To illustrate quite how low-key the person I’m going to be writing about is, let me start by telling you about someone else. Let me tell you about Martin. Martin is the taxi driver the fates assign me at Dublin Airport when I arrive in Ireland the day before the interview with the person I’m going to be writing about. Once the car doors are closed, Martin wastes no time in indicating to me that he, like the person I’m going to be writing about, is a little bit famous. Unlike that person, Martin is not low-key.

“Google ‘Dublin taxi-driver same-sex marriage’,” he instructs me, as we careen southwards into the city. But I don’t need to, because Martin’s already telling me about the time in 2015 when he was asked by an Australian news channel for his views on the imminent referendum in Ireland, deciding whether to permit same-sex marriage. His response, described by the reporter as “trademark Irish humour”, was this: “I’m in favour of same-sex marriage because I’ve been having the same sex with the wife for the last 30 years.” It got “millions of views on YouTube”, says Martin, but apparently his wife wasn’t too happy. “It was actually 35 years,” he admits. Classic Martin.

And what brings me to Dublin, Martin wants to know? Well, Martin, I’m interviewing an actor. Irish. Lives here.

“I’m a film buff,” says Martin.

OK, then! Have a guess.

“Gabriel Byrne.”

No.

“Brendan Gleeson.”

No.

“Liam Neeson?”

Still no, but he’s been in films with all thr–

“GOBSHIIIIITE!!” Martin yells out of the window at a woman crossing the road in front of his taxi, who scrambles back to the curb.

He’s been in films with all three.

“Jonathan Rhys Meyers.”

Nope.

“No, no! I’ve got it. Colin Farrell.”

Nuh-uh.

“James McAvoy.”

Martin, he’s not even Irish.

A lightbulb above Martin’s head flickers into life. “Aah, Peaky Blinders! Cillian Murphy!”

Bingo, Martin. That’s your man.

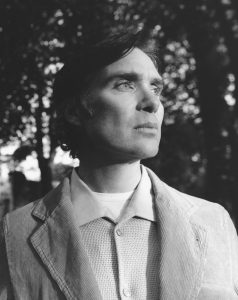

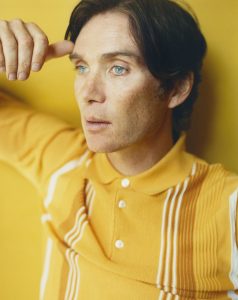

It may not seem like it, but it is testament to how discreetly Cillian Murphy goes about his business that he is the seventh name on Martin’s list of Irish (and one Scottish) actors. This despite having been in some of the most memorable films of the last two decades, including Danny Boyle’s zombie apocalypse classic 28 Days Later and Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy; turning in multiple acclaimed and gut-wrenching performances on stage; and starring in one of the most fanatically adored British TV shows of the current era, Peaky Blinders. Murphy is not an actor who seeks attention outside of his work — in fact, he responds to it like the jaywalking woman to Martin’s front bumper — and his quiet resistance to the showiness of show business has enabled him to lie low. Thus far, at least: in February, Murphy will start filming Nolan’s new biopic, Oppenheimer, which might well be the biggest role of his career.

It may not seem like it, but it is testament to how discreetly Cillian Murphy goes about his business that he is the seventh name on Martin’s list of Irish (and one Scottish) actors. This despite having been in some of the most memorable films of the last two decades, including Danny Boyle’s zombie apocalypse classic 28 Days Later and Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy; turning in multiple acclaimed and gut-wrenching performances on stage; and starring in one of the most fanatically adored British TV shows of the current era, Peaky Blinders. Murphy is not an actor who seeks attention outside of his work — in fact, he responds to it like the jaywalking woman to Martin’s front bumper — and his quiet resistance to the showiness of show business has enabled him to lie low. Thus far, at least: in February, Murphy will start filming Nolan’s new biopic, Oppenheimer, which might well be the biggest role of his career.

The morning after my thrill-ride with Martin, I take a local train to the suburb where Murphy lives. The tracks run past glitzy tech-company headquarters, then modest residential streets, before the buildings fall away and we’re skimming the shores of Dublin Bay. I get off in a leafy seaside neighbourhood made up of quietly expensive, elegant houses and a parade of single-storey shop-cum-cafes. It’s in one of these that I’ve been instructed to meet him, though I spot him in the street outside and wave him down. He’s dressed in dark colours, a cagoule over a striped T-shirt, dark jeans and boots, with his hair in the floppy style he seems to favour when the choice is his own; his sunglasses, which he quickly removes, are the only hint he’s trying to be inconspicuous and, paradoxically, that he’s famous.

