40 years ago, with banjo and guitar in hand, Californian Kevin Carr wandered the land of his Irish ancestors for four months in search of roots, connection and culture.

“In an uncharacteristically bold move for a mostly shy young man, I went to Moran’s Pub where the Tradition Folk Club was held in Dublin and asked to be a floor singer,” he recalls via email. “The man running it, Kevin Conneff, later of Chieftains fame, could not have been more welcoming to an unknown musician off the street, and let me sing a couple of songs with my banjo.”

The main act that night was a group of Sligo-based American players known as Pumpkinhead. Carr remembers their music as “revelatory,” adding that they rivaled the renowned Irish band Planxty in popularity.

Carr recognized their guest fiddler Marty Somberg from his days busking on the streets of Santa Cruz, California. Somberg introduced him to the various band members, including Thom Moore.

“Thom generously invited me to visit if I ever got close to Sligo. At the time, however, I couldn’t see myself ever taking him up on his offer.”

As fate would have it, he was in Sligo only a month later and, when his Volkswagen van broke down, he stuck out a thumb and hitched a ride with someone who knew Moore. To his surprise, rather than finding a mechanic, Carr was installed in a guest room and rushed off to meet the renowned Irish fiddler Joe O’Dowd.

“The next night was a session, and the next was a visit with Rick Epping and Sandi Miller for more music. And finally, when I found a mechanic, of course it started without a hitch and never gave me a moment’s trouble for the remaining months of my visit.”

Carr was driving Somberg to Shannon airport when they stopped at a farewell gathering for accordionist Joe Cooley, who had spent his working years in the United States and had returned home to die.

“Many of the great players within four counties were there to honour Joe, including television producer Tony MacMahon, who filmed the long night of music.”

For the young American, the wondrous experiences that arose from simple car troubles were almost mind-boggling.

“I felt like I had been dropped in the deep end of a pool of music and culture and wanted to stay in the rest of my life.”

On returning to the States, Carr learned that his grandfather Dennis McGough had been a fiddler and a square-dance caller. It was enough to send him in search of a fiddle of his own. He then connected with fiddler Bill Jackson, who taught him his first Irish tunes.

“I continue to play today because traditional music connects me to culture and emotion in a profound way. It is challenging, energizing and deeply satisfying to spend time in the vast pool of music which has nourished, and been nourished, by so many grand souls through the centuries.”

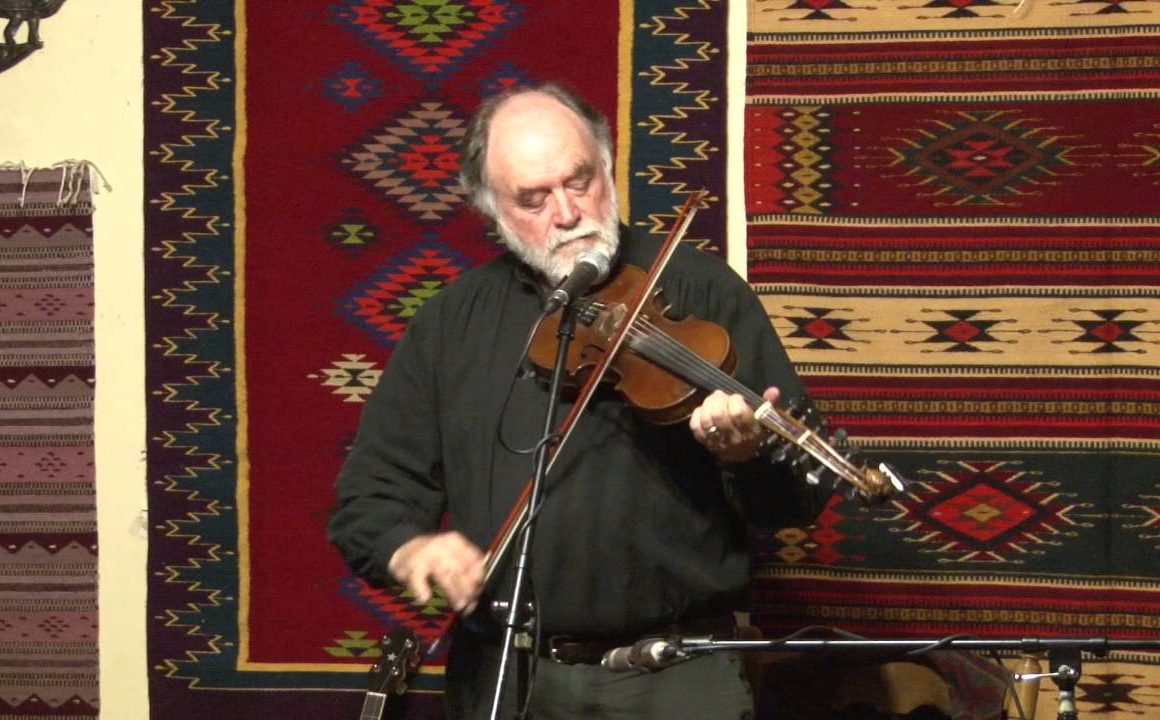

Carr, who favours an old American fiddle of unknown origin given to him by a friend, considers himself to be a traditional player who incorporates elements from other players that he admires.

“I describe my style and sound as being rooted in Irish music, with a strong Quebecois influence on my bowing, and a hint of my grandfather’s Pennsylvania touch. I never actually heard him play, so that element must be epigenetic.”

A good tune, he notes, is marked by a memorable melody, a strong rhythmic sensibility, and emotional depth.

Carr’s musical highlights over the years include being associated with the Festival of American Fiddle Tunes, playing in a traditional band from Galicia at the Kilkenny Irish Festival, joining Wake the Dead at the famous Fillmore West, and teaching at Alasdair Fraser’s Sierra Fiddle Camp. His future plans include recording some favourites with family, playing Basque music, fiddling for dances and performing with Hillbillies from Mars. He also plays in a duo called Orujo, which explores links between medieval and modern Galician music.

“Crazy, isn’t it?” he smiles. “To think that all that musical magic started in Sligo all those years ago when the damn van wouldn’t start!”

Leave a Comment