Whether our stories speak of snow-swept landscapes, backdrops of berry- studded holly bushes, or darkened, shuttered streets, we cherish them because they are our own burnished composite of past and present.

The Barra MacNeils, who take their name from their clan’s ancestral home on Scotland’s west coast, sing their way across Canada from mid-November to mid-December each year. Lucy MacNeil and her brothers combine their caroling and instrumentals with fond memories of Christmas on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia.

“Santa always came to our home in Syndey Mines,” she recalls “But later in the day we were all bundled into the station wagon and off we went to our grandmother’s house in Washabuck, which was an hour’s noisy drive away. The snow always seemed to be falling on that drive.”

More often than not, the car could not make it up the snow-covered country driveway.

“A toboggan would be brought down, and it would take a couple of trips to carry the children, presents, food and overnight bags, including cloth diapers in those days.”

As the family climbed the hill to the farmhouse, they would hear music in the distance. Opening the porch door, MacNeil and her siblings were hit with all the sights, sounds, and smells of Christmas.

“I can remember as a little girl, reaching up and lifting the latch to the kitchen door, to a room filled with joy and music and singing and dancing. My grandmother, Mary Ann MacKenzie, would be sitting by the wood fire, welcoming everyone. There would be aunts and uncles and cousins and the music and dancing would go on and on.”

Family members took their turn at the piano or on the fiddle or singing a Gaelic song while excited children raced around.

“If we got too rambunctious, or in the way of the dancers, we were all sent out to play on the hill – which was no punishment at all.”

As is tradition, the Barras’ Christmas tour begins on Canada’s west coast, each show bringing them closer to Cape Breton.

“Every year people tell us that we have brought them some Christmas spirit, and we truly take joy in that. As the tour goes on we become almost like children at Christmas ourselves, only now the excitement is to get home so we can spend Christmas with our own families.”

These days the Barras gather at their parents’ on Christmas Day, but make the trip to Washabuck on Old Christmas to celebrate with their uncle, renowned fiddler Hector MacKenzie, whose compositions are part of their repertoire.

In the Northern Ireland of Ken McElroy’s youth, the Christmas rhymers – costumed and faces blackened with soot – turned up at farmhouse doors in the days leading up to Christmas. Their revels included a captivating battle with wooden swords.

“They would make their boisterous appearance at a farmhouse door with a loud knock. Each character was dressed in traditional costume. St. George may have had a crown and a red cross on his tunic. St. Patrick sometimes wore a mitre with a green robe. Oliver Cromwell always had a long nose made from a paper crown.”

As they filed into farmhouses, each character would begin their skit with the rhyme: “Room, room, gallant boys, Pray give us room to rhyme, We come here in jest and fun, Upon this Christmas time.”

The rhymers, each of whom added a verse to the skit, provided welcome entertainment on the long December nights. McElroy points out, however, that they also collected small amounts of money to provide Christmas groceries, or a bottle of sherry or bag of coal, for the poor and elderly in the area.

The rhymers, each of whom added a verse to the skit, provided welcome entertainment on the long December nights. McElroy points out, however, that they also collected small amounts of money to provide Christmas groceries, or a bottle of sherry or bag of coal, for the poor and elderly in the area.

“Sadly, the Christmas rhymers have long since disappeared, and only people now in their sixties, seventies or eighties would have had the pleasure of seeing their rustic dramas. Thankfully, one or two groups of enthusiastic actors – particularly in County Armagh and County Fermanagh – keep the tradition alive, although they no longer travel around the country roads and farmhouses of Ulster.”

Journalist Eimear O’Callaghan – who recently published her first full-length book Belfast Days: A 1972 Teenage Diary – recalls two particularly grim Christmases growing up in West Belfast during The Troubles.

“This Christmas Day was celebrated by the internees with a hunger strike, by people in Andersontown keeping a 24-hour fast outside the church, by 4,000 people who gave up their homes on Christmas Day to defy the British army and walk 10 miles to Long Kesh internment camp, and by the 14,000 British soldiers separated from their families to keep our riot-torn city at peace,” the then 16 year-old wrote on Christmas Day, 1971.

O’Callaghan points out that, despite the difficulties, her parents – and thousands like them – did their best to adhere to Irish Christmas traditions.

“We had gifts from Santa Claus, lovingly arrayed beneath a twinkling tree…a roast turkey dinner with all the trimmings…and Midnight Mass, followed by sandwiches of freshly roasted ham. At church we prayed for those who had lost their lives in the shootings and bombings of the year gone by.”

The following Christmas, she voiced her dread of the coming New Year – 1973 – writing that she hoped she, and all her family, would still be alive to see the following holiday season.

