On the eve of St. Patrick’s Day, bestselling author, poet, publisher, professor, musician and surfer Lesley Choyce explores Eire’s capital city.

My first visit to Dublin was some time in the 1980s. I had embarked on a ten-day driving tour of the U.K. and Ireland that involved travelling from Heathrow to Cornwall, the coast of Wales, a circumferential foray of Ireland and Northern Ireland, a ferry to Cairnryan, Scotland, and back down to London. It seemed like the thing to do at the time, but it was far too much driving and too little time getting to know the places I visited.

Dublin was on that grand tour, and I recall the ferry docking in Dun Laoghaire and motoring into the capital city with great enthusiasm. My knowledge of Dublin was limited to having been required to read The Dubliners in university, an essay I had written about Jonathan Swift’s time in the city, and the fact that Guinness beer came from here. Eschewing literary pilgrimages because of limited time, I sought out the Guinness brewery, expecting to be welcomed with open arms as a North American fan of the dark Irish brew.

I quickly got lost (as I would many times in Dublin), and discovered I was in a part of town that, in those days, I referred to as “down and out.” As one does on such occasions, I pulled up to a gentleman who was either pondering the sky or loitering to ask directions to the famed brewery. I believe it was the first time I had truly come face to face with a genuine born-and-raised Dubliner.

He was an older man with the traditional Irish tweed cap and somewhat unshaven (but so was I). He walked directly to my car, gripped the halfway rolled down window with two hands and gave me a good look over. I asked if he could direct me to the home of Guinness.

“I could,” he said. “But it will do you no good.” He did not explain at first why it would do me no good.

“So, you’re from America?” he queried.

“Canada,” I corrected, as I would many times again before leaving the Emerald Isle.

“Do you have people here?”

“Not that I know of.”

“Sad, that.” Pause.

He asked a number of questions after that and I answered them as best I could. Then he proceeded to give me what I shall refer to as marital advice. Once he had gotten that off his chest, I asked again about the brewery.

“I’m sorry to disappoint you, but it is currently not open to the public.”

“Why would that be?” I wondered.

He gave me a deeply puzzled look as if I’d asked him for the meaning of life and answered, “I cannot answer that one for you, lad. I’m sorry.”

I bid him good day and he reluctantly let go his grip on the rolled down window of my rental car.

A short drive up the street revealed that I had indeed been circling the Guinness brewery. It was to my memory, an industrial building in a part of town known as St. James Gate. It was rather fortress-like as well, surrounded by a high stone wall with barbed wire on top.

Undaunted, I eventually found an entrance and drove into a loading area where I observed mountains of gleaming kegs.

I asked a workman if there was a brewery tour to be had and he shook his head no and told me I was on private property. And that was the end of that.

I assume much has changed at Guinness since those days since there are now tours and gift shops with beer glasses and tee-shirts and keychains for those who make pilgrimages to St. James Gate.

A second visit to Dublin went somewhat differently. In the spring – a very wet one, I might add – of 1994 I met up with a friend in the waiting lounge of Heathrow Airport. Mike Clugston was a former MacLean’s writer and currently a newspaper editor living in Tokyo. We were to have a kind of reunion by flying on to Dublin and touring about the island. It was a cheerful catch-up of two old chums on the short Aer Lingus flight before we found our rental car and began driving many miles through persistent rain.

Mike, as it turned out, enjoyed walking around old cemeteries in a downpour, but I had less passion for such things. I recall he and I having pointless literary and philosophical arguments in pubs throughout the land. It’s safe to say that we were getting on each other’s nerves as sometimes happens with two intellectuals on longish rainy car trips.

We finally ended up back in Dublin as the rain stopped. Both of us were literary types and so we stayed our first night in a hotel where W.B. Yeats had once taken lodging. I recall parking the car in the basement in a parking space the size of a small refrigerator, jammed up against dozens of other much smaller and much more dented vehicles. Our car was dented as well – street damage from parking at the curb in Lahinch, but I had found a branch in the woods somewhere and jammed it in the trunk in a clever way as to keep the dent pushed out.

The hotel was comfortable enough except that our second story room reeked of car exhaust from the traffic on the busy route below, which I later learned was O’Connell Street, named after the man responsible for “Catholic emancipation” in Ireland.

