Hey there, you. Yes, you, the one reading this – how’re you doing? In all my years writing for this publication, I have hardly asked you, the reader, how things are going in your life. With the last two years of lockdowns and pandemics and social turmoil I thought it might be a good time to check in and see how you are making out.

Given how tough things have been lately, the topic of mental health has been on our minds here at Celtic Life International. We hear it a lot from those we interview: that COVID-19 has been a trying influence on their careers and personal lives. We have also heard it from our readers, and our colleagues, friends, and family. It is affecting everyone.

On the one hand, this is an unprecedented number of people who are struggling with a shared mental health crisis – the Lockdown Blues, if you will. However, we live in an age where the mental health struggles of our neighbours are less mystified and more empathized with than ever. In many ways, we are lucky to be dealing with this enormous bummer today, together, all around the world.

Because mental health – including in the Celtic world – has not always been as understood as it is today.

For millennia – indeed, for much of our recorded history – mental illness was a mostly misunderstood malaise of the human condition. In the worst cases, people who may well have suffered from illnesses we understand today – schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, etc. – may have been hunted as werewolves, or burned at the stake as witches.

Even as we became less superstitious and more scientific in our approach to medicine, we were still largely groping around in the dark, especially when it came to the mysteries of the mind. In the 18th century, for example, ailments were believed to all derive from one of the four humours – black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood – and depression in particular was believed to be caused by black bile. (Literally, the word melancholy comes from the Latin words for “black” and “bile.”)

As for treatment, options ranged from flim-flammery propositioned by non-medical laypeople in many cases, to what – for the time – counted as genuine medical best practices of heroic therapeutics; “evacuations, blood-letting, cathartics, purgatives, emetics, blistering agents, camphor, opium, warm and cold bathing, mercury, anti-spasmodics, belladonna, and digitalis,” according to Therapies for Mental Ailments in Eighteenth-Century Scotland, a study published by the University of St. Andrews in 1998.

Though one of the most prevalent and pernicious solutions to mental health problems in the Celtic nations – as well as much of the rest of the world – which lasted well into living memory was the use of lunatic asylums. “Out of sight, out of mind,” as they say.

“I do a lot of genealogy, and I discovered, when I dug back through the centuries, people in my family, historically, have been admitted to what were called ‘lunatic asylums,’” Langlands explains in a Zoom call from Dundee.

“It possibly has nothing to do with mental health – it was simply the way people were treated back then.”

Tom McEneaney became certified to practice mental health care in Belfast at the age of 24. Now 65, he has over four decades of experience in the mental healthcare system of Northern Ireland. He remembers the asylums.

“When I started training, the stigma associated with mental illness was massive,” he explains. “We had all these big mental health institutions which were on the edge of big cities, with 1,500-1,600 beds in them. Most of those institutions now are almost all closed.”

Much improvement was made in the medical understanding of mental illness in the 20th and so far in the 21st centuries, of course. We now know that unusual and self-destructive behaviour is not caused by demonic possession or an accumulation of phlegm – instead, the roots are often in the balance of neurotransmitters, and the existence of past traumas.

Despite this awareness, the biggest hurdle to battling mental illness in the modern era is the stigma that McEneaney hinted at. Folks still just don’t like to talk about their feelings.

And in places like Northern Ireland, or Scotland – Celtic cultures, that value the stoic, strong, and self-sufficient – that stigma was especially daunting.

Tony McLaren is the national coordinator of Breathing Space, a Scottish mental health support line that works with people in moments of dire need.

“We will get people who are on a bridge, wanting to take their own life,” shares McLaren, who explains that Breathing Space opened its doors in 2004 to provide an after-hours line of support for Scots in crisis, largely in response to a startling statistic about Scottish men. “At that time, 75 per cent of our suicides in Scotland were male. That statistic has not changed, insofar as we still have around 70-75 per cent of those people taking their own lives – completing suicide – being male.

It is a similar story in Northern Ireland, says McEneaney.

“That gets you wondering, what is it about Scottish men?” he ponders. “What is it about our Celtic nature? Is it alcohol? Is it emotional intelligence? The inability to speak about our emotions and our feelings? Because we’re tough Scotsmen, y’know?”

“In Northern Ireland, we are one of the highest instances of mental health concerns across the whole of the U.K.,” he posits. “We are probably a 25 per cent higher rate of mental health conditions, and depression is the most common health issue across the isles. We have also had, the last six years, the highest rate of anti-depression prescribing in the U.K. And that is across all age ranges.”

That’s perhaps not surprising, given Northern Ireland’s violent political history. A 2002 study, Mental health in Northern Ireland: have ‘the Troubles’ made it worse? By D. O’Reilly and M. Stevenson, suggests that the nation should expect to see a wave of mental illness in the ensuing decades.

“Violence, accompanied by greater delinquency, may also result in increased social disorganisation, a growing mistrust and an erosion of social capital in communities that will further predispose people to psychological stress,” the paper reads. “There is some evidence that this has happened in Northern Ireland as it is now an extremely polarised society where more than two thirds of the population live in areas with more than 80% of one religion. Spatially segregated societies like this tend to have a disrupted psychology of place and this can cause a sense of alienation and eventually anger and resentment, leading to confrontational interaction and further violence.

“It will be interesting to see if the higher levels of psychiatric morbidity in Northern Ireland fall with time and an improving political situation.”

Today, McEneaney doesn’t deny the impact of the Troubles, but stresses that the reality is more complicated than that.

“Coming out of the Troubles, and the trauma associated with the Troubles, is a factor. But it is not the only factor,” he explains. “A lot of it would be to do with lifestyle – there is a lot of low mood and depression in young people. There is a high suicide rate especially in young men in Northern Ireland. Alcohol and drugs play a role. Also, the pressures that people feel now, and may not have felt in the past. Maybe working conditions and unemployment. High levels of social deprivation.”

