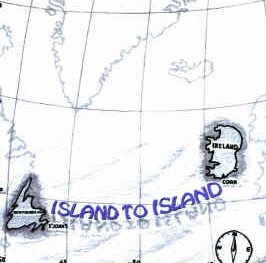

As the puffin flies, it is 3,163 kilometers (1,965 miles) from the very westernmost tip of Donegal to the extreme eastern edge of Newfoundland.

As I have written previously, Newfoundland is the land of my mother’s family; both of my grandparents were born and bred on “The Rock.” My grandmother, Caroline Dunphy, is of Irish stock, with roots from Kerry to Derry. My grandfather, Stan Smart, was also a proud and devout Irish Catholic, though his ancestry remains unclear.

To that end, I have connected with several genealogists in recent weeks to unravel that mystery. There are conflicting ideas as to the Smart family’s origins, and more will be revealed in the days and weeks ahead.

While my grandfather’s link to Eire (Donegal, specifically) remains uncertain, there is no doubting the connections between “ye’ old country” and the New World.

For starters, both are islands, each awash in a spirit of resiliency and independence.

Interestingly, geologists now believe that, millions of years ago, Ireland and Newfoundland were once joined. In fact, if pushed together, the two land masses fit like puzzle pieces.

Interestingly, geologists now believe that, millions of years ago, Ireland and Newfoundland were once joined. In fact, if pushed together, the two land masses fit like puzzle pieces.

As such, much of the topography is alike; rugged hills and valleys, craggy coastlines, glacial divides, sub-strata and so forth are similar. Likewise, the top-soil, flora and fauna share commonalities, as does the dampish climate for much of the year. To that end, agricultural opportunities would be familiar for settlers, as would those for aquaculture.

It is easy to understand the appeal for long-ago Irish emigrants looking to build a new life for themselves; Newfoundland was, for many, a “home-away-from-home.”

The first documented voyage between the two countries (Newfoundland did not join Canada until 1949) was in 1536, when the sea vessel Mighel returned to Cork carrying fish stock. The next recorded trip was in 1608. After that, traffic lanes became busier.

According to Wikipedia, “Beginning around 1670, and particularly between 1750 and 1830, Newfoundland received large numbers of Irish immigrants. These migrations were seasonal or temporary. Most Irish migrants were young men working on contract for English merchants and planters. It was a substantial migration, peaking in the 1770s and 1780s when more than 100 ships and 5,000 men cleared Irish ports for the fishery.

“Virtually from its inception, a small number of young Irish women joined the migration. Many stayed and married overwintering Irish male migrants. Seasonal and temporary migrations slowly evolved into emigration and the formation of permanent Irish family settlement in Newfoundland. An increase in Irish immigration, particularly of women, between 1800 and 1835, and the related natural population growth, helped transform the social, demographic, and cultural character of Newfoundland.

In 1836, a Newfoundland government census listed more than 400 settlements. The Irish, and their offspring, composed half of the total population. Close to three-quarters of them lived in St. John’s and nearby, in an area still known as the Irish Shore.”

Today, the Irish influence in Newfoundland remains strong, with 21.5 per cent of the population claiming ancestry from the Emerald Isle. You will hear it in the language and in the accent across the island, and in the fiddles and bodhrans in homes and pubs. You will read it in the literature, where the custom of traditional storytelling continues. You will taste it in the cuisine, where the Jiggs Dinner (salt beef, boiled together with potatoes, carrot, cabbage, and turnip) will keep you nourished. You will see it in the art and architecture and in the Aran-esque sweaters worn by almost everyone. In some areas you can still smell the Irish turf burning.

Today, the Irish influence in Newfoundland remains strong, with 21.5 per cent of the population claiming ancestry from the Emerald Isle. You will hear it in the language and in the accent across the island, and in the fiddles and bodhrans in homes and pubs. You will read it in the literature, where the custom of traditional storytelling continues. You will taste it in the cuisine, where the Jiggs Dinner (salt beef, boiled together with potatoes, carrot, cabbage, and turnip) will keep you nourished. You will see it in the art and architecture and in the Aran-esque sweaters worn by almost everyone. In some areas you can still smell the Irish turf burning.

Like Ellis Island, St. John’s – Newfoundland’s colourful capital – was a gateway for the Irish into North America. And while many of Eire’s emigrants chose to embed themselves on “The Rock,” many more used it as a springboard to build new and better lives for themselves across Canada, in places like Halifax, Charlottetown, Fredericton, Quebec City, Ottawa, Toronto, Winnipeg, Regina, Calgary, Vancouver, and – in my case – Montreal.

And – like the Black Thorn and Black Sally trees that dot the landscape in Donegal, forever swaying eastward from the strong westerly winds – there are millions of Irish-Canadians, like me, with a deep and natural leaning to come home.

The time has come when I must go, I’ll bid you all adieu

The open highway calls to me to do the things I do

And when I’m wandering far away, I’ll hear your voices call

And please God I’ll soon return unto the homes of Donegal…

Stephen Patrick Clare

January 21, 2019

Leave a Comment