On day four out of Oban, sailing with Adventure Canada, my wife and I awoke to find ourselves anchored at Isleornsay Harbour off the Isle of Skye. This was not a planned stop. Overnight, faced with southwesterly winds gusting to 60 and 65 knots, the captain had taken the Ocean Endeavour north into the Sound of Sleat that runs between Skye and the mainland. Here he had found shelter in one of the most protected harbours on the east coast of Skye. To me, this proved revelatory.

I had been working on a book about Scottish Highlanders who emigrated to Canada in the 18th and 19th centuries. Some made the move of their own volition, but many were refugee victims of forced evictions called the Highland Clearances. During one of the most ferocious, a ship called the Sillery anchored at Isleornsay early in August of 1853. It had arrived to carry mainland crofters evicted from Knoydart in Glengarry. They lived and farmed along the north shore of Loch Hourn, a broad inlet that lies across the sound due east of Isleornsay.

I had wondered why the Sillery had not proceeded into that inlet to reduce transport time. Hence the revelation – one of those serendipities that can arise with surprising frequency on these voyages. Onboard experts explained that strong westerly winds – not unusual in these parts – would have made it difficult for any 19th-century sailing vessel to emerge out of that inlet. So the Sillery, like our own vessel, had anchored in this sheltered harbour.

Just over a century before, farmers from Knoydart had been among the 600 Highlanders who had followed the chief of Glengarry into the 1746 Battle of Culloden. In the decades following that catastrophe, some had emigrated to Upper Canada, where after the American Revolutionary War, Scottish Loyalists had established a foothold.

Just over a century before, farmers from Knoydart had been among the 600 Highlanders who had followed the chief of Glengarry into the 1746 Battle of Culloden. In the decades following that catastrophe, some had emigrated to Upper Canada, where after the American Revolutionary War, Scottish Loyalists had established a foothold.

Knoydart had been bleeding people to those environs ever since.

But in 1847, more than 600 people remained in the coastal settlements. The Great Famine reduced their numbers by a third, but those still resident, according to activist-lawyer Donald Ross, could have thrived as farmers with a little encouragement. In 1852, however, the newly widowed Josephine Macdonell gained control of the Knoydart estate. A Lowland industrialist named James Baird – a Tory Member of Parliament – had expressed interest in her lands, but only if they were unencumbered by paupers for whom he would legally become responsible.

Ignoring the people’s offers to pay arrears caused by the recent famine, the widow Macdonell issued warnings of removal. “Those who imagine they will be allowed to remain after this,” she wrote, “are indulging in a vain hope as the most strident measures will be taken to effect their removal.”

In April 1853, she informed her tenants that they would be going to Australia, sailing courtesy of the landlord-sponsored Highland and Island Emigration Society. In June, she amended that: they would travel instead to Canada, their passage paid as far as Montreal. On debarkation, they would each be given ten pounds of oatmeal. Beyond that, they were on their own.

On August 2, 1853, with the Sillery anchored at Isleornsay, men with axes, crowbars, and hammers rowed across the inlet and began clearing farmers from their homes. The factor in charge, one Alexander Grant, ordered that after removing the tenants, his men were immediately to destroy “not only the houses of those who had left,” Donald Ross wrote, “but also of those who had refused to go.”

Gangs of men ripped off thatched roofs, slammed picks into walls and foundations, and chopped down any supporting trees. Eventually, Ross noted, “roof, rafters, and walls fell with a crash. Clouds of dust rose to the skies, while men, women and children stood at a distance, completely dismayed.”

“The wail of the poor women and children as they were torn away from their homes would have melted a heart of stone.”

The factor and his men proceeded methodically through one settlement after another, destroying everything but a few huts that belonged to declared paupers who remained protected by law. He warned these impoverished people that if they gave anyone else shelter, “for one moment by day or night,” he would level their homes as well.

The marauders hauled everyone else out of their houses, threw their furniture and possessions after them, then set about the work of destruction. Ross writes that a few able-bodied men could have seized the factor and his men, bound them hand and foot, and sent them out of the district. But they “stood aside as dumb spectators,” he wrote, because they knew any such resistance would end with themselves in jail and their wives and children left to fend for themselves. And so “no hand was lifted, no stone cast, no angry word was spoken.”

The initial destruction went on for a week. On August 9, the Sillery departed for Montreal carrying 332 newly created refugees. In Knoydart, when the gangs departed, about sixty people emerged from the rocks and the ridges, most of them old and decrepit, but among them a few children. They set about creating what shelter they could. They were still working in the wreckage when, on August 22, the marauders returned and launched a new wave of demolition. Over the next weeks, the destroyers returned again and again.

The initial destruction went on for a week. On August 9, the Sillery departed for Montreal carrying 332 newly created refugees. In Knoydart, when the gangs departed, about sixty people emerged from the rocks and the ridges, most of them old and decrepit, but among them a few children. They set about creating what shelter they could. They were still working in the wreckage when, on August 22, the marauders returned and launched a new wave of demolition. Over the next weeks, the destroyers returned again and again.

In November 1853, when Donald Ross arrived from Glasgow carrying tents and supplies, he found sixteen families subsisting among the ruins. He told their stories in a 31-page pamphlet, a howl of protest entitled Glengarry Evictions or Scenes at Knoydart in Inverness-shire. Ross was a vivid writer and in 2018, as I gazed out across the water from the Ocean Endeavour, I could not help recalling some of the scenes he recreated.

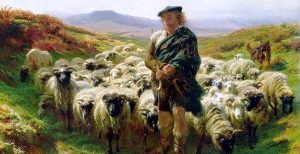

Within six months, the widow Macdonnell’s factor had removed almost all of those who – “for motives of charity” – had been allowed to remain through the winter. This time, they were removed with a medical officer in attendance. Soon enough, protected by a provision in his lease prohibiting him from sheltering any of those evicted, industrialist James Baird planted sheep in the surrounding hills. In 1857, with all the people dispersed, Baird purchased the Knoydart estate. He built a grand house and used it from time to time as a country retreat. ~ Story by Ken McGoogan

Ken McGoogan’s books include How the Scots Invented Canada and Celtic Lightning: How the Scots and the Irish Created a Canadian Nation. Ken sails every year with adventurecanada.com

Hi I believe my Ancestors are from this area. If someone can share more information with me that’d be great. I really want to know more of where my ancestors came from. I have information i can share.

If your on Facebook. Join the lochaber group. And ask. Might point you closer.

Mccheachan was from that area.