Just as his entitled children band together in an effort to swipe the old man’s legacy from under his nose, they find that their father has outmaneuvered them, selling his dynasty to billionaire tech guru Lukas Matsson (Alexander Skarsgård) and leaving them to sink or swim on their own merits. It’s a scintillating tease of the fourth and, as showrunner Jesse Armstrong recently confirmed, final season, which sets Logan and now Cox up as free agents at the top of their game.

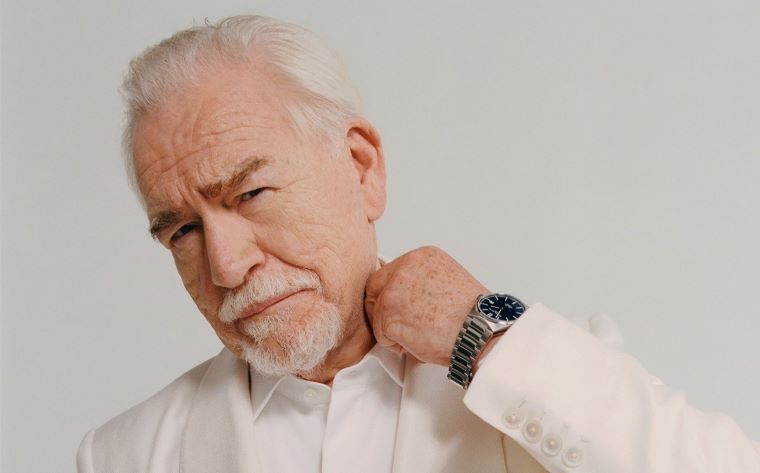

Speaking by Zoom a few days after Armstrong’s announcement — and soon after the publication of a set of duelling media interviews in which he and co-star Jeremy Strong expressed different perspectives on the merits and demerits of the latter’s method acting — the 76-year-old Cox sounds optimistic and light on his feet, open to the promise of life and work post-Succession as much as Roy is basking in the afterglow of his big deal. “It’s a stop along the way,” he says demurely about the Emmy-nominated and Golden Globe-winning role that has altered his trajectory from theatrical heavyweight and self-identified character actor to one of the biggest stars in prestige television. He’s willing to grant that Logan “slots in perfectly well” next to characters such as Lear, Titus Andronicus, Hannibal Lector, and Winston Churchill already in his portfolio. While he admits he’ll miss him, calling him “one of the great roles,” Cox isn’t all that anxious about saying goodbye, applauding showrunner Armstrong for his rather un-American fortitude in refusing to let the series run past its sell-by date: “There is,” after all, “a world elsewhere.”

That lack of preciousness is a recurring theme with Cox, as he frequently returns to the idea that work is practice, even at his age, and that the best way to build an oeuvre is to forget your ego and do your job. “I love working,” he says of his delight in projects as varied as theatre and documentary voiceover work as he spitballs what he might do next, sounding less like someone at the end of a definitive chapter in their career than like a working actor filling out his dance card. In a moment of supercharged cultural discourse about so-called nepotism babies in the industry coming by their careers through industry connections, Cox holds court as the always-occupied star of stage and screen who came from humble means in Dundee, Scotland. He carries himself with the ease of a self-made success who, like Logan — and unlike the ungrateful scions he calls his children — has made his own pile. “I’ll have a go at anything,” he admits about his eclectic resumé. “I love that aspect of the work that is available to me. I see it in terms of another human being that I have to create, that I have to have respect for. And I don’t want to worry into a kind of morass of sentiment.”

As a social democrat who has spoken out about the importance of social welfare programs and grants for artists like him in his youth, one might assume Cox’s respect for a garrulous, super-rich, right-wing kingmaker like Logan to be minimal. But he speaks reverently of his character’s survival instincts, his ability to weather scandals and shifting political tides and stay firmly himself. “You can’t get around Logan in the sense that he has done it,” he admits, comparing his hard-won victories to the easy, inherited ones of his children. And while Logan has settled into a politically conservative cocoon — his news network ATN generating hard-right discourse and playing kingmaker with presidential hopefuls — Cox feels that has more to do with his opportunism and business acumen than any deep-set convictions, suggesting that Logan’s humble origins might just as easily have pushed him leftward, as they did his brother Ewan (James Cromwell). His rightward swerve, Cox thinks, is not the result of destiny but curdled expectations: “That’s all to do with his disappointment. That’s all to do with his disillusionment, with everything.”

