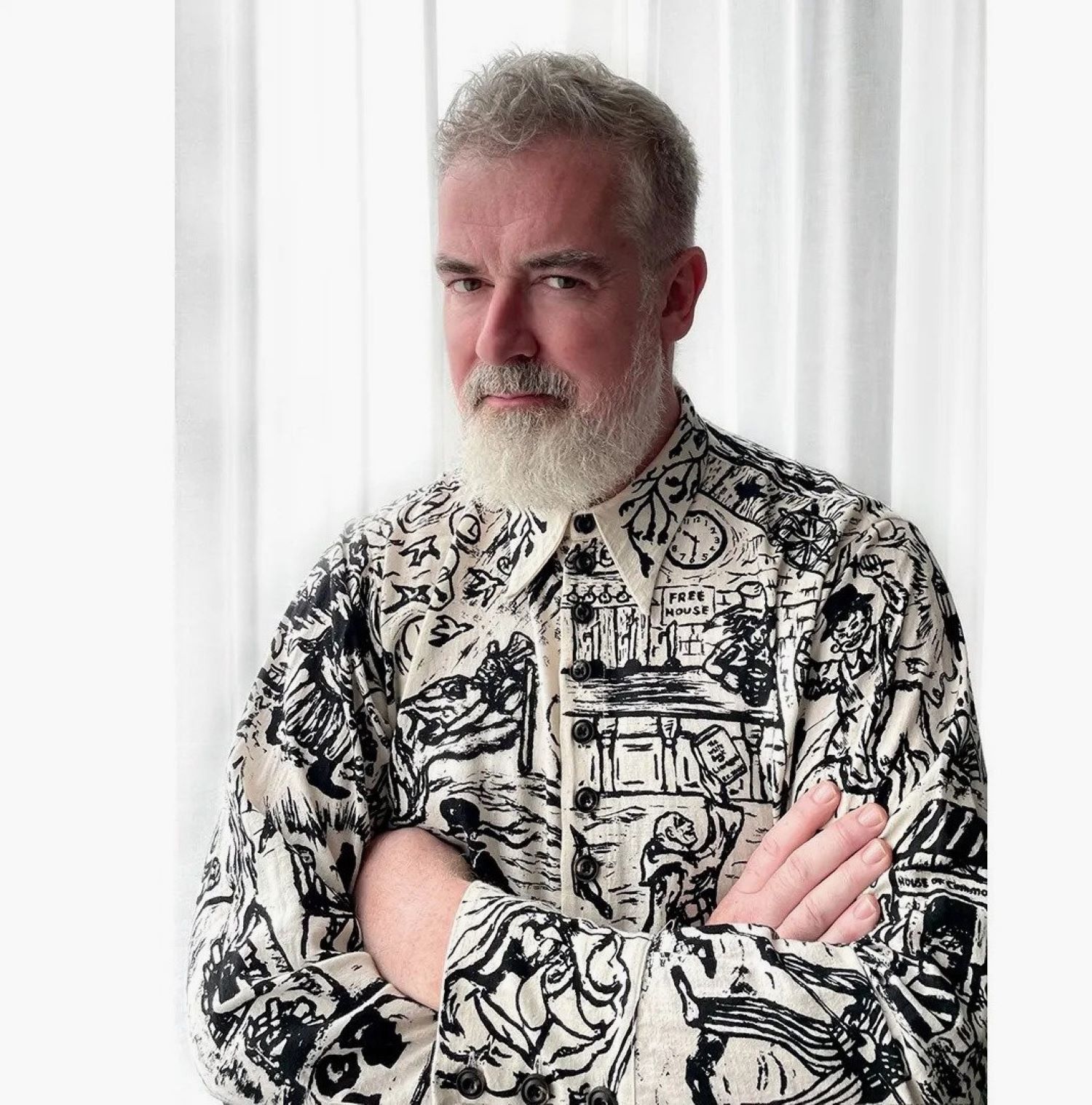

Mark C. O’Flaherty is a London-based photographer and writer who has worked with The New York Times, The Times, Sunday Times Style, Issey Miyake, Hermès, Knoll, Nobu, Diane von Furstenberg, Established & Sons, Richard James and Rupert Bevan, as well as international editions of AD, World of Interiors, Financial Times Weekend, HTSI, Elle Decoration, Marie Claire Maison, Ideat, Vogue Living, MiLK Decoration, and Interview. Recently we spoke with O’Flaherty about his latest book, Narrative Thread – Conversations on Fashion Collections.

