It is upon the treeless hills of windswept Shetland and the vast, snow-covered plains of the Canadian arctic that Shona Main feels closest to the spirit of pioneering Scottish filmmaker, Jenny Brown Gilbertson.

“These are the landscapes where Jenny lived and made her documentary films,” explains Main, a law school graduate turned filmmaker. “After studying her work in Shetland, I felt that I had to follow her to the arctic.”

Main is now back in Shetland, painstakingly editing film from the four months she spent in the arctic communities of Coral Harbour, in Nunavut’s Kivalliq region, and Grise Fiord, on Ellesmere Island. It is there that Gilbertson, who died in Shetland in 1990, lived and filmed for nine years.

Gilbertson’s work is the subject of Main’s PhD thesis at Stirling University and Glasgow School of Art. More than 20 of Gilbertson’s completed films are housed in the Shetland Museum, the Scottish Screen Archives, the British Film Institute and the Canadian Museum of History.

“Jenny’s distinctive work and her methods require more attention than she has had to date,” shares Main, who lives in Dundee when she is not working in Shetland. “I am sure that she has not been given her proper place in history,”

Throughout the 1930s, Gilbertson was making films in the most northernly part of Great Britain. Born in 1902, she stood less than five feet tall, the only daughter in a well-to-do family in Glasgow. She insisted on going to university, making it clear that the life of a society matron was not for her. Instead she went to London to study journalism before buying her first 16 mm camera.

Camera in hand, she decided that Shetland – which she had visited years earlier – would be the scene of her first film.

“It was a very unusual occupation for a single woman in those times.”

“It was Jenny’s way, even from the first, to go and live amongst the people she wanted to film, to get to know them and to use what she learned in her work. She was never one to sweep in, take what she needed and be off.”

In 1931, Gilbertson made her way to Shetland – which is still today a 12-hour ferry ride from Aberdeen on the Scottish mainland. Determined to make a film about a crofting family she had met previously, she set about learning the crofter’s life; herding livestock, cutting peat, and harvesting from the sea.

“She captured the men at work but also filmed women churning butter, cooking potatoes and by the fire knitting fair isle sweaters.”

In the course of her early work she met Johnny Gilbertson, a young crofter who introduced her to other families, helped set up her shots and acted in them as required. The young couple were soon married.

“She told us she was with a group of women cleaning fish and was up to her elbows in fish guts when she first met him,” recalls granddaughter Heather Tulloch, who lives in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia.

Gilbertson invited Scottish documentary maker John Grierson to view her first film, A Crofter’s Life in Shetland. Impressed, he arranged for it to premiere in Edinburgh, advised her to get a better camera and then purchased her next five films.

Together with her husband, Gilbertson toured a subsequent film, Rugged Island, across Britain and Canada. When a daughter was born, space was made for her amongst the reels of film in their car and they resumed touring Britain. She continued filming through the birth of a second daughter. Upon the advent of the Second World War,

Johnny Gilbertson joined the Royal Army Service Corps. Injured from combat, Johnny came home and ran a small store with his wife until she took a job as a teacher, a temporary position that turned into a 20-year career. It was not until 1967, when she retired from teaching and after her husband died suddenly, that she began filming again.

“She was quite lost without my grandfather,” says Tulloch. “It was only when a relative suggested that she dig-out her camera and get some shots of a particularly stormy sea that her love of photography seemed to come back to her.”

As Gilbertson’s interest in her old passion revived, she and Elizabeth Balneaves – a painter, writer and filmmaker who had retired to Shetland – planned a film trip to the Canadian arctic. Balneaves, 10 years Gilbertson’s junior, fell ill and Gilbertson went on alone.

