To be a pilgrim walking the Celtic Camino in Galicia, you need to be in possession of two essentials: a pair of magic boots and an appetite for shellfish.

Heading up through the woods above the fingers of the north-west Spanish coastline in May, the air is brisk with breeze, but when the rain comes down as all-penetrating as the Irish mizzle, no overnight dehumidifier un-dampens your sodden walking boots. Part of the pilgrim’s penance: you have to put them back on in the morning and pray for a fine day.

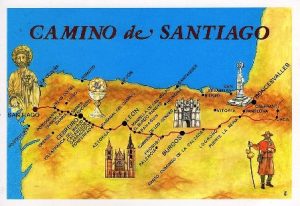

My daughter Miranda and I have flown to Santiago de Compostela to walk 100km of the Celtic Camino over five days, starting in Noia, renowned for its shellfish harvested in the nearby rias – inlets – since it became a fishing village more than 1,000 years ago.

It is Sunday, and apart from two cafés on the wide square brimmed by the medieval church of San Martino, nothing is open bar the Tasca Tipica.

The point of the first meal anywhere new is, for me, that it should offer insight into the kitchen and garden of the place you find yourself in, which, in this case, is the sea. Before the racións, which Miranda, in her fluent Spanish, has ordered, black-crusted bread arrives with slices of tetilla. Originating in Galicia in the Thirties, the small breast or tetilla is shaped like a flattened cone topped with a nipple.

Tetilla is defined by its natural, straw-coloured rind and its buttery, clean flavour. It is often eaten with raisin nut bread or quince cheese.

We move on to a plate of navallas, razor clams charred with wood smoke, tender pulbo á feira – chunks of octopus smattered with pimenton – and a plate of warm piquillo peppers stuffed with bacalau, pounded salt cod.

In the morning, we set off from the little Hotel Elisardo and head uphill on a street where every garden has green, unripe lemon trees, hens scratching, cabbages, potato plants, fig trees, and its own granite hórreo – grain store for storing sweet corn – perched on pillared mushroom stones to keep the rats out.

We enter the woods and begin our ascent through pine, oak and the ubiquitous eucalyptus trees grown for paper. We see no one walking the hills and, since this Camino is a forgotten coastal route marked on old maps of Galicia as one of the ancient paths to Santiago de Compostela, the few inhabitants we pass greet us with curiosity, each sprawl of houses quiet but for their alarmingly vocal dogs or the scrape of a hoe. There isn’t a hamlet without a cruceiro at its heart. Built from the 14th to the 20th centuries, these crosses are as much a symbol of Galicia as the hórreos.

To the left of us are ragged bays, mussel rafts, islets and crescent ribbons of ochre sand. Passing a row of hórreos, we walk a carefully laid stony path bordered by tall, slim tomb-shaped stones separating giant cabbages from the Camino.

We arrive in Muros, a working port, via a sweep of causeway where, its being low tide, two small figures are digging the sand for razor clams. All along the promenade are white houses whose first floors have closed glass balconies, known as galerías, from which the occupants can look out in sun or rain. Casa Petra is mid a row of unpretentious restaurants opposite the port.

If you are unacquainted with the Costa de la Muerte – the Coast of Death’s – most sought-after, perilously acquired inhabitant, I can only say that our excitement at being offered the holy grail of shellfish clearly surpassed our waiter’s expectations. Percebes – goose barnacles – live attached to rocks on the exposed Galician coast, where percebeiros risk their lives to gather them. They can make up to €300 (£230) per kilo at auction on the eve of a festival. We ordered a plateful for €16 (£12.50). Purists say that they should taste of the Atlantic surf and the plankton on which these creatures feed.

If you are unacquainted with the Costa de la Muerte – the Coast of Death’s – most sought-after, perilously acquired inhabitant, I can only say that our excitement at being offered the holy grail of shellfish clearly surpassed our waiter’s expectations. Percebes – goose barnacles – live attached to rocks on the exposed Galician coast, where percebeiros risk their lives to gather them. They can make up to €300 (£230) per kilo at auction on the eve of a festival. We ordered a plateful for €16 (£12.50). Purists say that they should taste of the Atlantic surf and the plankton on which these creatures feed.

The trick is to cook percebes briefly in roiling water. When you have snapped the claw from its stalk and wheedled out the stem of orange-purple flesh, you will, if you are thrilled by such things, understand that no comparison reflects the experience. To say that percebes taste a little like a combination of crab, oyster, urchin, shrimp, is more confusing than accurate.

Next, a platter of lightly steamed clams, razor clams, mussels and gambas in a white wine and pimento broth as steeply piled as the hills we have scaled, so we feel justified in opening, peeling, sucking and spooning until the land is leveled.

From our room at the top of the Hostal Ria de Muros we hear the seagulls squealing in the early hours. In the morning, the port is misted over like a windscreen with soft rain. We head to the café next door for breakfast, but the surly woman behind the counter offers only bad coffee and a packet of stale cake. Miranda exhales a polite tirade of requests and explains we have a five-hour walk ahead of us, but clearly nothing is more resistible than a pair of backpackers never to return.