“How do we do this?” he says, when we’re face to face (which we are almost exactly; I’m 5ft 7in and he’s about the same). I suggest we do an elbow tap and, as happens when you do an elbow tap, we look immediately ridiculous, like apprentice Morris dancers. Inside the cafe, we take a table in a room at the back.

Murphy has been living in this neighbourhood, which he refers to as “the poor man’s Riviera”, since 2015. After 14 years in London, he and his wife, Yvonne McGuinness, an artist, decided to come back to Ireland so their two sons, Malachy, now 16, and Aran, 14, could be raised here, closer to their grandparents and away from the “pressure of living in a massive city”. There was also, at the time, the whiff of the Brexit referendum in the air. “It wasn’t informed by that,” he says, “but we felt like rats from a sinking ship, a little bit. Ha! It was the right time to come back.”

“It’s quiet,” he says. “I like it, where I am now in life. Wouldn’t have been that exciting in my twenties.” His house doesn’t exactly have an ocean view — “from the top of my son’s bedroom if you stand on your tip-toes” — but, he says, “we’re quite close, and it does make you feel instantly decompressed in some way. I think it’s good for the old Happiness Index.”

In person, Murphy exudes modesty, though even “exudes” might be too forceful a word. His voice is smooth and soothing, as listeners of Cillian Murphy’s Limited Edition, his occasional show for BBC Radio 6 Music, will know; so, too, will users of the Calm meditation app, on which he reads a purposefully boring story about travelling by train across Ireland (“Limerick Junction has been a key turning point on the Irish rail network since it opened over 170 years ago…”) that is supposed to lull you to sleep. (I can confirm that, if you’re interviewing him the next day, it is less effective.)

Murphy is between projects when we meet and his regime during these fallow periods sounds enviable: reading, watching movies, listening to music. Every day, he goes for a walk or run with the family Labrador dog, Scout. He does it, he says, “more for my head now”, though he used to run competitively. (I’ve interviewed him once before, a decade or so ago, and by chance the next day we were both running the same 10k. I had looked up his time afterwards and it was, like, 37 minutes. “It wasn’t 37 minutes!” he says when I bring it up. “I’ve never done it in 37 minutes. No way.” OK, fine, but I remember it was fast.)

Since lockdown, Yvonne has swum daily in the sea. Murphy has been known to venture out in a dinghy. In a low-key way, of course.

“If it was ever as part of a club, I wouldn’t get involved.”

Why not?

“Fucking sailing clubs! It wouldn’t be my thing.”

For months at a time, Murphy’s life can be like this. Quiet. Restful. Serene. But, like the goddesss Persephone summering on Mount Olympus or an ice-cream van man wintering in Tenerife, it’s only one side of the coin. Eventually, it’s time to get back to work.

For months at a time, Murphy’s life can be like this. Quiet. Restful. Serene. But, like the goddesss Persephone summering on Mount Olympus or an ice-cream van man wintering in Tenerife, it’s only one side of the coin. Eventually, it’s time to get back to work.

As Martin will tell you, if there’s one thing he’s done that has tipped Cillian Murphy into the public consciousness, it is Peaky Blinders, which is due to return for its sixth and final season in February. Created by the British screenwriter Steven Knight (Taboo, Eastern Promises), Peaky, as it is known to fans, is the phenomenally successful TV drama series about a criminal gang in Birmingham in the early 20th century and the upwardly mobile working-class family, the Shelbys, who run it. The show is sleek and violent and stylish, all three in the extreme: the lice-deterring haircut favoured by the Blinders — shaved sides, long on top — has become iconic in its own right. It is also, yes, sexy: characters don’t walk down the street in Peaky; they strut in slo-mo, in the V-formation of migrating geese, to a twang of electric guitar.

