Though Scotland is not a very large country, it is impressive how many Scottish place names there are scattered about Canada. One of the most curious is Calgary, Canada’s 4th largest city, which takes its moniker from a white sand beach and small hamlet on the Isle of Mull. A native Calgarian, I made the pilgrimage to the original Calgary about 15 years ago, and even had a dip in the chilly waters of Calgary Bay. When I asked a couple of other tourists on the beach if they could take a photo of me in the water, they asked me where I was from. “The other Calgary” I proudly declared!

Mull is the second largest island of the Inner Hebrides on Scotland’s rugged west coast. A thousand years ago it was in the domain of the Lords of the Isles, a semi-independent kingdom of maritime raiders. Prior to the Highland Clearances of the 1700 and 1800s, the island was home to more than 10,000 people. The clearances, the potato famine of the 1840s, and emigration, reduced it to less than 3,000 by the beginning of the 20th century – about the same as it is today.

The island is a popular tourist destination with throngs of visitors taking the ferry from nearby Oban to see its many castles, beaches, the holy island of Iona, and its picturesque capital, Tobermory. Tobermory was founded in 1788 as a fishing town, during the Clearances, as part of a program to provide both work and a place to live to displaced crofters. There is, not surprisingly, a Tobermory in Canada too. The name was given to a harbour at the tip of the Bruce Peninsula in Ontario.

The original Tobermory was built around a deep natural harbour with a curious history, just off the north coast of Mull. A gold-laden Spanish galleon (possibly the Florencia), part of the failed Spanish Armada, was anchored in the port seeking provisions in 1588 when its powder magazine exploded, sending her to the muddy depths. What caused the explosion is still disputed, but there is some evidence to suggest it may have been the result of a raid to steal the gold or a dispute about compensation.

The original Tobermory was built around a deep natural harbour with a curious history, just off the north coast of Mull. A gold-laden Spanish galleon (possibly the Florencia), part of the failed Spanish Armada, was anchored in the port seeking provisions in 1588 when its powder magazine exploded, sending her to the muddy depths. What caused the explosion is still disputed, but there is some evidence to suggest it may have been the result of a raid to steal the gold or a dispute about compensation.

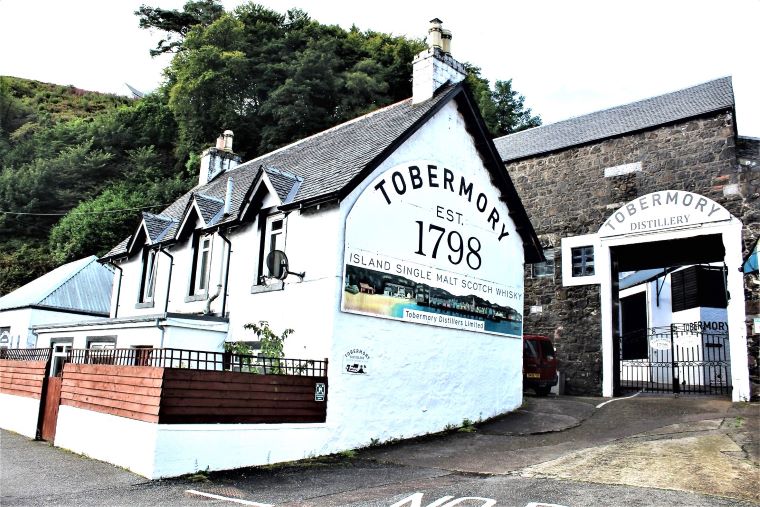

The Tobermory Distillery was built in 1798, 10 years after the town was founded and, as with many of the homes, clings to the edge of the bay.

Originally named Ledaig, pronounced [led*chig], the distillery would only operate for 40 years before closing in 1837. It was open again between 1890 and 1930, after which it sat silent for another 42 years. Like many others, the distillery was at the mercy of cyclical global demand for whisky production. It was refurbished and reopened again in 1972, only to close 3 years later when its owners went bankrupt.

Under fresh ownership it opened again in 1979 under a new name: Tobermory Distillers Ltd., but temporarily paused production between 1982 and 1989, the worst years of the most recent market correction. In 1993, the distillery’s fortunes turned, seemingly forever, when it was acquired by Burn Stewart Distillers, the owners of the Black Bottle Blended Scotch whisky. Today the distillery produces both peated (Ledaig) and unpeated (Tobermory) single malts, which are widely available. The peated version, Ledaig, is very rubbery and medicinal in style, and likely the only whisky more divisive amongst single malt enthusiasts than Laphroaig.

The distillery’s production is small – less than 1,000,000 liters a year – and unlikely to grow much, owing to its cramped conditions sandwiched between steep cliffs and the bay. The distillery’s stills are short but have both boil balls and very unusual lyne arms with an upward s-shaped kink. The result is a lighter spirit, though you would never suspect that after tasting Ledaig. Only a tiny fraction of the whisky is matured on site, with most of the distillery’s production matured on the mainland.

A short ferry ride from Oban, the Isle of Mull has plenty to offer visitors, not least a tour of Tobermory Distillery. The colourful buildings which ring the bay form a beautiful backdrop and make it one of Scotland’s most picturesque towns. Historic castles, black and white sand beaches, rolling hills and craggy mountains all add to its charm. Just off the coast there are two more reasons to visit. First there is the tiny holy island of Iona in the southwest, where – around its reconstructed Abbey – there are more monarchs buried than anywhere else in Europe. Second, the even smaller island of Staffa, home to Fingal’s Cave, a geologic formation connected to the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland. The haunting sound of waves crashing into the cave even inspired Felix Mendelssohn to compose an overture.

www.tobermorydistillery.com

www.kensingtonwinemarket.com

Leave a Comment