where we staked our claim

with those who built the Giant’s Ring

five thousand years ago,

with Normans, Essex, the Dutch king,

with Chichester & Co.

For even Ptolemy the Greek

set his sights on the Lagan.

He used to come for the Twelfth week

despite warnings of “dragons.”

Although we’re sometimes seen as staid

we’ve tossed our bowler hats

and cheered on every new parade

across the tidal flats.

The Vikings gave us a wide berth

and focused more on Larne.

They’d overrun the Solway Firth

and ransacked Lindisfarne

so they had nothing left to prove

about their derring-do.

We’d kept the Picts at some remove

despite their being True Blues.

What really put us on the map?

The world viewed through the prism

of eggs and bacon in a bap.

It’s a Belfast Baptism!

It’s seen us through our darkest hours

and salved our troubled souls.

Since we were granted devolved powers

we’ve all been on a roll.

Although we’ve so much on our plate,

Although we’ve so much on our plate,

we take it as a badge of honour

to eat twice our weight

in wheaten farls and fadge.

What sets the Ulster Fry apart

is its calorie count.

It’s a clear insult to the heart.

The casualties mount

from Portavogie to Ardglass

where they’ve given up erring

on the side of caution, alas,

determined to prove herrings

and prawns will happily coexist

if served on beds of dulse.

The reason why they hold your wrist?

To check if you’ve a pulse!

For Belfast’s long been a byword

for hospitality –

the slice of barm brack, lemon curd,

the drop scones at high tea.

It’s for sponge cakes and Sally Lunns

we Belfast people yearn.

A spot of bother?

All “wee buns,” as far as we’re concerned.

Most of the things we love to share

are made with Cream of Tartar

though any putting on of airs

is a complete non-starter.

It’s Adam’s Ale straight from the tap

that we still most esteem –

unless it’s Châteauneuf-du-Pape o

or Costières de Nîmes.

Although it’s true we do enjoy

a pint and a wee Bush

restraint’s the technique we employ.

We just don’t like to push

unless it’s with a certain tact,

like when we’re simply forced

to read someone the riot act

for backing the wrong horse

or give our caddies an earful

when we’ve kicked up a divot

or into a Titanic hull

hammer those white-hot rivets…

That great ship waiting to be launched

was set off down the slip

by men like us. Stalwart. And staunch.

And taking no auld lip.

That smell’s the smell of retting flax

from County Down flax dams.

Some sheets are sewn from old flour sacks

but some are monogrammed.

For from the cradle to the grave

we wear our linen bleached.

We see it breaking like a wave

on a North Antrim beach

where some diehards still like to surf

and some fish in chest-waders.

We know that artificial turf

is favored by Crusaders

along with polyester mesh.

In times of joy or grief,

of course, there’s nothing quite so fresh

as a fresh handkerchief.

Belfast Ropework Company,

the largest in the world,

kept us from being all at sea.

The Queen of the May birled

her leg and hunkered down to caulk

a seam with hanks of goat hair

even as she scanned the Lough

for Shorts’ new flying boat.

It’s known Shorts aircraft had a fin

sometimes described as “ventral.”

Known, too, the best of days begin

and end at the Grand Central

where we counter the cold and damp

with oatmeal, ancient grains,

entrecôte aux champignons, champ,

a flute of gold Champagne.

The flute on which James Galway soared

was really made of gold.

Some dwell in the House of the Lord

and some on the threshold

of hotels like the Maritime,

Van Morrison and Them

summoning from our glow and grime

melodious mayhem.

When Sam and Dave fell foul of Saul

they took refuge in Naioth.

For us there’s no escape at all

from Samson and Goliath

except perhaps to lose ourselves

in big band and bebop

as we go thumbing through the shelves

of a used vinyl shop.

Those two iconic gantry cranes

have held us in their thrall

long after they’ve thrown off their chains

or we’ve had any call

for their great feats of strength

or other shows of force.

History holds us at arm’s length

until the Dutch King’s horse

charges us from a gable-end

charges us from a gable-end

and Henry Joy McCracken

expounds on all that might impend

while on Cavehill the bracken

brings us right back to the Bronze age

and a cauldron’s dull glow.