At the centre of it all is Murphy’s character, Tommy Shelby — or “Tommy fucking Shelby” as he is occasionally, and with considerable justification, introduced — the leader of the Peaky Blinders, who wears his razor-trimmed cap, from which the gang takes its name, low over his eyes and keeps his cards close to his chest. Tommy is the moral heart of the drama or, maybe, the moral vacuum: he runs gambling rackets, he smuggles drugs, he kills in cold blood. But he also defends the oppressed, would do anything for his kids, and is deeply damaged, like so many of the men around him, from fighting in WW1: can he help it if his compass is askew?

“Cillian and Tommy are almost polar opposites,” Steven Knight tells me during a phone call, “and maybe that’s how it works.” Knight likes to tell the story of how, after his audition, aware his natural mien is not exactly gangster-ish, Murphy followed up with a text reading, “Remember, I’m an actor.” “Which I never forgot,” says Knight. “And boy, what an actor.”

From his first appearance as Tommy in the pilot episode, in an immaculate suit, riding a black horse through a Birmingham slum as children and women scramble for cover and the staccato opening chords of the show’s theme song, “Red Right Hand” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, begin to play, it was clear Murphy was right to back himself. “The haircut, the suits, dropping the voice, I used all of that,” he says, matter-of-factly. “These are all just tricks that you figure out.”

“It’s a cliché, but no one else could have been Tommy Shelby,” says Knight. “It would be absurd. It was as if Cillian was always waiting.”

n March 2020, Murphy was preparing to fly to Manchester to shoot the final season of Peaky Blinders. Pre-production was complete; the sets were built. Yet the first cases of Covid-19 in both England and Ireland had already been identified. There were rumours of lockdowns. Murphy and his co-star, Helen McCrory, who had also been in the series since the show began in 2013, playing Tommy’s spunky Aunt Polly, were concerned.

“I do remember both myself and Helen calling the producers and saying, ‘Guys, surely we can’t do this?’” Murphy recalls. “They were saying, ‘Well, we’re still waiting to see.’ And then, eventually, they called it.”

Murphy found himself at home for 18 months. During that time, he “tried to moderate the wine intake just like everybody else”, but largely got through it unscathed. “I feel bad saying it, but we had an OK lockdown. It was nice to be with the kids. There were a few explosions, but we got on mostly.”

In January 2021, it was deemed safe to recommence filming in Manchester, but by then the circumstances were very different. The UK was still in lockdown and Murphy was required to shuttle only between the set and his rented flat. The memory is not a happy one. “It wasn’t a very pleasant shooting experience,” he says, “for loads of different reasons.”

One reason overshadowed all the others. By the time filming began again, it had become apparent, though not publicly, that McCrory was suffering from breast cancer and would not be able to participate. The script would need to be revised and the character of Aunt Polly written out. On 16 April, midway through filming, the production got the news that McCrory had died. She was 52.

“We were just reeling throughout the whole thing,” says Murphy, who still seems in a kind of shock. “She was a dear, dear pal and she was the beating heart of that show, so it felt very strange being on set without her. The difficult thing to comprehend is that, if it wasn’t for Covid, there would be a whole other version of this show with Helen in it. But she was so private and so fucking brave and courageous.

“She was inspirational,” he continues. “People throw that word around, but she genuinely was. Her values, the way she dealt with her kids and Damian [Lewis, the actor, and McCrory’s husband of 14 years]…” He starts slipping in and out of the present tense. “She cares about everybody. She’s really funny and really cool, and she had this real warmth. She really cared. It’s just… I still can’t believe she’s not here. It doesn’t make sense. I’ve never lost anyone like that — who was young and a friend. It was very confusing. But she was magnificent. She was an absolutely magnificent person.”

In the depths of grief, the material provided no solace. “Dark as fuck” is how Murphy describes the show’s sixth series, though he can’t say much more about it. Both Knight and Murphy have talked in the past about the arc of the show leading towards Tommy’s redemption; now, though, Murphy seems unsure. “I think that’s what Steve was aiming for,” he says, “with loads of wrong turns along the way. But I don’t know. I’ll leave that to the court of public opinion. I don’t know if he’s been redeemed.”

So far, the court of public opinion has swayed quite heavily in Tommy’s favour, to an extent even Murphy seems surprised by. “Duality is what I’m interested in, that thing of: how the fuck can he be such a sensitive, good father but commit this heinous fucking act? People are willing to spend an awful long time with characters who, if someone described them to you in daily life, you would say, ‘Keep that person away from me.’ Is it only in television that that exists?”

