In the first of these articles, I described the start of my cycle journey across Europe, visiting sites associated with the Celts of the Iron Age and trying to understand their origins. It was becoming a journey of discovery in several ways. As I travelled between the sites, I was also reading historical and archaeological books and articles, trying to unravel a mystery – who were the people the ancient writers called Celts?

Where did they come from and what, if anything, links them to the people we call Celts today?’

Some of the sites I planned to visit were on my route; others would be more difficult to reach directly. Hannibal used elephants to cross the Alps and join his Celtic allies in their assault on Rome, and I thought I might need an elephant to carry all the weight on my bike over Alpine passes. Instead, I decided to follow the pan-European cycle route, Eurovelo 6, along the rivers Loire, Rhine, and Danube, staying north of the Alps. Two of the sites I would visit by public transport. The first of them, La Tène, was two hours from Basel by train. Switzerland has one of the best rail networks in the world.

In 1857, a local fisherman working for a rich collector discovered about 40 iron objects, including eight spearheads and 14 swords, at the mouth of Lake Neuchâtel near the village of La Tène. The full significance of the find only emerged gradually over the next few years, by which time private collectors had helped themselves to many of the objects which are now scattered around the world. In total, over 2,500 objects have been recovered from that part of the lake. In 1874, an international archaeological conference agreed to name the late Iron Age as the “La Tène period” – a name still in use today. When similarities were found between the style of objects found there and Iron Age finds in France, Britain, and Ireland, La Tène culture became associated with the Celts. Many archaeologists now question that link, but you will still find it all over the Internet, and in the Laténium museum on the shores of Lake Neuchâtel at Hauterive.

The museum’s press officer had warned me that the Celtic section was undergoing renovation. By the end of the year, it will house a much larger collection with interactive displays and the latest interpretations.

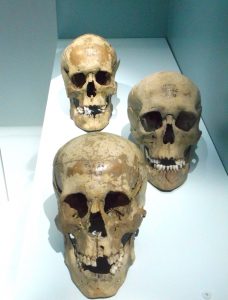

Despite those limitations it was well worth the visit. I passed through displays of earlier and later periods before reaching the Celtic section. There are well-preserved Roman sculptures and a huge flat-bottomed boat from the Gallo-Roman period. The Celtic section displays jewellery, weapons, a chariot wheel, and three human skulls. The objects found in the lake were put there over a long period of time. The reason for that may never be known for certain, but the preferred interpretation today is of a sacrificial site, where weapons, valued objects – and even people – were thrown into the water for ritual or religious reasons.

Before going outside to explore the surroundings I tried to operate one of the interactive displays. A girl who looked about five (I am not exaggerating) became concerned at my unsuccessful attempts. She asked me which section I was trying to enter, showed me the right way to do it and, when she was satisfied that I was following her instructions, went back to her own screen.

“So, you’re the expert?” I asked her.

“I come here often” she explained.

The museum is surrounded by an “archaeological park” with reconstructions of wooden dwellings from the different eras of occupation.

The most striking of these is a ‘palafitte’ raised on wooden piles, with a flat-bottomed boat like the one in the museum underneath. It stands on dry land, but the originals were built over the water. The Iron Age objects found at the La Tène site (about 5 km East of the museum) were thrown into the water from platforms or bridges built on similar piles; a reconstruction of the bridge where the three human skulls were found can also be seen in the park.

Entrance to the museum also gives you a free ferry trip along the lake to the town of Neuchâtel, 4.5 km away. The next ferry was in a couple of hours, so I decided to walk along the path that follows the shore. Along the way I passed the Hôtel Palafitte, with individual apartments jutting over the water on stilts.

The material and artistic culture called La Tène replaced the early Iron Age ‘Hallstatt culture’, which was named after the Hallstatt salt mines in Austria. They lay further along my journey. In the meantime, on the banks of the Danube in Southern Germany, lies the most important settlement of the ‘Hallstatt period’ – Heuneburg – where I was heading next.

From Basel, I followed Eurovelo 6 along the Rhine to Lake Constance, where I took a short-cut, climbing over some higher ground to re-join the route beside the Danube at Sigmaringen. On a river lined with hundreds of historic buildings, Sigmaringen Castle is one of the most impressive, but I was keen to press on – a couple of hours’ ride further East lay the ‘Celtic city’ of Heuneburg.

Like La Tène, the first archaeological discoveries at Heuneburg were made in the 19th century, but the full significance of the site has only become clear recently. At its height in the 6th century BC, Heuneburg was surrounded by an inner and an outer wall, enclosing the homes and workshops of 5,000 people within one square km. That might sound small by our standards but for its time and place it was unique. Today it is known as “the first city north of the Alps”. You may also find it described as “Pyrene, the Celtic City” mentioned by the Ancient Greeks, and that’s where things become more controversial.