In the morning we went in search of the James Joyce Museum. I think the sun poked through once or twice and the walking was grand. The museum itself was impressive if you like that sort of thing…and, actually, I do. Here in one glass case was a handwritten page from Ulysses and I reminded myself, I really should try to read that book again.

Over there were other manuscripts. In another case were Mr. Joyce’s glasses, and over in the corner were his pipe and slippers. Old black and white and sepia photographs adorned the walls, but no one looked particularly happy in any of them as if it had been the photographer’s job to say, “Stand over there all together and give us a really sour face, if you would.”

I left there with a classic writer’s fantasy that someday there would be a Lesley Choyce Museum and literary pilgrims would come visit to see a pair of my old sandals, running shoes, perhaps an old surfboard or the pen I used to write my first poem in grade six. Alas.

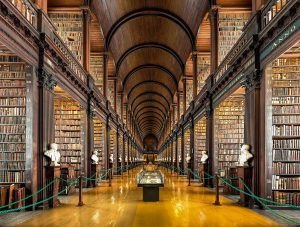

I wanted to find the pub where James Joyce retired each day after penning really long sentences, but Mike had his sights set on the Book of Kells, so we trotted off to Trinity College. There was a long line up at the appropriately named Old Library to see the exhibit. The entry fee seemed rather exorbitant to me at the time, so I went wandering around the lovely campus – all green and sparkling as the rain let up and a renegade shaft of sunlight or two graced my amble.

I knew that Jonathan Swift had attended Trinity in 1682. Later in life he had been appointed dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in 1713, presumably sent there by higher authorities to get him out of England where he had become a political pest with a high caliber writing ability. As I walked and gazed upon delightful architecture, I thought about Swift’s brilliant novel, Gulliver’s Travels and his “Modest Proposal” – a most scathing indictment of the British treatment of the Irish in the eighteenth century. I wondered if there was a monument or grave somewhere in Dublin and would later find his remains in the logical location: St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

I had been invited by a creative writing group at University College Dublin to give a reading from my work and was thrilled to have the opportunity to connect with a young Irish audience. So, later that day, Mike and I checked into a bed and breakfast near the university in a rather tame looking suburban community. Later, I read some of my poems, chatted with the lively group and started to fancy myself as a highly respected author – a kind of straight twentieth century Canadian version of Oscar Wilde (another most famous Irish writer) out on a world tour reading from his work and displaying his intellect to the masses. The thought lingered for at least ten minutes beyond my presentation before it began to fade.

However, one of the organizers of the event had arranged a late-night dinner on my behalf at her parents’ home nearby. Soon, Mike and I found ourselves seated at a large table in a cozy home surrounded by a most lively bunch of older folks from the arts community. There were painters and theatre types, an older actress who I recognized from Irish movies and a few fellow writers. I was told that a neighbour, Maeve Binchy to be exact, had been invited but was out of town on a book tour and sent her apologies. Pity.

Nonetheless, it was a delightful evening, straight out of one of those charming independent Irish Film Board movies that I loved so much, and I soon realized Oscar Wilde had nothing on me. At one point, I noticed that the table was littered with copious empty bottles of wine and I had a hard time convincing Mike we should relent on the witty chatter and make our exit.

The only problem was we didn’t have a clue as to how to find our way back to our accommodation. We discovered that there were far too many cul-de-sacs in this part of town and that somebody should do something about it. It was by sheer perseverance and luck that we found our temporary home and fell asleep after a grand day.

Flash forward if you will to May of 2015 when my wife Linda and I flew into Dublin International to experience our own Irish spring.

To bolster ourselves for urban adventures we first retreated to the Wicklow Mountains to breathe some fresh air and get some rural rest.

We found ourselves hiking around the exotic barren terrain of Wicklow Gap, the unlikely location of the filming of Braveheart. It felt odd to be walking around in the footsteps of Mel Gibson, an Australian actor portraying a Scots warrior here in the Irish countryside.

Once our lungs had been cleansed and prepped for the city, we drove to the River Liffey and found our rented condo high above Sir John Rogersons Quay not far from the Samuel Beckett Bridge. The digs were a bit swanky for my tastes, but had a great view.

