Celtic music is a broad grouping of musical genres that evolved out of the folk musical traditions of the Celtic peoples of Western Europe. The term Celtic music may refer to both orally-transmitted traditional music and recorded popular music with only a superficial resemblance to folk styles of the Celtic peoples.

Most typically, the term Celtic music is applied to the music of Ireland and Scotland, because both places have produced well-known distinctive styles which actually have genuine commonality and clear mutual influences. The music of Wales, Cornwall, Isle of Man, Brittany, Northumbria and Galicia are also frequently considered a part of Celtic music, the Celtic tradition being particularly strong in Brittany, where Celtic festivals large and small take place throughout the year. Finally, the music of ethnically Celtic peoples abroad are also considered, especially in Canada and the United States.

The most significant impact of Celtic Music on American styles, however, is undoubtedly that on the evolution of country music, a style which blends Anglo-Celtic traditions with “sacred hymns and African American spirituals”. Country music’s roots come from “Americanized interpretations of English, Scottish, Scots and Scots-Irish traditional music, shaped by African American rhythms, and containing vestiges of (19th century) popular song, especially (minstrel songs)”. This fusion of Anglo-Celtic and African elements “usually consisted of unaccompanied solo vocals sung in a high-pitched nasal voice, the lyrics set to simple melodies (and using) ornamentation to embellish the melody”; this style bears some similarities to the traditional song form of sean-nós, which is similarly highly-ornamented and unaccompanied.

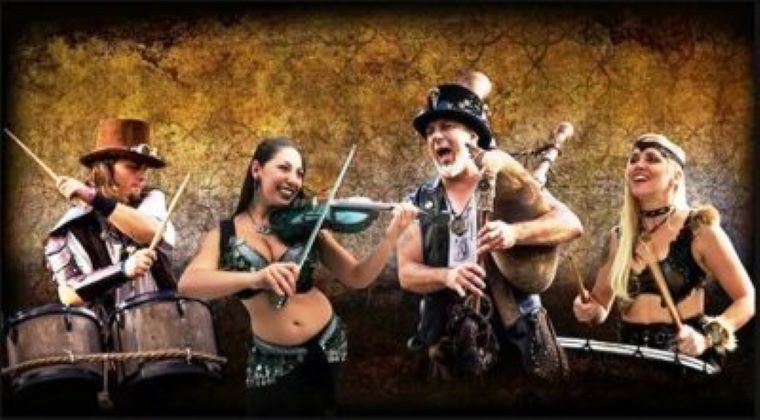

Celtic-Americans have also been influential in the creation of Celtic Fusion, a set of genres which combine traditional Celtic music with contemporary influences.

Irish American Music

Irish emigrés created a large number of emigrant ballads once in the United States. These were usually “sad laments, steeped in nostalgia, and self-pity, and singing the praises… of their native soil while bitterly condemning the land of the stranger”. These songs include famous songs like “Thousands Are Sailing to America” and “By the Hush”, though “Shamrock Shore” may be the most well-known in the field.

Francis O’Neill was a Chicago police chief who collected the single largest collection of Irish traditional music ever published. He was a flautist, fiddler and piper who was part of a vibrant Irish community in Chicago at the time, one that included some forty thousand people, including musicians from “all thirty-two counties of Ireland”, according to Nicholas Carolan, who referred to O’Neill as “the greatest individual influence on the evolution of Irish traditional dance music in the twentieth century”.

In the 1890s, Irish music entered a “golden age”, centered on the vibrant scene in New York City. This produced legendary fiddlers like James Morrison and Michael Coleman, and a number of popular dance bands that played pop standards and dances like the foxtrot and quicksteps; these bands slowly grew larger, adding brass and reed instruments in a big band style [6]. Though this golden age ended by the Great Depression, the 1950s saw a flowering of Irish music, aided by the foundation of the City Center Ballroom in New York. It was later joined by a roots revival in Ireland and the foundation of Mick Moloney’s Green Fields of America, an organization that promotes Irish music.

Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is internationally known for its traditional music, which has remained vibrant throughout the 20th century, when many other traditional forms worldwide lost popularity to pop music. In spite of emigration and a well-developed connection to music imported from Britain and the United States, Irish music has kept many of its traditional aspects; indeed, it has itself influenced many forms of music, such as country and roots music in the USA, which in turn have greatly influenced rock music in the 20th century. It has occasionally also been modernised, however, and fused with rock and roll, punk rock and other genres. Some of these fusion artists have attained mainstream success, at home and abroad. (One example of a traditional song that has received exposure as the result of being recorded by pop and rock artists is “She Moved Through the Fair”.)

During the 1970s and 1980s, the distinction between traditional and rock musicians became blurred, with many individuals regularly crossing over between these styles of playing as a matter of course. This trend can be seen more recently in the work of bands and individuals like U2, Horslips, Clannad, The Cranberries, The Corrs, Van Morrison, Thin Lizzy, Sinéad O’Connor, My Bloody Valentine, Rory Gallagher, and The Pogues.

Nevertheless, Irish music has shown an immense inflation of popularity with many attempting to return to their roots. There are also contemporary music groups that stick closer to a traditional sound, including Altan, Gaelic Storm, Déanta, Lúnasa, Kila and Solas. Others incorporate multiple cultures in a fusion of style, such as Afro Celt Sound System and Loreena McKennitt.

In addition to folk music, Ireland also has a rich store of contemporary classical music.

Irish traditional music, like all traditional music, is characterized by slow-moving change, which usually occurs along accepted principles. Songs and tunes believed to be ancient in origin are respected. It is, however, difficult or impossible to know the age of most tunes due to their tremendous variation across Ireland and through the years; some generalization is possible, however — for example, only modern songs are written in English, with few exceptions, the rest being in Irish. Most of the oldest songs, tunes, and methods are rural in origin, though more modern songs and tunes often come from cities and towns.

Music and lyrics are passed aurally/orally, and were rarely written down until recently (depending upon your definition of “recently”, there are many examples of written music previous to 1800). Of major importance to the transcribing of melodies belonging to both the instrumental traditions and the song traditions were the collectors. These included Petrie, Bunting, O’Neill and many others. Though solo performance is preferred in the folk tradition, bands or at least small ensembles have probably always been a part of Irish music since at least the mid-19th century, although this is a point of much contention among ethnomusicologists.

For instance, guitars and bouzoukis only entered the traditional Irish music world in the late 1960s. The bodhrán, once known in Ireland as a tambourine, is first mentioned in the nineteenth century. Ceili bands of the 1940s often included a drum set and stand-up bass as well as saxophones. (The band At The Racket continues the “tradition” of the saxophone in Irish music.) As of current writing, the first three instruments are now generally accepted in traditional Irish music circles (although perhaps not in the most purist of venues), while the latter three are generally not. (The Pogues received much criticism for their use of a drum kit, for instance.)

Furthermore, such “unimpeachable” instruments as button accordion and concertina made their appearances in Irish traditional music only late in the nineteenth century. There is little evidence for the flute having played much part in traditional music before art musicians abandoned the wooden simple-system instrument still preferred by trad fluters for the Boehm-system of the modern orchestra, and the tin whistle is another mass-produced product of the Industrial Revolution. A good case can be made that the Irish traditional music of the year 2005 has much more in common with that of the year 1905 than that of the year 1905 had in common with the music of the year 1805.

More recently, traditional Irish music has been “expanded” to include new styles, arrangements, and variations performed by bands, although arguments run rife as to whether you may then call this music “traditional.” However, the greater part of the community has accepted that the music played by such bands as Planxty and the Bothy Band and their numerous spiritual descendants is indeed traditional.

Musicians from non-Irish styles (bluegrass, oldtime, folk) have discovered the appeal of Irish traditional music. However, the rhythmic pulse and melodic flow of Irish traditional music are quite distinct to the rhythmic and melodic structures that govern other musical forms, even in the case of the few tunes shared between these musical genres. Also, Irish sessions and bluegrass and old time jams carry completely different sets of etiquette and expectations, and these do not, for the most part, integrate well; this has led to many misunderstandings and outright confrontations.

