There is a tentative “Hello?” followed by an embarrassed chuckle before Louise Kennedy’s image bursts onto my laptop screen. Apologizing for being late, she explains that she has been in bed, unsure if she is suffering the side effects of her first COVID-19 vaccination. Thankfully, she isn’t.

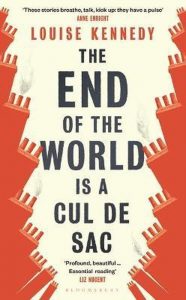

At 53, Kennedy is one of Ireland’s most successful emerging writers. Her debut collection of short stories, The End of the World is a Cul-de-sac (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021) went to a nine-way auction. In 2019 and 2020, her stories were shortlisted for the £30,000 Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award, and her debut novel will appear next year.

Such success is remarkable by any standards. It is especially so for Kennedy, who only began writing at 47 after working as a chef for nearly 30 years.

“It’s kinda’ weird,” she says, “having to think of myself as a writer now, instead of a chef with notions.”

Kennedy may be witty and self-deprecating, but her stories are dark. They portray a contemporary, troubled Ireland where relationships struggle in hostile circumstances: a marriage doomed by an abortion, ‘ghost’ housing estates built and abandoned on the roar of the Celtic Tiger, a farmer operating a cannabis factory to pay off debts, people haunted by the legacy of Northern Ireland’s 30-year conflict.

Life is challenging and often cruel for her female protagonists.

“They are the characters who came to me. Maybe it is because of the national discourse when I was writing – about the economy, the campaign to repeal Ireland’s ban on abortion, women taking responsibility for caring, things like that. And I see many lonely people in relationships that aren’t working.”

What sets Kennedy’s stories apart is the rich vein of Celtic culture and tradition that underlies them, fusing the modern with the ancient. References to fairy forts, healing wells and megalithic tombs, and the ancient Irish belief that “hares were shape-shifters related to the sídhe, because a hare screams like a woman when it is hurt.”

“I have always loved that kind of thing. One of the first books my mother bought me was Sinead de Valera’s Irish Fairy Tales. But I think, too, it is about where I live.”

Kennedy was born in Belfast but now lives in Sligo, a town on the Wild Atlantic Way. The home she shares with her accountant husband is “a 1960s, semi-detached house in a cul-de-sac,” she notes, “bought in a hysterical Celtic Tiger decision.”

“I live in an estate in town, and I look through the window at lots more houses like my own. But from one of the windows upstairs, I can see Queen Maeve’s Cairn, built around 3000 B.C. with a passage tomb beneath it. In Irish mythology, Maeve was a queen of Connacht.

“One of the biggest megalithic burial sites in Europe is just two kilometres away. There is a 1940s housing development here built around a little stone burial site. The workmen wouldn’t touch it and priests placed statues between the ancient stones. According to folklore, disrespecting these tombs brings a curse.”

One of her favourite places is Hazelwood, an ancient woodland immortalized by the Irish poet, W.B. Yeats in The Song of Wandering Aengus. It is where her two children, now 21 and 18, took their first steps.

“This ancient culture, it’s right here. It’s all around me. It seeps into you. It is kinda’ strange, that sense of people being here before you and leaving their mark. It is hard to avoid it coming out in the writing.”

Kennedy’s family moved from Belfast to Holywood, County Down at the height of ‘the Troubles.’ As Catholics, she shares, they were hugely outnumbered there by Protestants and felt vulnerable and exposed.

“Catholics with businesses were easy to identify. Our names were over the door. A neighbour was killed by loyalists. As a 5-year-old, I shouldn’t have known that, but I overheard adults talking about it and spent a lot of my childhood distraught that my father would die the same way.”

When the family’s pub was bombed for a second time, they moved to the Republic. Kennedy graduated in Social Science from University College Dublin and worked briefly as a social worker in both Dublin and London.

“But I couldn’t do it. I was a sponge for other people’s misery.”