In 1983, the village of Herbertingen opened a museum in a historic barn, a few kms from Heuneburg. As the importance of the site became clearer, in 1998 the European Union paid for a partial reconstruction of the original site. It is now an ‘open air museum’, managed by the state of Baden-Wurttemberg. There are longer-term plans to merge the two, but my visit began in the village museum, which contains many of the original finds.

All the displays are in German, although there is a booklet available in English. If you were thinking of visiting, and don’t understand German, it would help to read up beforehand, and there is quite a lot available online. As Brigitte Steinacher, the curator, showed me around, I was struck by one big difference between here and La Tène.

There were craftsmen’s tools, beauty accessories, fragments of textiles, and containers of Greek wine, but the only weapons were arrowheads and ornate daggers. They might have been used for hunting or ceremonial purposes instead of warfare, she said.

The heyday of Heuneburg pre-dated the La Tène artefacts by three centuries – it was a time of relative peace and progress. Then the site was destroyed by fire, for unknown reasons, and only partially rebuilt afterwards. By the 5th century BC, it was abandoned. The La Tène culture which followed, until the Roman conquest of the Celts, was more defensive and warlike.

An “archaeological” walking circuit 8 km long connects the indoor and outdoor museums with several surrounding sites. Of these, the most important is Hochmichele, the tallest burial tumulus in Europe. In a separate room at the museum, bathed in an eerie blue light, the burial chamber of a man and a woman in a chariot has been reconstructed. I decided to ride there on the way to Heuneburg.

I found it beside a forest track, with trees obscuring its summit, from where I could hear the laughter of children. When I arrived at the top, I found myself surrounded by about 20 of them from a local primary school. They asked me to take a photograph and agreed to take one of me. They were posing lots of questions when a whistle summoned them back down. At the base of the tumulus, I met their teachers and a guide from the Heuneberg Association. When I mentioned that it was my 60th birthday, they gave me some cake, sang Happy Birthday in German and Turkish, and roped me into a mystical ceremony. I was given two sticks and told to beat them in time as we marched round the base of the tumulus, trying to raise the spirits of the Celts buried there.

The guide took me to one side. The teacher was really motivating the children, she said, but the archaeologists would be unhappy if I wrote anything about mystical ceremonies. “We have to stick to the facts” she said. “Oh, I think the readers will understand the difference” I replied, thinking of Tolkein’s comment that “Celtic is a magic bag, into which anything may be put, and out of which almost anything may come.”

My first impression on reaching the Celtic settlement was: I can certainly see why they built it here. The reconstructed wall stands on the edge of a precipice, dominating the river and its vast plain, 200m below. Behind the wall stand several wooden houses and buildings used as workshops. A larger building stands further back on its own. This was a ‘manor house’ built after the big fire. As external threats were growing, it seems their society became more hierarchical.

Next to the houses, on a panel headed “Heuneburg – the Celtic City” is an image of Herodotus, the Ancient Greek ‘father of history’, who described the Danube “beginning in the land of the Celts and the city of Pyrene”. That quotation is the only written evidence linking Heuneburg with Pyrene, or the Celts. Unfortunately, he goes on to say that the source of the Danube lies beyond the straits of Gibraltar, which is clearly wrong and might suggest that the “Land of the Celts” was further West.

Next to the houses, on a panel headed “Heuneburg – the Celtic City” is an image of Herodotus, the Ancient Greek ‘father of history’, who described the Danube “beginning in the land of the Celts and the city of Pyrene”. That quotation is the only written evidence linking Heuneburg with Pyrene, or the Celts. Unfortunately, he goes on to say that the source of the Danube lies beyond the straits of Gibraltar, which is clearly wrong and might suggest that the “Land of the Celts” was further West.

Historians and archaeologists have been arguing over the meaning of those words for many years.

Today, the Celts are generally defined as the peoples who speak, or used to speak, Celtic languages. So, do we know what languages the people of Heuneburg or La Tène used to speak? The short answer is no. So, should we be using the same word to describe those people as we use today for the Scots, Irish, Welsh and Bretons?

I put this question to Dirk Krausse, the archaeologist who has led the excavations of Heuneburg for the State of Baden-Wurttenburg for 20 years. He pointed out that the term was first used by the Ancient Greeks, then he turned my question round, arguing that “it was misleading to name the linguistic group ‘Celtic’”. The main culprits were a Welshman called Edward Lhuyd and a Breton called Paul-Yves Pezron, who were both writing in the early 18th century. Krausse says that if they and their successors “had called the linguistic family say ‘Gaulish-British-Irish’, no one would speak of Celts in Scotland or Ireland nowadays. But it is like it is – quite complicated and misleading.”

Alas, had I been wasting my time seeking the origins of my ancestors and their culture, here in Central Europe? The picture was certainly more complicated than I first thought, but my search was not over yet. Since my first article about Gergovie, I have been riding backwards through time and that was set to continue with my journey towards Hallstatt. In the next of these articles, I plan to visit the salt mines and museum there and learn how recent history has influenced the Germany and Austria view of their Celtic heritage. ~ Story by Steve Melia / www.stevemelia.co.uk

Leave a Comment