Due to the importance placed on the melody in Irish music, harmony should be kept simple (although, fitting with the melodic structure of most Irish tunes, this usually does not mean a “basic” I-IV-V chord progression), and instruments are played in strict unison, always following the leading player. True counterpoint is mostly unknown to traditional music, although a form of improvised “countermelody” is often used in the accompaniments of bouzouki and guitar players. Structural units are symmetrical and include decorations, in many cases imaginative and elaborate, of the rhythm, text, melody and phrasing, though not usually of dynamics.

Unaccompanied vocals ar sean nós (“in the old style”) are considered the ultimate expression of traditional singing, usually performed solo, but sometimes as a duet. Sean nós singing is highly ornamented and the voice is placed towards the top of the range; to the first-time listener, accustomed to pop and classical singers, sean nós often sounds more “Arabic” or “Indian” than “Western”. A true sean nós singer will vary the melody of every verse, but not to the point of interfering with the words, which are considered to have as much importance as the melody. Non-sean nós traditional singing, even when accompaniment is used, uses patterns of ornamentation and melodic freedom derived from sean nós, and, generally, a similar voice placement.

The concept of ‘style’ is of large importance to Irish traditional musicians. At the start of the last century, distinct variation in regional styles of performance existed. With increased communications and travel opportunities, regional styles have become more standardized, with soloists aiming now to create their own, unique, distinctive style, often hybrids of whatever other influences the musician has chosen to include within their style.

Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is internationally known for its traditional music, which has remained vibrant throughout the 20th century, when many traditional forms worldwide lost popularity to pop music. In spite of emigration and a well-developed connection to music imported from the rest of Europe and the United States, the music of Scotland has kept many of its traditional aspects; indeed, it has itself influenced many forms of music.

Scottish traditional music, although influencing and being influenced by both Irish traditional music and English traditional music, is very much a creature unto itself, and, despite the popularity of various international pop music forms, remains a vital and living tradition. As of 2003, there are several Scottish record labels, music festival and a roots magazine, Living Tradition.

Many outsiders associate Scottish folk music almost entirely with bagpipes, which has indeed long played an important part of Scottish music. It is, however, not unique or indigenous to Scotland, having been imported around the 15th century and still being in use across Europe and farther abroad. The pìob mór, or Highland bagpipe, is the most distinctively Scottish form of the instrument; it was created for clan pipers to be used for various, often military or marching, purposes. Piping clans included the MacArthurs, MacDonalds, McKays and, especially, the MacCrimmons, who were hereditary pipers to the Clan MacLeod.

Folk and Ceilidh Music takes many forms in a broad musical tradition, although the dividing lines are not rigid, and many artists work across the boundaries. Culturally there is a split between the Gaelic tradition and the Scots tradition.

There are ballads and laments, generally sung by a lone singer with backing, or played on traditional instruments such as harp, fiddle, accordion or bagpipes.

Dance music is played across Scotland at dances or ceilidhs. Group dances such as jigs, strathspeys, waltzes and reels, are performed to music provided typically by an ensemble, or dance band, which can include fiddle (violin), bagpipe, accordion and percussion. The major names to know in this part of the musical tradition are Niel Gow, James Scott Skinner, and Jimmy Shand.

There are traditional folk songs, which are generally melodic, haunting or rousing. These are often very region specific, and are performed today by a burgeoning variety of folk groups. Most famous of which is Capercaillie.

Popular songs were originally produced by Music Hall performers such as Harry Lauder and Will Fyffe for the stage. More modern exponents of the style have included Andy Stewart, Glen Daly, Moira Anderson, Kenneth McKellar and the Alexander Brothers.

Military music, typically massed pipes and drums. Major Scottish regiments maintain bapipe and drum bands which preserve scottish marches, quicksteps, reels and laments. Many towns also have voluntary pipe bands which cover the same repertoire.

Though bagpipes are closely associated with Scotland and only Scotland by many outsiders, the instrument (or, more precisely, family of instruments) is found throughout large swathes of Europe, North Africa and South Asia. Out of the many varieties of Scottish bagpipes, the most common in modern days is the Highlands variety, which was spread through its use by the Highland regiments of the British Army.

The most traditional form of Highland bagpipe music is called pibroch, which consists of a theme (urlar) which is repeated, growing increasingly complex each time. The last, and most complex variation (cruunluath), gives way to a sudden and unadorned rendition of the theme.