It’s time to check the pressure gauge

in case the whole thing blows.

And what we cherish, it would seem,

are the rough and the smooth

of Brillo Pads, Brylcreem,

tang, tungsten, tongue and groove,

the Sliced Pan, the Sliced Plain, plain fegs,

jaw-box sinks, wheelie-bins,

the goatskin bodhráns, the Lambegs

made from their kith and kin.

When we bake apple tarts or pies

we keep it in the family.

The apple on which we rely

would be an Armagh Bramley,

resistant as it is to scab.

We ourselves resist blabs, blowhards,

gasbags with the gift of the gab

(unless it’s our own bards).

For though we’ve lost some afternoons

drinking from a tin can

in the snug Crown Liquor Saloon

beloved of Betjeman

we’ve also found our poets best

sustain us with their words.

Now we’re known less for snipers’ nests

than nests of singing birds

we laud the poetical wing

where Mahon, Longley, Hewitt,

McGuckian, and Carson ring

out the seed-bells, suet,

and bacon rind they’ve set in store

against our winter wants.

We track them still on the foreshore

by their typewriter fonts.

Our painters, too, have seen the light

where water meets the sky.

Cadmium Red. Titanium White.

How often have they vied

for supremacy in the air?

Andrew Nicholl giving a vague

sense Cavehill might still shelter bears.

Tom Carr, James Humbert Craig,

Dermot Seymour’s footrot- and fluke

ridden sheep, William Conor,

Rita Duffy, the great John Luke

whose many selves we honour

as we struggle with points of view

and depth real or perceived.

They come at us out of the blue

where sea-heave meets land-heave.

Though the green hills lie on all sides

we come back to red brick.

Short, narrow streets run far and wide

as if they were homesick

for Manchester or Birmingham

and not Dublin or Cork.

In times gone by we’d run ram-stam

with pikestaffs and pitchforks

across those cobble-littered streets

and then put on the kettle.

Long years of beating a retreat

have made us show our mettle

and muse at length upon the stuff

we’re made of. Granite. Gault.

We jubilate in being gruff

and gracious to a fault.

We like to get down to brass tacks,

the no-frills nuts and bolts,

but not before we’ve had some crack.

We do tend to revolt

against whatever powers might be.

We rejoice in high jinks,

gooseberry jam, Nambarrie tea,

Irwin’s malt bread, Kerr’s Pinks.

Some like potatoes “balls of flour”

and some prefer them waxy.

Some hire a limo by the hour

and some hop a black taxi

to visit those old trouble spots

on the Shankill and Falls

before taking one last straight shot

back to the City Hall.

For years we found it hard to wean

ourselves off giving vent

to something very much like spleen

against those we resent.

But now we harbour not a grudge

but something more like hope.

Even the hardest heart will budge

when we throw it a rope

unless it fears being pinned down

like that high-profile giant.

That doesn’t play in Sailortown.

That makes us more defiant.

We revel in the linen mills

and the yarns they still spin.

Though on all sides lie the green hills

we’ll never be hemmed in.

For if the future’s less than clear

that won’t leave us nonplussed.

It’s not our style to live in fear

of what’s in store for us.

Our shipyard workers packed their gear

and a “piece” in a box.

But now it’s peace we’ve engineered

and christened in the Docks.

The spirit of those men of steel,

The spirit of those men of steel,

their gray-eyed wives and daughters,

will keep us on an even keel

through the uncharted waters.

For we steer by the Northern Star.

However far we roam,

that “river mouth near a sandbar”

will signal we’ve come home.

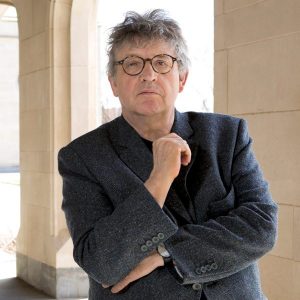

Paul Muldoon is an Irish poet, described as being ‘the most significant English-language poet born since the Second World War’. He has won many awards, including the the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry 2003 and the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry in 2017. www.paulmuldoonpoetry.com

Leave a Comment