Maybe it’s a TV thing, but maybe it’s also a Murphy thing. Even playing a character as ethically suspect as Tommy, he seems to inspire in people a strange, protective urge. Steven Knight recalls an encounter at a Peaky Blinders Q&A in New York, which seems typical.

The difficult thing to comprehend is that, if it wasn’t for Covid, there would be a whole other version of Peaky Blinders with Helen in it

“A woman put up her hand and said, ‘You won’t hurt him, will you?’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ She said, ‘You won’t hurt Tommy? You’re not going to kill him or anything?’ I said, ‘I don’t know.’ She was really upset. This makes it sound like this was a mad person, but she was self-evidently sane and normal; she was just so worried his fate was in my hands. In the end, I said, ‘I promise I won’t kill him.’”

Knight has made it clear he intends to write a Peaky Blinders film, which, he tells me, “we’re going to be making in the next 18 months to two years”. Would it involve Cillian? “Yes,” he says, resolutely. “That’s all I can tell you.”

When I mention talk of a film to Murphy, he’s more circumspect.

“Mmm, talk,” he says. “I’m open to ideas. I think he wants to, but I haven’t read anything.”

How, then, does he reflect on his time on Peaky Blinders? “I’ve loved it. It’s only this year that it felt hard. I’m still shocked by how it went from this small little show on BBC Two to this worldwide phenomenon.”

So as far as his contractual obligations go, this is the end? He concurs: “I’m free! Haha!”

I point out that he may never have to wear his hair in the Peaky crop again.

“Gladly never, yeah!” he says.

Unless the film happens.

“We’ll see.”

While the weather is holding, we decide to go for a walk. Murphy suggests heading for the harbour, where he likes to take Scout, up towards a small lighthouse from the base of which you get views across the Irish Sea. As we walk over a footbridge towards the pier, the clouds are rolling in off the water, but rolling past again just as quickly. “That’s why you get that nice light,” says Murphy.

The eldest of four children (two boys, two girls), Murphy grew up in Ballintemple, County Cork, to parents who were both teachers. Their house had “a lot of music, a lot of books”, though his parents weren’t particularly into theatre: a family outing was more likely to be to a traditional Irish music gig. He remembers being “reasonably troublesome” when he was young, “a bit of a mess, a bit energetic”, though he became more introverted as a teenager when, he says, “You fucking mute yourself, don’t you?”

He found an outlet in music, playing lunchtime concerts for the first years at his conservative Catholic boys’ school in a “very Beatles-influenced” band called Sarahdaze, which evolved into another outfit called Sons of Mr Green Genes (by this point, they had discovered Frank Zappa).

Around the same time, aged 16, 17, he became aware of acting as a thing you could do when an esteemed local theatre group, Corcadorca, came to run a drama module at his school. “Me and my pal Bob, who was the drummer in the band, did all these funny sketches. Just messing and putting on voices and things. But it was eye-opening and it felt natural. I absolutely loved it.” In 1995, he saw Corcadorca’s production of A Clockwork Orange, which was staged at Sir Henry’s nightclub in Cork. “It was promenade, techno, dry ice and guys on stilts… I hadn’t seen a conventional play in a proscenium arch or anything. The first thing I saw was that. I thought it was the greatest thing I’d ever seen in my whole life.”

Green Genes, though, were taking off, with a style that was, let’s say, of its time. “We had a tune called ‘Didgeridon’t’,” Murphy remembers. “I wouldn’t listen to a didgeridoo tune now, but when you’re 20…” There’s archive news footage on YouTube that shows a young Murphy, sweaty-faced and wide-eyed, explaining his band’s ethos to the reporter: “It’s a music that’s popular in the ’90s and it’s not constrained by any formula, and that came from the whole spirit of jazz, which is the spirit to express yourself on your instrument, which has been lost…” (“Sounds like a blend of funk, rock and hip-hop to me!” says the reporter.)