Bagpipe competitions are now common in Scotland, with popular bands including colonial groups like the Victoria Police Pipe Band (Australia) and Canada’s 78th Fraser Highlanders Pipe Band and the Simon Fraser University Pipe Band, as well as Scottish bands like Shotts and Dykehead Pipe Band and Strathclyde Police Pipe Band.

Scottish traditional fiddling encompasses a number of regional styles, including the bagpipe-inflected west Highlands, the upbeat and lively style of Norse-influenced Shetland Islands and the strathspeys and slow airs of the North-East. The instrument arrived late in the 17th century, and is first mentioned in 1680 in a document from Newbattle Abbey in Midlothian, Lessones For Ye Violin.

In the 18th century, Scottish fiddling is said to have reached new heights. Fiddlers like William Marshall and Niel Gow were legends across Scotland, and the first collections of fiddle tunes were published in midcentury. The most famous and useful of these collections was a series published by Nathaniel Gow, one of Niel’s sons, and a fine fiddler and composer in his own right. Classical composers such as Charles McLean, James Oswald and William McGibbon used Scottish fiddling traditions in their Baroque compositions.

Scottish fiddling is the root of much American folk music, such as Appalachian fiddling, but is most directly represented in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, an island on the east coast of Canada, which received some 25,000 emigrants from the Scottish Highlands during the Highland Clearances of 1780-1850. Cape Breton musicians such as Natalie MacMaster, Ashley MacIsaac, and Jerry Holland have brought their music to a worldwide audience, building on the traditions of master fiddlers such as Buddy MacMaster, Carl MacKenzie and Winston Scotty Fitzgerald.

Among native Scots, Alasdair Fraser and Aly Bain are two of the most accomplished, following in the footsteps of influential 20th century players such as James Scott Skinner, Hector MacAndrew, Angus Grant and Tom Anderson. The growing number of young professional Scottish fiddlers makes a complete list impossible. Top current names include Aidan O’Rourke, Bruce MacGregor, Catriona MacDonald, members of the band Blazin Fiddles; John McCusker; Duncan Chisholm of Wolfstone; Chris Stout of the Shetland group Fiddlers Bid; Pete Clark, Eilidh Shaw, Gavin Marwick, Anna-Wendy Stevenson, Angus Grant Jr., and Alasdair White.

Breton

Breton

Traditional Breton folk music includes a variety of vocal and instrumental styles. Purely traditional musicians became the heroes of the roots revival in the XXth century, most importantly the Goadec sisters. At the end of the XIXth century, the vicomte Theodore Hersart de la Villemarqué’s collection of largely nationalistic Breton songs, Barzaz Breiz, was also influential, and was partially responsible for continuing Breton traditions.

Undoubtedly the most famous name in modern Breton music is Alan Stivell, who popularized the Celtic harp with a series of albums in the early 1970s, including most famously Renaissance de la Harpe Celtique (1971) and Chemins de Terre (1973). His harp was built by his father, who based it off the plans for the medieval Irish Brian Boru harp; this type was unknown in Brittany before Stivell. He later began playing the bombarde, a double-reeded shawm (or oboe), and began recording Breton folk, Celtic harp and other Celtic music, mixing influences from American rock and roll. Stivell’s most important contribution to the Breton music scene, however, has probably been his importation of rock and other American styles, as well as the formation of the idea of a Breton traditional band.

Inspired by Stivell, bands like Kornog and Gwerz arose, adapting elements of the Irish and Scottish Celtic music scene.

The most famous band of Breton music is Tri Yann, from Nantes (their original name is Tri Yann an Naoned, litteraly “the three John from Nantes”). It was born in 1972 and still famous, claiming it produces a progressive rock-folk-celto-medieval music ! It gave some musical gems, now standards, like “Les filles des Forges”, “Les prisons de Nantes”, “La Jument de Michao”, “Pelot d’Hennebont”, and new interpretation of Irish music, like “Cad é sin don té sin”, “Si mort a mors” (originally An Cailín Rua), “La ville que j’ai tant aimée” (from “The town I loved so well”), “Mrs McDermott” (from the XVIIth-century Irish harpist Ó Carolan), “Kalonkadour” (from “Planxty Irwin”).