When pressed about whether selling the company isn’t an existential failure for a character who pointedly un-retires in the pilot episode after viewing a fawning magazine cover of his supposed heir, Kendall (Strong), Cox insists that Logan has a clearer endgame in mind than the viewer might appreciate. “He’s realized that in order to move forward, you have to go back,” he says of Logan’s opaque motivations in breaking up the company he’s jealously guarded. “It’s not a straightforward path. You have to rest, go back, and retrench. That’s why he is successful, because he’s retrenched in the past, and he’ll retrench again.” Amidst Logan’s many strategic advances and retreats, Cox is most impressed by the solidity and completeness of the character on the page. “It’s a very economic role, and that’s what the appeal is. He doesn’t dissipate. There’s nothing dissipating about Logan.”

Like the legion of loyal HBO and Crave subscribers who have shared memes about which of the wastrel kids will get the coveted kiss from daddy each week, Cox is forthcoming with his opinions about the relative strengths and weaknesses of the Roy children. “I think Logan is disappointed because none of his children have stepped up to the mark,” he says in defense of his decision to blow up their inheritance ahead of the final season. Cox reads lone daughter and ex-political strategist Siobhan (Sarah Snook) as Logan’s favoured successor. She’s smart, he concedes, “but she’s such a flake. She can’t stop talking. She cannot discern and she cannot keep secrets. She lets everything out.” Kendall’s ongoing vulnerability, meanwhile, keeps him from scoring high on the power rankings, which have recently seen the rise of a new player in Logan’s long-suffering son-in-law Tom (Matthew Macfadyen), who Cox sees as, if not a successor, at least “the catalyst for any movement forward.”

Given that Shiv and Kendall have flamed out, who might Cox have favoured in Logan’s Lear-like succession plan if he hadn’t sold the whole thing to Matsson? He slips in and out of Logan’s voice as he admits to his soft spot for Kieran Culkin’s cocky, damaged, satyr-like Roman, the dark horse second son — or third, if you count Alan Ruck’s drippy Connor, though Logan doesn’t seem to — who legal counsel Gerri (J. Smith-Cameron) dryly describes as “bootleg Logan.” Roman, Cox feels, shares his own character’s killer instinct, but is “tragically self-defeating,” undone by his “potty mouth” and penchant for sending ill-advised dick pics at strategy meetings. Most of all, Cox thinks Roman takes himself out of the running by partnering with his siblings in the finale only to then have the audacity to talk of love. “Love has never been on the agenda,” Cox scoffs, as if offended on Logan’s behalf. “Logan would have loved some love. He is shocked. You behave like a bunch of Judases, and you talk about love? They’re very out of order.”

In the end, like the protagonist of a revisionist romantic comedy, Logan chooses the known quantity: himself. “He’s had to deal with these people for such a long time,” Cox sighs, “and none of them have shown any real vision of what Waystar should be. I think it’s a needs-must situation. He’s not getting any younger. He feels that he needs his business to be taken care of. And they have proved wanting in their abilities to take care of it.”