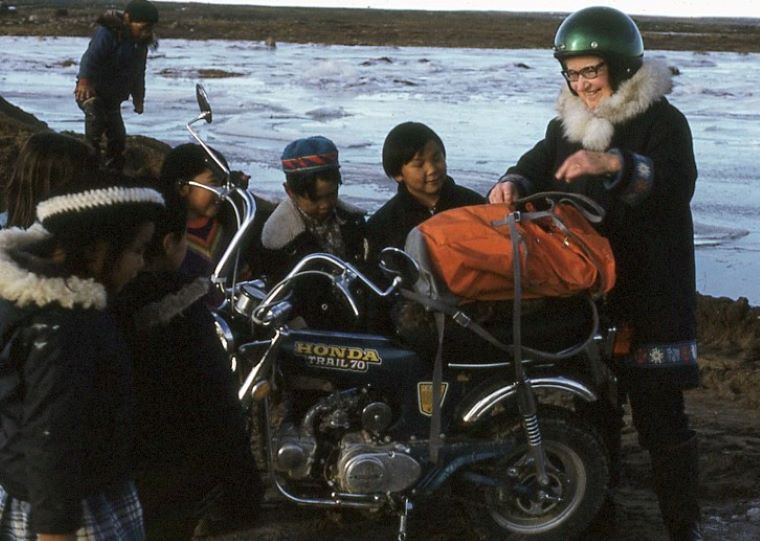

Gilbertson was nearly 70 when she arrived in the arctic, remaining until 1978.

“She came with a minimum of equipment,” says Main. “What she had to spend was time; time to get to know her subject, and time to develop her vision.”

As she had done in Shetland, Gilbertson set about filming the everyday lives of people, including their traditional practices.

“Some of the narrative has a colonial slant,” continues Main, “but Jenny was not interested in presenting films of romance or victimization. Her goal was simply to show the ordinary lives of folks, to let the rest of the world know how life was lived in the arctic.”

When Main herself arrived in those Inuit communities, she sought out people who had met Gilbertson or who had worked with her.

“I was able to film some of them and I got a lovely recording from one individual.”

She quickly learned that the north – Grise Fiord is believed to be one of the coldest inhabited places in the world – is hard on equipment, sometimes causing cameras and sound recorders to simply shut off.

“I kept my camera in a Ziploc bag when I wasn’t using it. Otherwise, I was dealing with constant misting as I went from warm to cold.”

Main may have had more physical comforts and greater access to technology than Gilbertson, but she grappled with how she would make her own film.

“I wanted to respect Jenny’s methods and I wanted to make an ethical film. I would form an idea for a shoot and then find that people would want to do something quite different, so it was a real challenge.”

As an academic, she tried to balance her passion for Gilbertson’s fiercely independent spirit with a critical eye and analysis.

“To be perfectly honest, there are a couple of her films I don’t like but I am still intrigued by this woman who wrote, directed, staged, filmed and edited her own work. To me, she is legendary.”

The lengths that Gilbertson would go to tell the stories she considered important was remarkable.

That passion is perhaps best evidenced in her 25-minute film Jenny’s Dog Team Journey, which can be found online. As witness to the growing reliance upon snowmobiles in northern communities, she flew to Igloolik and connected with a dog sled owner. With a team of 21 dogs, he took Jenny, his nephew, his nephew’s wife and their three-month-old daughter on a two-week journey 500 kms south to Resolute Bay.

Each night of the journey over sea ice and barren hills was spent in a newly constructed igloo, dining mostly on hard biscuits, frozen cheese, canned sardines and tea.

At the end of the film, a spirited Gilbertson – then 75 – expressed her satisfaction with capturing a nearly extinct custom. She then spent another year filming daily life in Grise Fiord before going to Ottawa to edit her films and later returning to Shetland.

Tulloch is thrilled that Main has taken such an interest in her grandmother’s work.

“For my sister and me she was just Grandma – a Grandma who wasn’t around much for many years, but we are gradually learning more of her story and it is a remarkable one.”

Story by Rosalie MacEachern

My family and I loved Jenny. We met her in Coral Harbour. We even got her to baby sit once.

Jack Cooper

Great story. My great, great grandparents were Gilbertsons from Glasgow. They became shopkeepers in Philadelphia, Pa. after migrating to the US. The picture of Jenny looks so much like my great Aunt Marie. I need to do some genealogy! I hate the cold and live in Florida!