Another famous band is Soldat Louis, from Lorient. More rock-oriented, it plays modern compositions talking about Brittany and the life on the sea (“Du rhum, des femmes”, “Martiniquaise”, “Pavillon noir”).

Besides folk-rock, recent groups have included world music influences into their repertoires – especially younger groups such as Wig-a-Wag. Hip hop with a Celtic flavour has been espoused by groups such as Manau.

Brittany hosts annual rock and pop festivals, the biggest in Brittany, also in France, being the Festival des Vieilles Charrues (held in late July in Carhaix, Finistère), the Route du Rock (mid-August, Saint-Malo) and the Transmusicales of Rennes, held in early December.

Newfoundland

There are very strong connections between Newfoundland folk music and Irish music, however elements of English folk music and French-Canadian music can be heard within the style.

It should be noted that a very traditional strain of Irish music exists in Newfoundland, especially in the primarily Irish-Catholic communities along the southern shore.

The instrumentation in Newfoundland music includes the button accordion, guitar, violin, tin whistle and more recently the bodhrán. Many Newfoundland traditional bands also include bass guitar and drum kit. Other folk instruments such as the mandolin and bouzouki are common especially among Newfoundland bands with an Irish leaning.

Because Newfoundland is an island in the North Atlantic, many of the songs focus on the fishery and seafaring. Many songs chronicle the history of this unique people. Instrumental tune styles include jigs, reels, two steps, and polkas.

Nova Scotia

Music is a part of the warp and weft of the fabric of Nova Scotia’s cultural life. This deep and lasting love of music is expressed the through the performance and enjoyment of all types and genres of music. While popular music In Nova Scotia has experienced almost two decade of explosive growth and success, the province remains best known for its folk and traditional based music.

Nova Scotia’s folk music is characteristically Scottish in character, and traditions from Scotland are kept very traditional in form, in some cases more so than in Scotland. This is especially true of the island of Cape Breton, one of the major international centers for Celtic music.

Despite the small population of the province, Nova Scotia’s music and culture is influenced by several well established cultural groups, that are sometimes referred to as the “Founding Cultures.”

Originally populated by the Mi’kmaq First Nation, the first European settlers were the French, who founded Acadia in 1604. Nova Scotia was briefly colonized by Scottish settlers in 1620, though by 1624 the Scottish settlers had been removed by treaty and the area turned over French settlement until the mid-1700s. After the defeat of the French and prior expulsion of the Acadians, settlers of English, Irish, Scottish and African decent began arriving on the shores of Nova Scotia.

Settlement greatly accelerated by the resettlement of Loyalists to Nova Scotia during the period following the end of the American revolutionary war Nova Scotia is one of three Canadian Maritime Provinces, or simply, The Maritimes. When combined with Newfoundland and Labrador the region is known as the Atlantic Provinces, or Atlantic Canada. . It was during this time that a large African Nova Scotian community took root, populated by freed slaves and Loyalist blacks and their families, who had fought for the crown in exchange for land. This community later grew when the Royal Navy began intercepting slave ships destined for the United States, and deposited these free slaves on the shores of Nova Scotia.

Later, in the 1800s the Irish Famine and Scottish Highland Clearances resulted in large influxes of migrants with celtic cultural roots, which helped to define the dominantly celtic character of Cape Breton and the north mainland of the province. This celtic, or gaelic culture was so pervasive that at the outset of World War II reporters from London, England were horrified when some of the first regiments to arrive in England from Canada piped themselves ashore, styled themselves as “Highland Regiments” and spoke Scots Gaelic as their primary language.

Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a region in the southwest United Kingdom which has been historically Celtic, though Celtic-derived traditions had been moribund for some time before being revived during a late 20th century roots revival.

The most famous modern Cornish folk performer is likely the Cornish-Breton family band Anao Atao; other well-known musicians include the singer Brenda Wootton. The 1980s band Bucca is recognized as a major pioneer in the popularization of Cornish music.