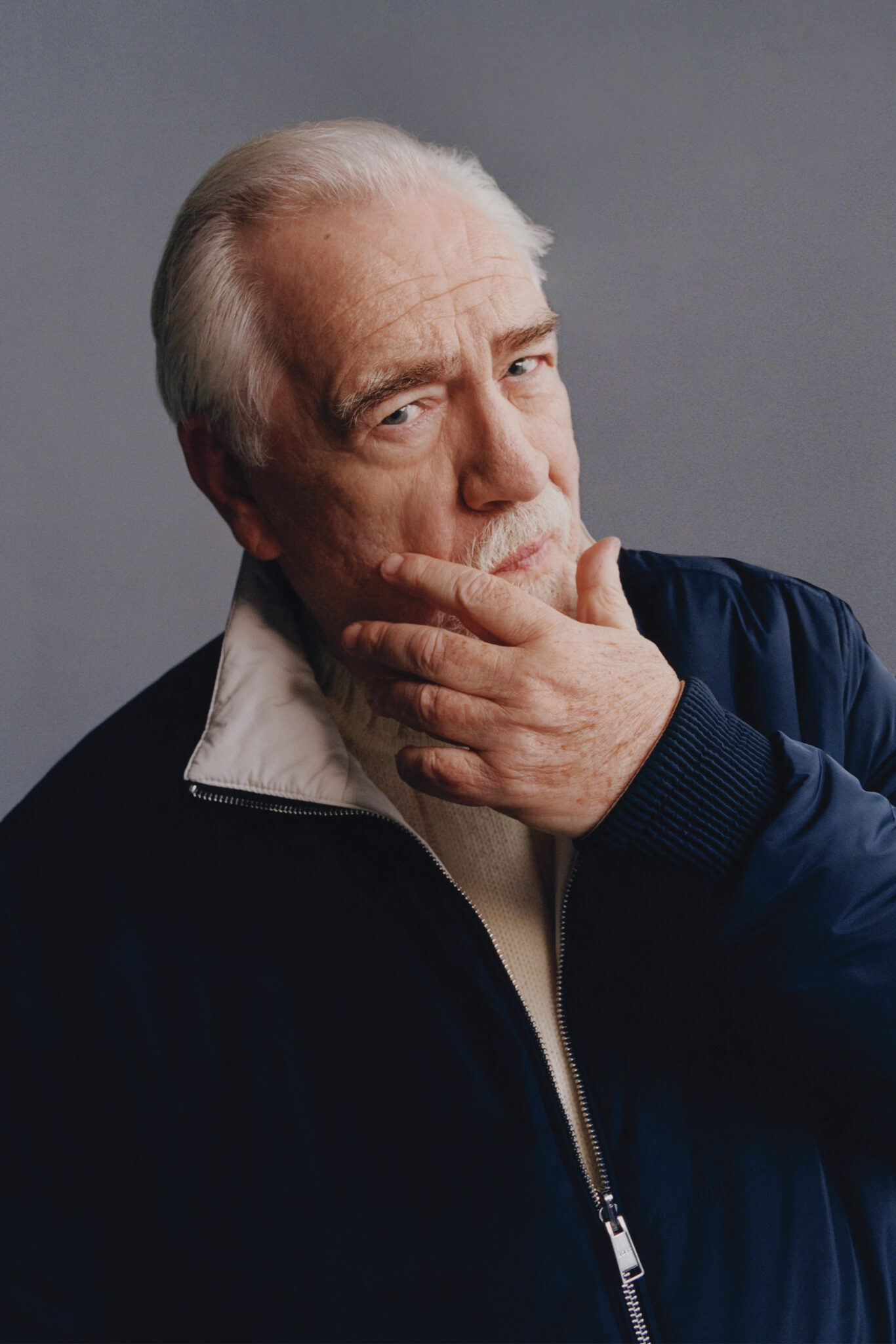

Caretaking is important to Cox, whose aversion to method acting stems partly from the belief that it can gum up the process of an art he insists requires a “lightness of touch,” making a performer rigid and inflexible, and encouraging them to forget their place in the production. If method actors burrow into the emotional lives of their characters, identifying totally with them at great personal cost — as well as passing on residual costs to their cast mates and crew, who are locked out of that process — the matter-of-fact Cox prefers to roam, in service to the cast and writers’ developing vision. “In a show like Succession,” he says, “you don’t just have the responsibility of character. You’ve got a responsibility to what the ensemble is creating. You have to be dexterous.”