What are your own roots?

My family is entirely Irish, although my parents left Dublin in the 1960s and moved to London, which is where I was born and largely grew up. But I spent most summers back in Dublin and I am proud to have an Irish passport.

When and why did you first become interested in fashion/style?

Growing up in the suburbs of London in the 1980s was the perfect place and time to become fixated on a new kind of design that was being generated by the capital, particularly by the club scene. It was 17 minutes on the train from my mum and dad’s house in Penge to Victoria Station. I was part of the pre-digital generation that grew up on i-D, Blitz and The Face. I spent any pocket money I could scrounge on clothes at Kensington Market and from the sales at Bazaar, where you’d see Gaultier and Galliano menswear for the first time. I studied film at what was then the School of Communication, next to the BBC on Riding House Street. Most of my teens and early 20s were misspent in Soho or getting the coach up to the Haçienda in Manchester to do the same up there.

Are they the same reasons that you continue to be involved today?

They are totally different today – because fashion is totally different. So is London. After college I moved into arts writing and music photography, and then fashion show production – working with Lee McQueen’s ex-partner, Andrew Groves, helping to launch his label. The world had its eyes on London as a fashion capital with a new sense of business savvy, but keeping so many plates spinning was beyond exhausting, so I moved into writing about fashion, and photographing the people I admired most. And I don’t think you can launch the kind of small-scale iconoclastic fashion label that we were trying to do, today. It’s like trying to run a restaurant – the profit margins are non-existent, unless you sell your soul and become McDonalds.

What are the challenges of the vocation?

What are the challenges of the vocation?

The fashion world is inherently shallow and attracts quite a lot of damaged people, so can be a wildly toxic environment. It’s like that brilliant scene in Showgirls – one of my absolute favourite films – where Nomi pushes Gina Gershon’s character down the stairs and breaks her hip, so she can get the lead role in Goddess. Bullying begets bullies, and I have always avoided any situation where I might become either. Or I hope I have. At the end of the day, it’s just clothes, and a lot of people lose sight of that. And you don’t have to go to every party to do the job and show everyone that you exist. But it’s still a serious business: 300 million people are employed by the industry worldwide, so we’re all trying to work out how we keep those people in jobs, while also getting our heads around the idea of circularity and not creating a lot of crap that people don’t need.

What are the rewards?

You are always seeing something new – even in a season when most of the big brands churn out something safe and commercial, someone somewhere is doing something radical. You learn things constantly. You get to meet inspiring individuals, and some genuine visionaries. You also get to see people develop, the longer you are around. It was amazing to see the trajectory of McQueen – I was the first person to interview him for print media, ever, and I just knew he was going to be huge. It is also amazing to see journeys of people like John Skelton and Giles Deacon, who are pointedly working outside of the usual models of the business – they are truly independent. And someone like Simone Rocha too, who works very much within the traditional model, but who has of course had so much support from her family. John Rocha is a good friend and one of the rocks of the fashion industry. I wish he was still designing menswear – he was as good as Yohji. But I’m also glad he has more time to go fishing now. You have to do what makes you happy, and I know Simone’s label makes him and Odette super happy.

What inspired the new book?

I had wanted to put together a book about Sandy Powell, the three-time-Oscar-winning costume designer. She started her career working with Derek Jarman, who I studied obsessively at film school. Despite a lot of support, we couldn’t make it work, because we couldn’t illustrate it properly, so I started thinking about the meaning of clothes that other people have kept as an archive. And what role they play in their lives. I spent a day with Carla Sozzani in Paris, shooting with her while she was curating an exhibition of her friend Azzedine Alaïa, who had just passed away. It was highly emotional for her, and I realized that every person’s connection to the clothes in their lives is emotional in a different way. It seemed like a great starting point for a project.

How did you go about choosing the interviewees?

I knew already I wanted Sandy Powell to be a chapter, because it was a way of reworking a lot of the plans we’d had for our book together. Carla has an incredible archive, and she was the inspiration for the bigger picture, so she was also an obvious choice. I wanted to cover all the bases in some way – young and old, various orientations, genders, and races. Carmen Haid was crucial because she represents eveningwear and that old school passion for Saint Laurent and the greats of the late 20th century, and vintage clothing as well. I was also thinking about this as an important historical document, because life comes at you fast, as the memes say. I had pursued Andre Leon Talley for quite some time, via our mutual friend Norma Kamali, and was crushed when he passed away.