Knowing that the Irish had a penchant for naming things after famous writers, I thought perhaps that Sir John Rogerson was a poet or playwright I had not heard of. However, looking him up on Wikipedia I discovered he was a politician and a wealthy man who made

his money as a property developer in the eighteenth century. He was busy getting rich by booting poor Irish families out of tenements and building commercial properties right about the time that Swift was writing Gulliver’s Travels. Bully for him.

The view from the condo prompted me to write a poem that now appears in a book called Climbing Knocknarea. In part the poem reads:

Turn left beyond the Samuel Beckett Bridge

and rise into a glass palace

above the incarcerated Liffey River

looking down at the words “Pig Trap”

spray-painted on the asphalt.

One blue barrel bobbing

on the green-brown tide

as the sun glints off all the polished windows,

the flinty eyes

of this city.

Perhaps I was a bit hard on ole Dublin. A rural lad at heart, I still don’t fully trust cities even though they fascinate me. And Dublin, indeed, is a fascinating place. We walked across the delightfully named Ha’penny Bridge to get a better view of the city. This footbridge was built in 1816 to replace some aging ferries by the ferryman himself, William Walsh, who was granted the privilege of charging pedestrians a half penny to crossing for the next 100 years. I don’t know what the modern equivalent to that would be, but if I held an 1816 ha’penny in my hand today I could sell it to a coin dealer for $75. The citizens of the day found the price “objectionable” but it remained so, even rising to a penny and a half, making it the penny-ha’penny bridge for a while, until the price was lowered to the original in 1919. Readers will be pleased to know that today it’s free.

We made our way to St. Patrick’s Cathedral to pay our respects to Dean Swift and other notable dead folks, and then spent a good hour wandering around St. Stephen’s Green. I couldn’t find anyone who could explain to me who St. Stephen was or why this grand park was named for him. Later, I would learn that he had been appointed by the Apostles to spread Christianity and had given a long speech that angered many listeners which led to him being stoned to death. As a result, he is shown in images down through the centuries with a pile of rocks on his head. And, lo and behold, he is the patron saint of headaches, coffin makers, masons and horses. Who would have guessed?

The park dates back to 1664, and before that it was a marshy area used for grazing sheep. It is finely landscaped and, much to my delight, truly green and bountiful with trees and flowers – all 22 acres of it. It reminded me much of The Public Gardens in Halifax, Nova Scotia making me feel right at home.

There were pubs to be assessed, of course. I can’t say we got to properly know the pubs of Temple Bar or any other section of the fair city, but the names alone tells you that Dublin has a sense of humour. A small sampling of drinking establishments include the following: The Morgue, The Hairy Lemon, The Bleeding Horse, Oil Can Harry’s, Gravediggers, Copper Faced Jacks and, inevitably, the rather British-sounding Cock Tavern. My hope is to make further study of these venerable taverns in a future trip.

I recall getting lost quite often while walking around Dublin, which is a wonderful dilemma.

It seemed that most streets downtown only go a few blocks and then give up, leaving us to weave this way and that trying to find the river which would lead us back to our condo. It doesn’t help that if you do find a street, it changes names every few blocks. Hence, Woody Essex Quay turns to Wellington Quay, then Aston Quay, then Burgh Quay, Georges Quay, City Quay and, finally, the familiar Sir John R. Quay.

After we checked out of our apartment, I discovered that a rubber door stop had somehow found its way into my suitcase. I assure you this was an accident and not theft.

Nonetheless, it led to us getting a bad review as renters posted on the Airbnb site, which, as things go on the internet, will most likely remain posted until the end of time, probably barring us from renting accommodations hereafter in many parts of the English-speaking world.

As we were departing the city to head off to Sligo, we encountered a detour on Dame Street soon after it had changed from being College Green Street. The orange detour signs took us hither and yon. Eventually, it seemed, the detour sign people had given up – gone off for a drink at the Hairy Lemon, perhaps – and there were no more signs, leaving us to ping pong around parts of town we were not much interested in. Curiously enough, we eventually came upon the Guinness brewery ,which is now a world tourist destination called The Guinness Storehouse charging as much as 55 Euros (about $75) for a 1½ hour-tour with a couple of pints thrown in, I would imagine.

But for us, the West Coast of Ireland awaited.

Leave a Comment