In August of 1996, Sons of Mr Green Genes were offered a recording contract by Acid Jazz Records. As it happened, Murphy had just failed the first year of a law degree, for which he’d signed up somewhat reluctantly (“My parents thought it might be good…”), but his mother and father felt his brother, Páidi, who was also in the band but still at school, was too young. By then, Murphy had auditioned for Corcadorca’s new play, Disco Pigs, written by a young Irish playwright, Enda Walsh. He’d also met his future wife, Yvonne. While on a camping holiday in France, he found out he’d got the male lead in Disco Pigs: “They posted the script to my tent.” Green Genes turned the record contract down. It was, says Murphy, “a big month”.

Disco Pigs went on to be something of a phenomenon. The production travelled to the 1997 Edinburgh Festival, where it “didn’t so much debut”, wrote The Guardian, “as erupt”, before transferring to the Bush Theatre in London. Later, it went on international tour, during which Murphy was able to scratch the itch — “staying up late, drinking, going to nightclubs, playing live” — that he was missing from not being in the band. Gradually, though, his path was being set. “I remember, after London, I thought, ‘Right, I’m going to call myself an actor.’”

Murphy’s subsequent career as an actor… Wait. We’re walking along the pier now, and he’s seen someone he knows. A woman with another Labrador.

“Hiya!” he says. Then, when she’s out of earshot, “You know how you know all the dogs’ names, but not their owners’? There’s always a bit of a stand-off between my dog and that one. They’re both males, but one of them tries to have sex with the other.”

And, in those interactions, your dog…

“Mine generally gets mounted.”

Right. Where were we..? Murphy’s subsequent career as an actor has had some notable highs. There was 28 Days Later, written by Alex Garland — and presumably transcribed from his crystal ball — in which a pandemic spreads across the world and causes the population to become rage-fuelled zombies. Murphy watched it with Malachy a few years ago: “I was pretty proud of how well it stood up. He loved it. He was really scared.”

There was Neil Jordan’s Breakfast on Pluto in 2005, in which Murphy starred as a transgender woman searching for her mother, for which Murphy was nominated for a Golden Globe.

There was Ken Loach’s The Wind That Shakes the Barley in 2006, about the Irish War of Independence, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and which Murphy describes as “the purest work I’ve ever done”. And there was Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, released between 2005 and 2012, in which he played Dr Jonathan “Scarecrow” Crane.

Murphy’s relationship with Nolan is one of the most important of his career. Having first tried out as the Batman himself — again, there’s YouTube audition footage out there — he was instead given the role of the fine-boned baddie. He has also played the posh-boy mark whose brain is invaded in Nolan’s 2010 sci-fi heist movie Inception, and the “shivering soldier” (a bigger role than it sounds) in 2017’s Dunkirk. “Chris will just call you up,” says Murphy, of how the roles are assigned, “and I always say yes, because they’re always amazing.”

This year, Nolan called again. Word had already been circulating about a new $100m project, Oppenheimer: an adaption of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography American Prometheus, by Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin, which recounts the troubled life of the theoretical physicist and “father of the atomic bomb”. This time, Nolan wasn’t thinking of a supporting role for Murphy: he wanted him for Robert J Oppenheimer himself.

Presumably, he didn’t have to mull that one over for long. “Oh my god, no!” says Murphy. “It’s the first time he’s cast me in a lead, which I’m still a bit in shock about, but I’m thrilled. It’s a huge part and a lot of work. But in my estimation, you’re working with one of the greatest living directors, so you’re in safe hands.”

As we walk round the lighthouse and make our way back down the pier, he says what he can about Oppenheimer, which, like all Nolan productions, means not a great deal. “The difference with this one is the story is there, everybody knows what happened. But Chris is telling it in a different way, as with Chris you would expect. That’s all I can say.” Is it focused on a particular period of his life? The Manhattan Project, perchance? “I’m not going to say. They’d kill me — they’re so strict!”

Murphy has already begun his research, which will be typically thorough. “There’s a wealth of stuff out there and I will read it all. I am never, ever going to understand quantum mechanics, no matter how hard or how many times people try to explain it to me. There’s 0.0001 per cent of the population on the planet who have the brainpower to understand that. But I can begin to understand, conceptually, what those guys were trying to do.”

It’s another role which, like Tommy Shelby, seems certain to be absorbing and difficult. Later in life, Oppenheimer was openly devastated about his involvement in creating a weapon of mass destruction that killed millions (he was also investigated by the FBI for left-wing leanings and had a tricky love life for good measure). But, as Murphy says when talking about being in Grief is the Thing with Feathers, Enda Walsh’s 2019 stage adaptation of Max Porter’s novel about a bereaved husband, it’s a mode to which he can’t help but be drawn.