McEneaney currently serves as the head of business development and support services for Aware NI, a Northern Ireland charity for those suffering depression and bipolar disorder. Aware NI has 25 cognitive behavioural therapy-based support groups across the region, most of which are face-to-face; a decade ago, 80 per cent of those who showed up to support groups were women. That figure has changed in recent years, however.

“What we have found out, last year alone, was that 52 per cent were female, and 48 per cent were men,” says McEneaney. “There’s a big swing of men seeking help. That can only be good.”

Why the change? The likely answer is simply that the stigma around mental health is beginning to fade.

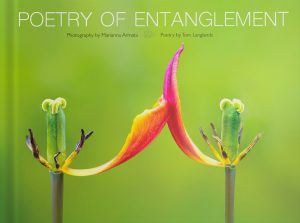

Langlands recently published a book of poetry, called Poetry of Entanglement. Teaming up with his Canadian friend and collaborator Marianna Armata – who contributed complimentary photography – the pair intend to split their profits 50/50 between the Canadian Mental Health Association and the Scottish Association for Mental Health (SAMH).

“I have had several friends who have suffered from mental health issues and received treatment for them; I had one particularly good friend during the midst of COVID-19 who actually ended up in a bit of trouble with mental health and needed to seek help. But I have noticed, in recent years, a very comforting shift to people being able to talk about it much more than they ever did before. If I go back to my childhood, you never spoke about it. It got brushed under the carpet. Over the last year or two, I have the people I know who are struggling – people who wouldn’t have spoken about it in the past – are opening up more.”

“I have had several friends who have suffered from mental health issues and received treatment for them; I had one particularly good friend during the midst of COVID-19 who actually ended up in a bit of trouble with mental health and needed to seek help. But I have noticed, in recent years, a very comforting shift to people being able to talk about it much more than they ever did before. If I go back to my childhood, you never spoke about it. It got brushed under the carpet. Over the last year or two, I have the people I know who are struggling – people who wouldn’t have spoken about it in the past – are opening up more.”

That change could be thanks, certainly in part, to organizations like Aware NI and Breathing Space, being public-facing organizations who have been advocating for mental health awareness for years or even decades.

“It is to give them fertile ground, so they can feel safe,” says McLaren. “I have had many men tell me, ‘I’ve never spoken about this to anybody.’ “Given the right environment, men will talk about their thoughts and feelings.”

In addition, the proliferation of technology – especially communications tech – has allowed treatment to occur over vast distances, and in the privacy of one’s home, if one prefers. The access to mental health support has grown exponentially in the last few decades. That makes a difference in awareness, which in turn dissipates the taboo.

“I never thought technology would be as important as today,” McLaren admits. “I have had to churn up my skills around using Zoom and Microsoft Teams and web chat in order to engage with people. I work with footballers who are playing for Ross County, Inverness, Aberdeen, and Dundee. I would never really have seen them as it was too far away. Now they can exchange and have therapy over Microsoft Teams.”

Having worked to get tablets and Breathing Space-connected phones in places like prisons and holding cells across Scotland, McLaren says that technology is bound to continue to evolve alongside our understanding and treatment of mental illness.

“There was something in therapy around, ‘we have to see one another; we have to shake somebody’s hand; we have to be in the same room,’” he explains. “That has been a change just over the last two years. Some psychodynamic services are saying, ‘we don’t agree with it.’ Well, get on board, because this is what’s going to happen.”

Much of this technological growth in the last two years has been exacerbated and propelled by the sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a trauma the whole world is going through, and much like the shared trauma of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, this pandemic is sure to send ripples through mental health in the coming years.

“The COVID-19 pandemic is a global health emergency, the scale, speed and nature of which is beyond anything most of us have experienced in our lifetimes,” reads a 2020 study, Mental health impacts of COVID-19 in Ireland and the need for a secondary care mental health service response, by Karen O’Connor, Margo Wrigley, Rhona Jennings, Michele Hill and Amir Niazi.

“The mental health burden associated with this pandemic is also likely to surpass anything we have previously experienced.”

The paper continues, “This pandemic will be associated with an increase in people presenting for the very first time with significant mental health difficulties. Several groups are likely to be particularly vulnerable,” such as COVID-19 survivors, people bereaved during the pandemic, frontline workers, and those with fewer social and economic resources. “People with established mental illness are likely to be particularly vulnerable to relapse, exacerbation of symptoms and impaired functioning in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

The study urges that the need for ring-fencing a budget both for mental health services, and for COVID-19 mental health research to prepare for the coming wave of mental health issues on the horizon. However, since we are all experiencing it, there should also be a huge increase in empathy related to mental health struggles.

“Our own health minister said he expects a ’tsunami’ of mental health issues after the pandemic,” says McEneaney. “The good thing about the pandemic is, it’s got people talking about mental health. When people talk about mental health, it reduces the stigma. There is a big attitudinal change now, that it is okay not to be okay, and it is okay to talk about it.”

McLaren, who earlier pontificated on what makes the Scottish man susceptible to mental illness, also figures that the Scots’ tendency towards being a good and hospitable neighbour will shine after the pandemic.

“I think COVID-19 brought that out, as well – how we are actually kind in our communities today. The family across the road and the old lady next door. I might be biased, though – I am Scottish through and through. With young people I see with my colleagues – maybe it is the environment I work in, that is where the bias comes in – that people want the best for their neighbour.”

“I suppose it is like anything – once people open up about it, others will then help and assist them getting the support that they need,” adds Langlands. “That is what I am finding happening with some of my friends. It was something of a taboo 10-20 years ago, but now it is far less of a problem to talk about it. That’s the silver lining.”

Story By Christopher Muise

Leave a Comment