It has been said that spiritual awakenings are often preceded by rude awakenings.

That was certainly the case for Dubliner John Brierley. Seemingly set for life, Brierley had built a prosperous chartered surveyors’ business by the age of 39, enjoying the well-earned fruits of his labours.

“I was the perfect self-made man,” he tells Celtic Life International via Zoom, before solemnly adding, “and suddenly, my life was totally empty and meant nothing to me.”

On the verge of burnout, Brierley took a year off for a “business sabbatical” – spending time in nature and refreshing his mind and body.

“So many people spend their whole lives maybe doing something that they were never meant to do. As it turned out, I was becoming one of those people.”

The time off proved to be well spent.

“That was probably the most productive year of my life. It was then that I found myself on the Camino de Santiago.”

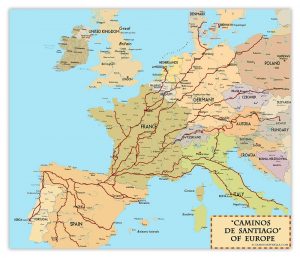

The Camino de Santiago – literally “Santiago’s road” in Spanish – is a series of pilgrimage routes leading to Galicia, the Celtic corner of Spain, and one of the seven Celtic nations.

In fact, Brierley’s sojourn was such a life-changing experience that he gave up his old career to dedicate himself fully to sharing the good word.

Interestingly, sharing the good word is practically the origin story of the Camino; it all started when one of Jesus’ disciples, James the Great, endeavoured to spread the gospel to the westernmost part of the known world.

“There may not be a lot of historical fact, but there is a lot of legend,” explains Brierley, who has since written 12 guidebooks for the various Camino routes. He also speaks around the world on the topic. “James had already agreed to go to the Iberian Peninsula.”

The disciple’s destination was a region called Finisterre, which is as far west as one can go in Europe. Back then, the western end of Europe was considered the end of the known world.

“That became the most important spiritual place on Earth, because when you reached Finisterre, when the sun sank in the west, it sank to Tir Na Nog, or the land of eternal youth. You could not get closer to the world of spirits, to God, to whatever the pagan worshipers of the time knew it as.”

Sadly, James wasn’t successful in his mission to convert the Iberian masses and was quickly beheaded upon his return to Jerusalem.

“His body, then, was brought back to the place where had sought to bring the message,” says Brierley, adding that even in death, James did not have much luck in Finisterre. “As a Christian, he wasn’t allowed to be buried there – he had to be laid to rest three days away. He ended up in a place called Librodor, which was a Roman town well-known for its burial site, which is Compostela.”

This site eventually came to be known as Santiago de Compostela, the capital of Galicia, and the end point of every Camino route. The path became a popular pilgrimage for Christians to take some few hundred years later thanks to the Spanish Inquisition.

“In the 11th century, the Crusades against the Muslims in the Holy Land meant that you couldn’t go there anymore,” shares Brierley. “What happened, then, was this massive swing to, ‘well, you can go to one of his apostles, who is buried in Santiago. That is pretty easy to get to’ – and that created a huge reorientation of the pilgrim traffic.”

Fast forward to about 25 years ago, when Brierley made his first pilgrimage. While, by his own admission, he isn’t particularly religious, he did encounter his fair share of Christians – and believers from all faiths – upon his journey.

“Indeed, when I walked up from Sevilla in the south of Spain one year, I only met one other pilgrim – a wonderful Japanese Shinto follower,” Brierley recalls, adding that, as the presence of organized religion became less prominent in people’s daily lives in the modern era, the Camino began attracting people from all walks of life – even atheists – to have a genuine spiritual experience.

“The Camino is very eclectic. It is every religion and none on this route, which is part of its power. And when we take the extra time out – particularly, for walking an overtly spiritual pilgrimage route – something magical happens.”

Annemiek Nefkens can attest to that magic. Like Brierley, Nefkens was enjoying the life she had built for herself. Until, that is, she wasn’t.

“I was working as a communications adviser, and I was really focused on my career at that time,” Nefkens recalls over Zoom. “I had set goals for myself; in five years, I wanted to be a senior communications adviser, and five years after that, I wanted to be a manager of the communications department.

“I achieved all of these things. I spent a lot of hours on working, working, working. Not only physically, but also in my head. I had everything I wanted. I married a man who was also working a lot. Life was good.”

However, she soon began having physiological warning signs – tension headaches, nervousness, and more – all of which she chose to ignore. Then, the ball dropped.

“In just a month or two I lost all the things that I thought made me who I was; the work, the marriage, the money – all the security I thought I had was suddenly gone.”

Like Brierley, Nefkens sought answers along the Camino, starting her trek near Paris, taking one of the most popular routes, the Camino Frances.

“In the beginning, it was really hard: I was all alone there in France, I really didn’t speak the language, and I cried a lot.”

However, as per the popular phrase shared among the route’s faithful pilgrims, “the Camino provides.” In Nefkens’ case, it offered a sympathetic ear.

“I started to know others like me,” she explains. “I recall meeting a German woman, and by coincidence – or perhaps not – she shared a story that was very similar to mine. There was a real connection there.”

Nefkens communed with her fellow travellers, sharing albergues (Spanish hostels), and coming to consider them as extended family.

“I often roomed with 10 or 20 other pilgrims. We would sleep, get up early, share breakfast, and then simply start walking. That is the life of a pilgrim. I was never alone, on any single day on the Camino from Paris to Compostela.”

As her 2,000km journey continued, she supported travellers who were new to the trails

“Helping other pilgrims gave me a renewed purpose.”