“For 30 years the Christmas message of ‘goodwill to all men’ flew in the face of what was happening on our streets. We lived with the threat of violence all year round, but it was during the season of “peace on earth” that the horror of what we were enduring was most keenly felt.”

Christmas became a time for taking stock – “for reflecting on the ever-mounting tally of deaths and continued political failure,” she notes, adding that for many families the season was a painful reminder of who was missing from the dinner table, either through death, injury or imprisonment.

“Thankfully, Northern Ireland is now at peace, but the painful legacy of the conflict endures. In the midst of celebrations and seasonal cheer, relatives and friends of the thousands killed will feel their loss more keenly than at any other time of year. The lucky ones among us reflect on, and give thanks for, our good fortune at being spared.”

Californians Gerry Herter and his wife, Loretta, flew to Ireland a dozen years ago for an Irish Tenors’ holiday tour. On Christmas Eve, in Kenmare, they walked to the nearby Protestant Church. A few minutes into the 11 p.m. service, they were startled to see a man in clerical garb walk down the centre aisle and up into the pulpit.

“He turned to the congregation and said, ‘I’m Father Murphy from Holy Cross Catholic church. This is the first time I have been in this pulpit. I bring you greetings from your brothers and sisters at Holy Cross. And if you’ll allow me, I would like to offer a blessing and prayer for you.’”

Herter recalls the priest delivering a touching message of peace, hope and love, before embracing the minister and walking out of the church.

“When he continued the service, the minister said, “After we are done I am going to walk over to Holy Cross (for midnight mass) and bring our greetings to them.”

Herter was humbled to witness the Christmas Eve exchange between priest and minister, seeing in it the hard work of all those who contributed to and embraced the peace process.

American travel professional Stephanie Abrams has found the Irish hospitality blends perfectly with her idea of Christmas, and has spent the past eight Christmases in Eire.

“Home Alone Syndrome afflicts only children like myself when the holidays appear,” she shares, adding that she had a very hard time finding a place to stay for her first Irish Christmas.

“I tried to reserve a space online for Dec. 24 to 27, but there was never a room at the inn because they were all closed.”

Patsy O’ Kane, owner of Beech Hill Country House in Derry, happily solved Abrams’ problem.

“She explained to me nothing is open at Christmas. I thought we might end up sleeping in our car rental, but Patsy said, ‘No, no. You’ll come here and have the place to yourselves. We’ll give you the keys.’”

Carl Gough, a storyteller who lives in a rural area outside Swansea, Wales, has researched the Christmas traditions of his adopted home.

Carl Gough, a storyteller who lives in a rural area outside Swansea, Wales, has researched the Christmas traditions of his adopted home.

“The Mari Lwyd is currently experiencing somewhat of a comeback in Wales. Similar to the hobby horse, a decorated skull of a horse is paraded through the streets accompanied by bawdy revelers out to create mischief, sing songs, recount rhymes and welcome fortune during the dying of the year. Her appearance, in truth, occurs from the Wassail, through to New Year’s but, in my experience, she has begun to be used in many fundraising efforts around Christmas time, especially travelling from pub to pub.”

He incorporates the Welsh tradition of Calennig into his own Christmas stories.

“Calennig is associated with the making of a Calennig apple, an apple with three sticks stuck in the base like a tripod with some sprigs of evergreen sprouting out of the top.

Some are decorated with ribbons and others with cloves, but all Calennig apples must have the three sticks and the evergreen. They were given out for good luck, shared with friends and neighbours and placed in windows to ensure the turning year brought good things into the household.”

Nova Scotia artist Richard Rudnicki, author and illustrator of A Christmas Dollhouse, found the Christmas spirit in a newspaper article about an elderly man old who built doll houses for sick children. He then met the man in question – Don MacKenzie – who told him of growing up in a small town during the Depression era, and of his family bearing the added burden of illness.

“Just before Christmas, his little sister saw a beautiful dollhouse in the window of a local store. Tickets were being sold on it and the townspeople saw how much the house meant to this little girl who had so little. One after another, they put her name in the draw to ensure she won it for Christmas.”

Rudnicki recounts how MacKenzie shared his hopes that with each new dollhouse he built, he would again see the very same look that he had seen on his little sister’s face that Christmas morning.

“There are things that touch us so profoundly as children, especially at Christmas, perhaps, that we carry them with us throughout our lives.”

Chloe Woolley, music director at Culture Vanin, grew up on a small stone-built croft above Ballaglass Glen on the Isle of Man. There, Christmas season, running from ‘Black Thomas Day’ – Dec. 21 – to Jan. 6, was once known as The Foolish Fortnight. Unlike most residents, her parents fetched water from a well, heated it on a stove for bathing, and lit the house with paraffin lamps into the 1980s.