For three hours we head from the rain-blurred coast into the woods, dripping and determined, up gorse- covered dirt tracks, our waterlogged boots weighing on us like anchors.

Virtue has its own rewards, and when we finally get to the coast, the rain stops. Passing the Punta Insúa lighthouse, we sit on the garden wall of a closed up house to eat our picnic and are surprised by a weasel tame enough to sit and survey us, white throated and caramel furred, from touching distance. Known as guarduna in Spain, the weasel is seen as the guardian of the house.

We clamber across rocks, push through spiky dune grasses and switchback on to the dramatic emptiness of a two-mile strand, silver where the low tide is creeping in and pale gold behind. Only our shadows cloud the sand, while ahead of us, the mountains are patched with the dark reflections of the clouds above.

Our itinerary declares today’s walk should take five hours; we have walked for seven. And we are route marchers, not Sunday strollers. We have wildly overshot the turn-off for Carnota.

Arriving at the Prouso Pension, the owner, Pedro, leads us to the kitchen, extracts trays of chipirones – baby squid – and wings of fresh skate for us to choose from, which his wife cooks with simple precision in the Galician style, finished with olive oil, pimenton and boiled potatoes.

Arriving at the Prouso Pension, the owner, Pedro, leads us to the kitchen, extracts trays of chipirones – baby squid – and wings of fresh skate for us to choose from, which his wife cooks with simple precision in the Galician style, finished with olive oil, pimenton and boiled potatoes.

One of the points of walking this un-peopled Camino has been the opportunity for Miranda and I to travel and talk or remain silent with the un-justifying ease that one has with family. Once you have been walking for several hours, keeping a rhythmical stride, a curious calm descends; you become almost unaware of everything outside the moment and the landscape.

We hear the market setting up first thing in the morning. We buy black tomatoes, early cherries and the rest of our picnic from an outstanding stall of organic produce: golden empanadas filled with pork, salt cod or tuna; cracked-topped loaves polka dotted with black raisins and walnuts; young, waxy-skinned cow’s cheeses; and eucalyptus and pine honey. The stall holder gives us a bottle of homemade wine to accompany our feast and we set off.

The sky is murky grey blotting paper, the track brightened by butterflies, cornflower blue or yellow with peacock-blue bodies. We see cup and ring markings etched into the rocks dating from the Megalithic period and an outcrop of rock thought to be the site of a pagan altar. Monte Pindo rises ahead and we see our distant goal, Finisterre, the end of the earth.

A rigorous climb of 1,550m ends high up in a whirring wind farm from where we walk through green pastureland punctuated by small villages. Our only encounters are with some fearsome unguarded guard dogs. We cross a vast, flat-calm lake, the dizzyingly set dam across it hundreds of feet above where its waters fling themselves into a canyon below. Still nobody.

The Casa Santa Usia on the lake is a beautifully restored stone farmhouse where we peel off sodden boots and lie by the peaceful water after our six-hour trek. Dinner ends with torrija, traditionally eaten in Lent and originating in the 15th century to use up stale bread – the Spanish version of French toast. The bread is soaked in milk warmed with cinnamon and lemon peel, wrung out, and fried in brûléed sugar to crisp. Manna to the hungry marcher.

The next day we walk to the charming sea town of Corcubión with its palm-treed promenade, 12th-century Romanesque church and back alleys whose stone houses are fronted by exquisite wrought-iron balconies and elaborately carved great doors. We lunch at the Cafeteria San Martin Restaurante, noisily besieged by a full house of local diners cracking shells as the waiters speed round the tables bearing trays of mussels, cockles, scallops, razor clams and fried fish.

The following day we head for the lighthouse. We have joined the established Camino, and it is something of a jolt to share our solitary path with bunches of pilgrims. The approach to the end of the earth is tawdry with souvenir stalls, but nothing detracts from our sense of awe as the great blue merges with the sky beyond the lighthouse’s watchful presence.

We spend our final night in Santiago de Compostela. Since the early Middle Ages pilgrims have come to the Romanesque cathedral, the reputed burial site of St James. The Rajoy Palace faces the cathedral, making this square a place of breathtaking architectural beauty. We walk the old city, its back streets opening into squares and verdant gardens, and in the evening we accompany Adrian Comesana, owner of the jewel of a hotel Pazo De Altamira that we are staying in, to his favourite tapas bar, Gato Negro. The empanadas sardinas and berberechos – cockles, the emblematic shells of the pilgrim – are as salty sweet as you could wish for.

Adrian is insistent that Miranda and I experience the best traditional dishes, so we move on to Ocurro Da Parra for gambas coated in crisp batter served with romesco and croquetas made with slow-simmered béchamel.

When we leave the following morning, we determine to return. This is not a city to flit in and out of – it is beautiful and enticing at a majesterial level, while retaining its charming parochial, local identity. And it is the perfect place in which to indulge after the pilgrims’ path has been accomplished.

Story by Tamisan Day-Lewis / Source: Telegraph.co.uk

I loved this post! “a pair of magic boots and an appetite for shellfish”, hahaha, I totally agree!