For ancient Celts, the festival of Samhain – midway between the summer equinox and the winter solstice – marked the transition between the days of light and life and the onset of winter darkness. Believed to be a time when the veil between the world of the living and the world inhabited by the spirits of the deceased was at its thinnest, it afforded departed souls an opportunity to return and make their presence felt amongst the living.

As the pagan past is recollected in the spooky costumes and carved lanterns associated with modern-day Halloween, a group of Dalkeith artists has ensured that six of the town’s so-called ‘witches’ of yesteryear will be apparent to residents this October. For Mary Blair, chair of Dalkeith Arts, “It is an opportunity to pay our respects to some of the souls of the past and to reflect upon our community’s role in their persecution and deaths.”

Dalkeith, situated to the south-east of Edinburgh, lies in the council area of Midlothian. Although modern boundaries have changed, it was – and remains – conterminous with East Lothian, one of the historic counties infamously associated with Scotland’s witch hunts of the Middle Ages. Although there were few areas of the country that escaped the waves of paranoia generated by the power of church and state colliding with pagan beliefs and superstitions, it was along the south coast of the Firth of Forth from Edinburgh to North Berwick where one simmering cauldron boiled over – having been stirred overzealously by King James VI.

The Scottish courts were not unique in their desire to exterminate those considered as cohorts of the Devil. The fervour to hunt down and execute witches resulted in the Witch Trials of Trier, Germany, that saw over three hundred and fifty persons burned to death between 1587 and 1593. The realization that so many witches could be living amongst ordinary citizens rippled across Europe, fueling the Copenhagen witch trials of 1590 and giving rise to the burning of a further 17 souls. These trials would not have escaped the attention of James VI who was betrothed to Anne of Denmark. In September of 1589 Anne set sail for Scotland, but the journey was beset by a series of problems and unfavourable winds, culminating in a violent storm that forced her fleet to shelter in Norway with the Danish Admiral blaming witchcraft. Undaunted, James set sail for Norway, but he too was beaten back by a storm before eventually making the crossing. Married in November 1589 in Oslo the return journey to Scotland was also affected by storms. James became convinced that supernatural forces had connived to kill the parties and prevent the union. His suspicions were confirmed when Geillis Duncan, a young maid from Tranent, East Lothian was accused of witchcraft by her bailiff master. Subjected to horrific torture she confessed to being a witch and to whipping up the storms that almost sunk the royal fleet. No doubt in the hope of ending her torment, she provided the names of other ‘witches’ who had conspired with her. This gave rise to the North Berwick Witch Trials of 1590-1591 that saw some seventy persons rounded up and accused of witchcraft. James took great interest in the trials, personally interrogating Duncan.

It is impossible to confirm exact numbers, but records reveal that many were tortured, hanged and burned.

The torture of witches might involve incarceration in cold, insanitary conditions, crushing the fingers with pilliwinkes (thumbscrews), the wearing of spiked collars or muzzles, part strangulation and the deprivation of sleep that would produce sought-after hallucinatory tales – likely influenced by the inquisitor. Additionally, there was the humiliation of being stripped and every part of the body being searched for any blemish that could be construed as a mark of the Devil. Many trials involved the highly paid, specialist services of witch-prickers who would insert long, sharp pins into every part of the body until they claimed to find a place insensitive to pain and that did not bleed – another sign of belonging to Satan!

In 1591 James commissioned a pamphlet – Newes From Scotland – that made clear the exact nature of the horrific torture Duncan had endured prior to her execution. In 1597 he published Daemonologie – an alleged philosophical and theological work about sorcery, werewolves, vampires and explaining why witches needed to be expunged. Although James VI passed away in 1625, the waves from the North Berwick trials washed across East Lothian, reaching the town of Dalkeith which, shortly before the arrival of Reverend William Calderwood in 1659, had become known as ‘a town where all witches were burnt’. As parish minister, Calderwood reinforced the town’s reputation by making it his personal mission to root out the witches living within the community. Assisted in his macabre hunt by a local headmaster he was responsible for weekly witch trials, the torture of dozens of women and the hanging and burning of innocent souls. Inside St Nicholas Buccleuch Parish Church in Dalkeith is an engraved memorial. In Latin, it extols the virtues of the Reverend Calderwood as a much loved father and respected minister of the parish!

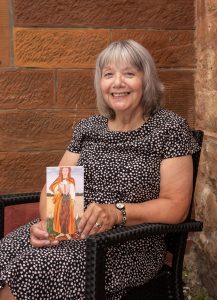

In 2020, Dalkeith Arts, in conjunction with One Dalkeith – a charitable trust founded to improve local community life – undertook a project in memory of some of those who were tried and executed as witches. It would serve as a reminder also of the town’s role in this unsavoury aspect of Scottish history. Ten local artists were each allocated a panel designed to fit on the external wall of the One Dalkeith building in town. With the help of a local historian each artist was given a choice of a subject for their panel. Three of the panels depict buildings and places in the town associated with the witch trials, while another features the notorious, witch-pricking charlatan, John Kincaid from Tranent.

The remaining six panels show fictionalized interpretations of six of the women tried for witchcraft:

Christian Patersone – accused of attending witches’ meetings.

Janet Cook – accused of sorcery and cursing to cause death and damage and of being part of a demonic pact.

Issobell Fergussone – accused of bearing the marks of Satan.

Beatrix Leslie – accused of changing into a dog, causing a mining pit to collapse through cursing and of meeting Satan.

Jenet Davidson – accused of spreading disease through cursing and attending witches’ meetings.

Katherine Casse – accused of claiming satanic powers and of causing death through cursing.

All bar Katherine Casse were found guilty and were strangled and burned in Dalkeith. The fate of Casse is not known.

For Blair, the images sought to challenge the typical portrayal of witches as wizened old women, “These are portraits of people that could be walking around Dalkeith today.

“It is a chilling thought that these were ordinary women, caught up in a time of terror and who ended up suffering a terrible fate.”

Collectively, the works represent more than just seven individuals and a few iconic buildings. Looking at the size of the paintings and the height at which they are displayed it appears as though the figures look down on us from another time. Kincaid appears arrogant and self-assured. The women are ordinary, dressed according to their time but portrayed alongside supposed animal familiars. They don’t look accusative but rather appear as we accused them. Representing all those affected by the infamous witch trials they seem to ask the simple but soul-searching question – why?

Story by Tom Langlands

www.tomlanglandsphotography.com

www.dalkeitharts.co.uk

Photographs courtesy of Keith Inglis

Leave a Comment