The town of Cadgwith (on the Lizard Peninsula) is known for an informal, weekly gathering of singers; their material includes a number of common folk songs, as well as their anthem “The Robbers Retreat”. The Camborne Town Band is a long-renowned band, formed in 1841 in a tin mining town. It has been estimated that there are over 100 bands playing mostly or exclusively cornish tunes in cornwall at present. As the traditional music corpus is not as large in some other countries (though still a great number of tunes) many bands will fill some specific niche in the style, giving great variation in an event.

The Cornwall Folk Festival has been held annually for more than three decades. Other notable festivals are the pan-celtic lowender perran and midsummer festival golowan. Numerous other festivals and annual events have a cornish music theme.

Cornwall has won the PanCeltic Song Contest three years in a row between 2003 and 2005.

Cornish musicians have used a variety of traditional Celtic instruments, as well as imported mandolins, banjos and accordions. The bodhrán (crowdy crawn in Cornish) has remained especially popular for years. Old inscriptions and carvings in Cornwall (such as at Altarnun church at Bodmin moor) indicate that a line-up at that time might include an early fiddle (crowd), bombarde, bagpipes and harp.

Folk songs include “Sweet Nightingale”.

Cornish dance music is especially known for the cushion dance from the 19th century, which was based on an old tune adapted for French court dances. The cushion dance was originally an aristocratic past-time, that eventually crossed over to the poor. The dance’s popularity peaked in the early 1820s.

Cornish music festivals called troyl were common, and are analogous to the closely-related fest-noz of the Bretons.

In the later part of the 20th century, the temperance movement became a major part of Cornish culture. Along with it came choral traditions; many folk songs were adapted for carolling, hymnal singing. Eventually, processional bands appeared, leaving behind a legacy of marches and polkas.

Sport has also been an outlet for many Cornish folktunes, and Trelawney in particular has been taken up as a kind of unofficial national anthem by Cornish rugby fans.

Isle of Mann

The Isle of Man is a small island nation in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. Its culture is Celtic in origin, influenced historically by its neighbours, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. The island is not part of the United Kingdom, but Manx music has been strongly affected by English folk song as well as British popular music.

A roots revival of Manx folk music began late in the 20th century, alongside a general revival of the Manx language and culture. The 1970s revival was kickstarted, after the 1974 death of the last native speaker of Manx, by a music festival called Yn Chruinnaght in Ramsey.

Prominent musicians of the Manx musical revival include Emma Christian (Ta’N Dooid Cheet – Beneath the Twilight), whose music includes the harp and tin whistle, and harpist and producer Charles Guard (Avenging and Bright), an administrator at the Manx Heritage Foundation, MacTullagh Vannin (MacTullagh Vannin) and the duo Kiaull Manninagh (Kiaull Manninagh). Modern bands include The Mollag Band and Paitchyn Vannin.

Galicia

In recent times, however, many Galician folk musicians have considered Galician music to be at least partially “Celtic” in origin, and whether or not this is the case much modern Galician folk and folk-rock is strongly influenced by Irish and Scottish traditions. Certainly, Galicia is nowadays a strong player on the international Celtic folk scene; and as a result, elements of the pre-industrial Galician tradition have become integrated into the modern Celtic folk repertoire and style. Many, however, claim that the “Celtic” appellation is merely a marketing tag, such as Susana Seivane, a Galician gaiteira, who said “I think (the ‘Celtic’ moniker is) a label, to sell more. What we do is Galician music”. In any case, due to the “Celtic” brand, the Galician music industry is the only non-Spanish speaking music in Spain that has an audience beyond the country’s borders.

The ancestors of the Celts lived in Spain after about 600 BC, arriving from the area around the upper Danube and Rhine rivers. Little is known about the population that existed there before then. During the 1st century, the Roman Empire conquered all of modern Spain and Portugal. The Latin language came to dominate the region, and is the ancestor of all the Romance languages of the Iberian Peninsula (Galician, Portuguese, Catalan and Spanish). With the exception of Basque, all the other regional languages died out. The departure of the Romans in the 5th century led to the invasion by the Germanic Suevi people in the northwest, who left little cultural impact. By the 8th century, the Moors controlled southern Iberia, but never conquered the north, which was the Kingdom of Asturias.