Dexterity for Cox means realizing where you are in the moment and responding in kind to what both the cast and the creatives behind the camera are putting out. “You need to have a healthy attitude where you can shift at a moment’s notice,” he says, “especially to working with writers who are going in a certain direction while you might want to take it in another direction.” That tug-of-war, he feels, tends to go against one of the unwritten rules of the actor-writer relationship. “The deal is you go the direction that the writer wants to go, not taking it your way. There are ways of doing that. But the way to do it is to play the role, and to do it rather than worry it.”

Despite their philosophical differences, Cox is politely complimentary, even gentle, toward Strong, noting that most of the method actors he’s worked with have been good at what they do. “I allow other people to be who they are,” he offers obliquely when asked if there’s a benefit to bouncing off the energy of actors who approach the work differently. “If that’s what does them good, fine.” He’s more caustic about one of Strong’s inspirations in the method acting pantheon, Daniel Day-Lewis, with whom he worked in Jim Sheridan’s The Boxer. Cox expresses bemusement at the three-time Academy Award winner’s brief retirement after that experience in 1997 — burned out and prematurely soured by the work on the verge of middle age, which he insists ought to be the outset of the most fruitful years of one’s career. “That’s when the roles start getting better,” he exclaims. “Ibsen, Chekhov, Shakespeare, Lear, Andronicus, The Master Builder, John Gabriel Borkman. Those are the roles you should be working up to. I’m going to be playing James Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey Into Night next year, and I just think this is where I’m supposed to be. This is what I’m supposed to do. It’s my job to play these roles and give them the credibility they deserve, not to make these roles a burden I carry.”

Despite their philosophical differences, Cox is politely complimentary, even gentle, toward Strong, noting that most of the method actors he’s worked with have been good at what they do. “I allow other people to be who they are,” he offers obliquely when asked if there’s a benefit to bouncing off the energy of actors who approach the work differently. “If that’s what does them good, fine.” He’s more caustic about one of Strong’s inspirations in the method acting pantheon, Daniel Day-Lewis, with whom he worked in Jim Sheridan’s The Boxer. Cox expresses bemusement at the three-time Academy Award winner’s brief retirement after that experience in 1997 — burned out and prematurely soured by the work on the verge of middle age, which he insists ought to be the outset of the most fruitful years of one’s career. “That’s when the roles start getting better,” he exclaims. “Ibsen, Chekhov, Shakespeare, Lear, Andronicus, The Master Builder, John Gabriel Borkman. Those are the roles you should be working up to. I’m going to be playing James Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey Into Night next year, and I just think this is where I’m supposed to be. This is what I’m supposed to do. It’s my job to play these roles and give them the credibility they deserve, not to make these roles a burden I carry.”

As for his own future after Succession — beyond that upcoming West End production, as well as a turn as Johann Sebastian Bach in a production of Oliver Cotton’s play The Score for Theatre Royal Bath — Cox seems loose and modest, eager to follow his beloved mother’s advice to him whenever he’d get too worked up about a role: “Brian, it’s only a play.”

“I’m up for grabs,” he chuckles about his openness to a wide range of projects when reminded of all the credits he’s accrued over the years not just in theatre but also in horror films and action thrillers. Over the coming months and years, he says, he’s planning not just a return to the theatre — “to see if I can remember my lines anymore,” he adds, self-deprecatingly — but to direct a film as well.

Still, nearly sixty years into his career, it’s the opportunity acting affords to practice and play that grabs him. But even as he stresses that acting is not the “religious experience” for him that it is for others who insist on a total identification with their characters, at the expense of looking around from time to time to appreciate “the totality of what we do,” he underscores that it is a profession that requires you to put in the time. Perhaps, he suggests, it’s made all the more rewarding because it requires both lightness and commitment, a strong sense of self as well as a willingness to surrender it in service of the work. “It’s a discipline. It’s a craft. The greatest musicians do it delicately. They play the instrument, and the music comes through, and they allow that to happen. But they don’t get in the way of it. They don’t marshal it to their own id.”

Story by Angelo Muredda / Source: sharpmagazine.com

Is/was there no Irish actor, from Ireland, that could have been written about in length?