“One Christmas morning, when I was little, my sister and I received the best Christmas present we could’ve imagined. Our parents led us out across the frosty field and into the dark stable and to our complete surprise, there was the softest, most beautiful young donkey. We always thought of her as our Christmas donkey.”

Hunt the Wren was also a regular part of her family’s Christmas tradition.

“In the Isle of Man we go round the streets in the morning of St. Stephen’s Day and anyone can join in the circular dance around the wren pole, accompanied by singing and dancing.”

She remembers staying at her grandparents in the capital city of Douglas on Christmas night, and the next morning joining the wren boys in the street.

“At noon the custom had to stop, as it is very bad luck after that. We’d go to the Woodburn Pub for a mince pie and drink, with whisky for the adults, before we returned to our grandparents for leftover Christmas dinner – fried mashed potato, carrot and parsnip. Delicious!”

“At noon the custom had to stop, as it is very bad luck after that. We’d go to the Woodburn Pub for a mince pie and drink, with whisky for the adults, before we returned to our grandparents for leftover Christmas dinner – fried mashed potato, carrot and parsnip. Delicious!”

Kearsley Waggoner was born on the Isle of Man but raised in the United States, where her mother maintained Christmas customs from her youth.

“In New Jersey we always had a Christmas pudding. Only my Manx mother enjoyed it, but we had it every year. Newcomers and guests were obliged to join her with the Christmas pud. We may not have been fans of her Christmas pudding, but her boozy trifle was always a big hit.”

Waggoner still has relatives on the Isle of Man and they are always in contact at Christmas.

“All the Christmas cards are usually mailed in one envelope to save on postage. The cousins send me Christmas cards printed with the sentiments in the Manx language because they thought it funny that I was learning Manx and they, who live there, have not.”

Alex Patience, a storyteller in Portskerra on the north coast of Scotland, remembers that Santa always paid a “promise visit” on Christmas Eve.

“Mid-evening there would be a loud rat-a-tat knock and I would run and open the front door and on the step there would be an old fisherman’s bag, tied around with rope, and no one to be seen.

Inside the bag would be a gift for every single person in the house.”

The excitement of Christmas Eve, however, did not carry over into the next day.

“Christmas Day in my house was nothing at all,” she recalls.

Her father, a herring fisherman, was often at sea at Christmas and she remembers her mother choosing the day for the annual washing of woolen blankets. She quickly escaped to the neighbours’ house, where they did celebrate on December 25.

“As a Scottish fisher family we never celebrated Christmas Day, but Santa did come to us ‘fisher bairns’ on Hogmanay. We’d wake up on January 1 to find our dad’s extra long fisherman’s stockings filled with small gifts, and a Satsuma in the toe. Other gifts were set out around the living room.”

In a carry-over from the Scottish Reformation, Christmas Day was not an official holiday in Scotland until 1960.

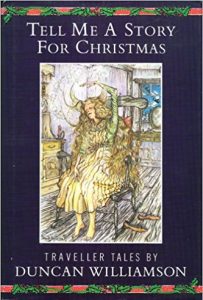

The very heart of Christmas tradition is captured in a tale told by the late Scottish seanchaidh, Duncan Williamson, later published in a collection titled Tell Me a Story for Christmas. In the account, Williamson recalled his own father sitting by the campfire on Christmas morning outside the tent they lived in along the north shore of Loch Tyne, with the family’s 17 children gathered round.

“Father would say, ‘Look children, its Christmas morning. Sorry I cannae give you nothing for your Christmas.’ And he took one orange, one single orange, and he took his pocket knife and he cut that orange in strips and he gave us each a wee bit out of it.

“Father would say, ‘Look children, its Christmas morning. Sorry I cannae give you nothing for your Christmas.’ And he took one orange, one single orange, and he took his pocket knife and he cut that orange in strips and he gave us each a wee bit out of it.

Christmas morning in the tent in the woods, with one orange, while all of the children in the nearby village were enjoying their Christmas presents.”

But Williamson’s father – a member of the Scottish traveler community, without a bit of tobacco for his pipe or a penny to his name – wasn’t done.

“I’m going to give you the greatest present of all for your Christmas; I am going to tell you a story.”

When he was finished the yarn, he added “You know, some day when I am gone and you are grown up and have your own family you will remember that story. I hope you do. But you wouldna’ remember a present if I could give it to you.

“Could anyone ever have given you a better gift in all your life?”

Leave a Comment