She returned to Ireland after “a year in an horrific job in a London bank, putting microfiches into alphabetical order.” But London, and the availability of ‘exotic’ ingredients unheard of in Ireland, had awakened her interest in cookery. She borrowed the money for a Cordon Bleu course and began her 30-year career as a chef in Ireland and, in the nineties, Lebanon.

She returned to Ireland after “a year in an horrific job in a London bank, putting microfiches into alphabetical order.” But London, and the availability of ‘exotic’ ingredients unheard of in Ireland, had awakened her interest in cookery. She borrowed the money for a Cordon Bleu course and began her 30-year career as a chef in Ireland and, in the nineties, Lebanon.

‘Kinda’ weird,’ ‘kinda’ strange,’ and ‘kinda’ remarkable’ are phrases that pepper our ninety-minute Zoom conversation, as though life constantly takes her by surprise. Writing never featured in Louise’s plans but, in 2014, a friend coaxed her to accompany her to a writing group.

“I had never written anything, and I didn’t want to go. All the others were already writing, and I made a fool of myself, telling them I was only there because my friend made me go. I felt intimidated and out of place. It was upsetting but kinda’ weird too. I must have been curious because I went back again.”

Later that year, Ireland’s economic downturn forced Louise to close the bistro she had opened in 2007. But she discovered, at 47, she was finally doing what she was destined to do.

“I have found myself flooded by words and ideas ever since. The process of writing felt familiar. I was used to turning up to work when I didn’t feel like it. I was used to putting in long hours, trying to apply discipline to create something, trusting that going through the motions would eventually yield something. I think my circumstances focused my writing. It was a mental escape from debt and stress.”

Kennedy is slowly adjusting to her success, having initially found it quite overwhelming.

“It was exciting, but it was a lot to take in. Publishers were love-bombing me and I was having to take their calls in the kitchen of the library where I should have been working. I cried a lot. Before that, it was just me getting up in the middle of the night and putting on my dressing-gown to go out to my shed to write. I started to realize things were getting serious.”

Much of the publicity surrounding the scribe’s success has focused on her age. That doesn’t bother her, she says, although she rails against the emphasis put on ‘young’ writers.

“I have had lots of women telling me they are feeling encouraged that I started writing very late. They are starting to believe that they can give it a lash in their 40s, 50s and 60s. Most women these days are working, in jobs as demanding as men’s. They give birth to the children. They often end up caring for parents. It is really hard. I don’t know how they’re supposed to tap into any kind of creativity with so much on their plates.”

Like many things in her life, her forthcoming novel follows an unexpected turn of events. In March 2019, while procrastinating about finishing a PhD on the Irish writer, Norah Hoult, Kennedy was diagnosed with melanoma and underwent several rounds of surgery. Confronted with the prospect of death, she gave herself three months to complete a novel, writing five thousand words every week.

Her doggedness, the willingness to turn up when she didn’t feel like it, saw her complete “a shockingly bad first draft” that her agent later submitted with her story collection.

“When I Move to the Sky is set in the North of Ireland. It is about a teacher in her 20s whose family’s pub is blown up. Sounds familiar?”, she laughs. “The woman has a relationship with someone she shouldn’t go near. She is kinda’ good craic, but things are chaotic, out of control.”

She hopes that, at 53, she has done her last shift in a kitchen. In terms of writing, however, she admits there is no way to circumvent the hard work.

“It is not like I just sit down, write 4,000 words and win a prize. I could spend months on a story and lose sleep over it. The amount I have written since I have started is nuts, but I still have to turn up every day and flex the writing muscle.’

Twenty-one years ago, when she was in the final throes of labour with her son, a midwife leaned down beside her. ‘You’re not that Louise Kennedy, are you?’ she asked, referring to the internationally renowned Irish fashion designer of the same name.

As a wonderful new Irish voice, there is little doubt that in the future this writer will be recognized as that Louise Kennedy. ~ Story by Eimear O’Callaghan

Leave a Comment