“I’ve always been interested in stuff that is — I don’t want to say on the darker side, because that’s too reductive — the melancholic, or the ambiguous, or the more transgressive. That, to me, is drama. That is where the real stuff is to be mined. I’m not interested in romantic comedies. I’m just not. In all the great films or literature or plays, they’re the things I’m interested in. That’s not to say they can’t be funny: Beckett is funny; Enda is very funny. But getting into those knotty, difficult, uncomfortable places — I really find that stimulating.”

Still, doesn’t a role like Oppenheimer, and a project of this magnitude, feel overwhelming? “It does feel immense and it feels terrifying,” he says, as we find ourselves back on the footbridge by the train station. “But if I felt it was easy, I wouldn’t be interested. I do get nervous, anxious and insecure, but then you go, ‘Fuck it. I have been doing it for 25 years and I have done it before. So just keep going.’”

Listening back to the recording later, I realise Murphy is quietly, politely pointing something out to me: that having humility is not the same thing as being out of your depth. I also realise later that, when I’d asked him how come he isn’t more, for lack of a better word, showbizzy, and he’d said, “I don’t know, I’ve never been interested in that stuff. I’ve always been interested in just the work. I’m shit at being anything else other than an actor. I’m shit at being a personality. I’m shit at red carpets. I’m shit at being on talk shows. I’m shit at, like, all the other stuff that comes with it,” that buried in there, he says he’s not shit at being an actor. He might not bang on about it, but Murphy knows his worth.

I had asked Steven Knight if he thought Murphy’s demeanour means people underestimate him. “Maybe they did in the past,” Knight replied. “They don’t anymore.”

We’re at the station now and, though Murphy’s got business at home to attend to — “I’ll take the dog for a big long walk now, because he’ll be at home moaning” — he offers to wait with me for the next train back into the city. We head along the platform to a metal bench, but when we reach it, it’s wet. “Classic Ireland,” says Murphy, not unfondly.

The train’s not for a few minutes, so I ask Murphy how he feels about fame and the way nobody’s normal to you anymore. “It’s a bit weird,” he says. “My kids don’t like it. But it’s how you react to it and how you deal with it. You can deal with it one way or you can deal with it another way… We’ve got a lurker.”

Sure enough, there’s a group of lanky teenage boys on the platform, young men really, all in sportswear, taking the piss out of each other loudly, and one of them is edging closer. I ask Murphy what usually happens in this situation.

“Usually they’ll come up and take a photograph,” he says. “Or surreptitiously take a photograph. I really don’t like that. It’s like the fucking amateur Stasi.”

The man-boy lurker plucks up the courage to approach. Murphy greets him sunnily.

“Hi, man!”

“Are you Cillian Murphy?” says the man-boy (no misidentification there, Martin, take note).

“Yeah,” says Murphy.

“Oh, shit, that’s real cool actually. I saw you walking by and wasn’t sure. That’s real cool.”

“Nice to meet you,” Murphy says.

“You, too,” says the man-boy. “I love your show.”

“Thanks for watching it! The next series will be out in February.”

“February,” says the man-boy. “Nice.”

Murphy turns back to me. “Anything else?”

I scrabble through my notebook. We talk a bit about directors, and the fact that his kids are growing up faster than he’d like, but then my train arrives and, before I know it, I’m standing inside the open doors and we’re semaphoring our goodbyes. The man-boy has backed off, but not far.

“Nice to meet you!” says Murphy as the doors beep. When they’ve closed and the train has started to move, I realise I’m still holding my Dictaphone out to him, and I worry about those boys in the station who’ll be waiting, like a group of dogfish, for him to turn around. I find myself wanting to call out to them, “Don’t hurt him!” like that perfectly sane woman in New York. Then I remember that he’s Cillian fucking Murphy. He’ll be fine.

Story by Miranda Collinge / Source: Esquire.com

Brilliant love that actor he’s a true legend in his own right but mostly I love the fact he is so ‘normal’ lovely insight to this amazing actor and what’s so exciting is he is filming a fab film called small things like these !! In the town I live ! As he says he certainly stays under the radar and enjoys the no shit , no drama around him so it seems . T