In 810, it was claimed that the remains of Saint James, one of the apostles, had been found in Galicia. The site, which soon became known as Santiago de Compostela, was the premier pilgrimage destination in the European Middle Ages and served as a rallying point for Christians to defend the area against the Moors. This had a monumental effect on the folk culture of the area, as the pilgrims brought with them elements, including musical instruments and styles, from as far afield as Scandinavia.

However, little is known about musical traditions from this era. A few manuscripts are known, such as those by the 13th century poet and musician Martín Codax, which indicate that some distinctive elements of modern music, such as the bagpipes, were common by then.

The Galician folk revival drew on early 20th century performers like Perfecto Feijoo, a gateiro and hurdy-gurdy player. The first commercial recording of Galician music had come in 1904, by a corale called Aires d’a Terra from Pontevedra. The middle of the century saw the rise of Ricardo Portela, who inspired many of the revivalist’s performers, and played in influential bands like Milladoiro.

During the regime of Francisco Franco, Galician folk music was suppressed, or forced to adopt lyrics with little for most listeners to connect to. Honest displays of folk life were replaced with rehearsed spectacles of patriotism, leading to a decline in popularity for traditional styles. The appropriation and sanitization of folk culture for the authorities led to a perception that folk music was folklorico. In the late 1970s, recordings of Galician gaita began in earnest following the death of Franco in 1975, as well as the Festival Internacional Do Mundo Celta (1977), which helped establish some Galician bands. Aspiring performers began working with bands like Os Areeiras, Os Rosales, Os Campaneiros and Os Irmáns Graceiras, learning the folk styles; others went to the renowned workshop of Antón Corral at the Universidade Popular de Vigo. Some of these musicians then formed their own bands, like Milladoiro.

In the 1980s, some famous performers began to emerge from the Galician (and Asturian) music scene. The included Uxía, a singer originally with the band Na Lúa, whose 1995 album Estou Vivindo No Ceo and a subsequent collaboration with Sudanese singer Rasha, gained her an international following.

It was Carlos Nuñez, however, who has done the most to popularize Galician traditions. His 1996 A Irmandade Das Estrelas sold more than 100,000 copies and saw major media buzz, partially due to the collaboration with well-known foreign musicians like La Vieja Trova Santiaguera, The Chieftains and Ry Cooder. His follow-up, Os Amores Libres, included more fusions with flamenco, Celtic music (especially Breton) and Berber music.

Other modern Galician gaiteru include Xosé Manuel Bundiño and Susana Seivane. Seivane is especially notable as the first major female gaiteiras, paving the way for many more women in the previously male-dominated field. Galicia’s most popular singers are also mostly female, including Uxía, Mari Luz Cristóbal Caunedo, Sonia Lebedynski and Mercedes Peón.

Wales

Wales is a part of the United Kingdom, but a culturally distinct Celtic country. Its traditional music is related to the Celtic music of countries such as Ireland and Scotland. Welsh folk music has distinctive instrumentation and song types, and is often heard at a twmpath (folk dance session), gŵyl werin (folk festival) or noson lawen (traditional party or ceilidh). Modern Welsh folk musicians have sometimes had to reconstruct traditions which had been suppressed or forgotten, as well as compete with imported and indigenous rock and pop trends. The record label Fflach Tradd has become especially influential. There is also a thriving modern musical scene which spans several genres and two languages.

Welsh folk is known for a variety of instrumental and vocal styles, as well as more recent singer-songwriters drawing on folk traditions. The most traditional of Welsh instruments is the harp. The triple harp (telyn deires, “three-row harp”) is a particularly distinctive tradition: it has three rows of strings, with every semitone separately represented, while modern concert harps use a pedal system to change key by stopping the relevant strings. It has been popularised through the efforts of Nansi Richards, Llio Rhydderch and Robin Huw Bowen. Another distinctive instrument is the crwth, which, superseded by the fiddle, lingered on later in Wales than elsewhere but died out by the nineteenth century at the latest.

The fiddle is an integral part of Welsh folk music. Among its modern exponents are The Kilbrides from Cardiff, who play mostly in the South Welsh tradition but also perform tunes from throughout the British Isles.

This piece is exceptionally well researched and written. Eschewing any pretense at high-brow scholarship, the text is articulate and the style is accessible, well-tuned and an easy read. Go raibh míle maith agaibh.