Arriving at the steps of the Cathedral of Santiago three months later, Nefkens knew that she had been changed forever. Soon after her tour, she accepted a job at a travel agency specializing in Camino excursions, and eventually cofounded her own travel agency, WAW Travel, with her fiancé, Roberto Santos, who had been born and raised along the Camino.

“I lived in Santiago de Compostela for a year,” adds Santos, jumping into the Zoom chat with Nefkens. He gives a nod to the city’s Celtic culture, pointing out a charming pub in particular. “Casa das Crechas is really close to the Cathedral of Santiago, and that is where all the people who have Celtic roots meet. There, they play music, sing songs, and read poems. It is a bit surprising, but their dedication to preserving Celtic traditions is inspiring.”

Nefkens’ aim with WAW is to help other women through the Camino and show them that they can balance a life of career and family with self-care and self-reflection.

“That is my personal mission, because I am an example of this. I can give you 20 other examples of this among my close circle of friends. I talk with a lot of women, and many of them are suffering from something. I learned the hard way that, in the end, you need to take care of yourself before you can take care of others.”

She has been back many times since making her first pilgrimage, across several different routes, both for professional and personal reasons.

“This year, I will be walking again, to Santiago de Compostela. They say it is like a virus – except that this is a positive one!”

“There is something very real called the Call of the Camino,” Brierley chimes in, adding that even those who don’t complete the whole 2,000km trek on the first try always seem compelled to finish it on another occasion “Once the Camino calls you…I don’t know anybody who didn’t start it who didn’t either finish it, or come back to finish it. It is that powerful.”

As noted by both Brierley and Nefkens, there is no one way to take the Camino. There are 12 major recognized routes, denoted by stone way-markers that point to Santiago de Compostela, and some are larger than others. Some are even smaller by design, to make it easier for people (many who may not have the privilege of taking three months away from everyday life) to complete their journeys and earn their Compostela certificates.

One such pilgrim is Maureen Summers, a Halifax, Nova Scotia woman who first walked the Camino with a friend from Vancouver. They couldn’t make the whole journey in their limited vacation time, so they endeavoured to try again when the pair happened to be in Scotland, where Maureen was visiting her husband’s family.

“It was fabulous, just an amazing experience,” she shares, explaining that she and her friend took a day in Dublin to walk some of the Camino Ingles. We decided that we couldn’t not go back and finish.”

The Camino Ingles is also known as the Celtic Camino, as it would have been the start of any Irishman’s trip to the mainland, arriving in the aforementioned Finisterre, to trade, or to follow the Camino themselves. Brierley has written his most recent guidebook on this Camino, noting that he hopes to promote it and other smaller routes that don’t see the same numbers as the Frances and other, more well-trodden paths to Santiago.

“Partly what I am trying to do is move the heavy traffic off the Camino Frances – a quarter of a million people trudging along the route. There are lots of ways into Santiago. It helps to spread the economic and cultural benefit to remote parts of Spain, which could well do with what they call the ‘pilgrim dollar.’”

Lesser-known routes were the least of the worries of anyone relying on the “pilgrim dollar” the last few years, though. Just like everything else, the Camino was effectively shut down at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and is only now starting to open again to international travellers.

Summers is currently the co-coordinator of the Halifax chapter of the Canadian Company of Pilgrims, a national organization that connects Camino enthusiasts to one another, and helps provide information sessions and local community walks, among other things.

“Many countries have some type of association that supports people in their interest about the Camino, and in preparation for doing a Camino,” she explains. “And these provide a community when one comes back from a Camino as well. Some of the chapters run weekly walking groups, while others have annual or biannual group meetings, featuring different guest speakers and doling-out information on what you need to take.”

Of course, with a worldwide viral disaster making international travel almost impossible, the Canadian Company of Pilgrims – and their 19 chapters – are essentially in a holding pattern for until things get back to some semblance of normalcy. However, that doesn’t mean the group was sitting on their collective hands; as mentioned before, Summers and the other members of the organization know that “the Camino provides,” but this time, it the pilgrims are providing for the Camino.

“The Camino is sleeping,” she acknowledges, a bit mournfully. “However, we are doing what we can to keep it alive by helping those who are desperately trying to keep their business going in some of these very small places.”

Thus, a fundraiser was born.

“The intent of Keep the Camino Alive is to enable Canadians and our members to donate through the Canadian Company of Pilgrims,” explains Summers. “There has already been over $35,000 raised, and donations sent to many albergues. That money is being used to get plexiglass installed, and new beds that conform with Covid-19 restrictions. The fundraiser will continue until the end of 2022, as we don’t want to see that infrastructure destroyed.”

It is important that this Camino infrastructure is in top order, because soon, there could be even more pilgrims making use of it.

“There is very much a feeling of hope in terms of the Camino coming alive again,” says Summers. “They are expecting, throughout the year, about 500,000 people will walk Caminos.”

“All the hostels, all the different associations, everybody is in fever pitch,” adds Brierley. “There is this massive, pent-up demand, people are aching to get onto the Camino. I think we are going to see a surge of interest for two reasons. One is the pent-up demand. But two – and probably more importantly – the pandemic has forced people to reflect on their lives. They have lost jobs, or lost loved ones, and are on a bit of a wake-up call. They are beginning to ask those deep, existential questions, like what is this life all about?

“Those of us who have walked the Camino, in order for the experience to be of any relevance to the world we live in, we have to bring the Camino home with us,” says Brierley. “Part of the efficacy of the Camino is bringing back what we have experienced and learned and sharing it with others who might need some sort of spiritual awakening.”

Story by Chris Muise

Leave a Comment