Did the work go as originally planned, or did you end up with a book that was different from your initial vision?

I hadn’t originally planned Narrative Thread to really be something academic. But that is what it became, in part. It was originally going to be more of a coffee table book, with another publisher, but there were suggestions of photography that looked like candid snaps inside people’s wardrobes, and I didn’t want anything like that. I wanted to spend time with the clothes in a studio. But we projected an academic structure on it, so readers can dip in and out of the interviews and think about memory, identity, and product – which are the three things that I think define clothes.

What has the response been like so far – both popular & critical)?

There is always such a gap between finishing something and it actually appearing, so I had shelved expectations quite a lot. And then was blown away when review copies went out, and we had the endorsements we did. We had a great piece in HTSI, which is a magazine I’ve contributed to for over 20 years, but of course never been featured in. And Cathy Horyn spent hours interviewing me for her story for The Cut, which will probably remain a career high, probably forever. She is one of the few honest voices in fashion journalism, so her approval meant a lot to me. And so many people have been so generous with support, while we’ve had zero marketing budget. I didn’t think that I would ever be launching the book at the Rizzoli Bookstore in Manhattan, and that Gabriela Hearst would be hosting an after-party at Eleven Madison Park. I am forever grateful to everyone for believing in it.

What makes a good item of fashion/style?

The word “good” is really quite subjective. I think every item serves a different purpose. To me, it’s how it makes you feel. I have a mohair jumper from Filippa K that I live in, around the house, and it makes me feel so cozy. And whenever I wear any of John Skelton tailoring, I am always asked where it’s from – it attracts intrigue more than attention. It is nuanced and stylish, and looks age appropriate, which most menswear isn’t concerned with, as it is about selling to youth. Then there are remarkable objects in fashion history – like anything from Gaultier’s ‘Constructivist’ 1986 collection, inspired by Russian futurism, or the jumpsuits Miyake did in the 1980s, which offered a kind of luxury take on utilitarian uniforms.

What makes a good fashion/style photo?

The best fashion photographs are defined by their energy. I dislike the revival in skewed framing and bald/harsh off-camera flash. I felt like we did that to death already after grunge. Straighten the damn frame up! I like things that feel like a production, where everyone really cares about the clothes and wants to bring them to life. Before Tim Walker we had Guy Bourdin. What Irving Penn did with Issey Miyake was a marriage made in Heaven. Penn really understood the forms and how to shoot things like sculpture. Steven Meisel has always told a story through his shoots, and his roots are in something subversive and underground, and he can be so leftfield still. But then there’s always Bruce Weber, and Michael Roberts, who was so underrated. Who wouldn’t want to be photographed by him? He always makes everyone look so radiant and sexy.

What are your thoughts on the current state of fashion/style?

Most of the fashion industry is an amoral disaster currently, obsessed with selling anything at as high a price as possible to people who don’t care what it is, as long as other people know it is expensive. Which is why vintage is so much more interesting. The fashion that will have the most longevity isn’t online – it’s by designers who only sell to a few stores, and their prices are justified because of the time spent on the clothes, and how few pieces they make. I think there will be a major implosion in fast fashion and luxury fashion at some point, and a reset. I think a lot of people who previously would have been into buying the hot new thing are now actually making their own clothes. Because we want to feel a stronger connection with what we’re wearing and know how it was made.

What’s on your agenda for 2024?

I want to develop an interiors book. It will be quite dark, and based again around people’s personal collections – again, a very diverse range of people, each with a unique perspective on style. It will be about shadows, more than brightly lit bits of Ettore Sottsass and Eames. I would also like to collaborate on a few things with my husband, Neil DA Stewart, who is a genius fiction writer. His new novel Test Kitchen is out in the summer, and we are talking about maybe writing different books at the same, where some characters overlap, and share a space. I haven’t gone near fiction for a long time, but I think it could be a lot of fun. I am also looking forward to getting back to Japan for the first time in over four years and buying a vast amount of clothes at Chris Nemeth in Tokyo. The only denim I wear is from Nemeth – the cuts are so clever, and all based in the work he did while he was alive and thriving in London in the 1980s.

markcoflaherty.com

@markc_oflaherty

Leave a Comment