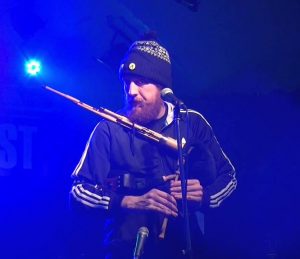

An award-winning Gaelic singer, poet, producer and piper, Griogair Labhruidh has worked with some of the biggest names in contemporary Celtic and World music. His love for Gaelic culture stems from his roots in the Gaelic tradition of both North Argyll and North East Skye. He is a PhD candidate and regularly gives talks, workshops and classes both at home and abroad on Gaelic culture. He lives on the Isle of Skye and spends most of his time writing, recording and producing music, and lecturing at the Sabhal Mòr Ostaig Gaelic College. He has contributed to both film and stage and is a part of the multi-million record selling Afro Celt Sound System collective. His current project fuses traditional Gaelic music and poetry with Hip Hop and other contemporary genres.

Tell us about your heritage.

I am a Scottish Gael. I was brought up in the tradition of Highland bagpiping amongst the Highland diaspora of central Scotland – more specifically, in the hinterlands between the Highlands and the Lowlands, an area known as the Leamhanachd. My father’s family have been playing the pipes for several generations, as have my mother’s, and both were well known for this. My piping ancestors belonged to a musical tradition which is intrinsically connected to the now almost-extinct Gaelic traditions of North Argyll. I have devoted my life to unearthing the depth of this tradition – the dialects, the songs, the place names, etc., and I was lucky to have learned much from the area’s last speakers. In recent years I have been drawn more to my roots on my mother’s side in the North East of Skye, where Gaelic is still spoken by a large percentage of the population.

When and why did you start playing music?

When and why did you start playing music?

I started learning the Highland bagpipe at the age of seven, but I was already competent in its repertoire, having been exposed to the tradition since my birth. This was mainly through the influence of my parents, both of whom were steeped in the traditions of the instrument, along with my mother’s brother who was a prominent figure in classical Highland bagpipe circles. I am told that I was able to sing some of the repertoire before I could even walk.

Are they the same reasons you do it today?

I started playing music because of my family and my roots. I still perform music for this reason, though is has been amplified through my better understanding of my place within the overall stratum of Gaelic tradition. There are other reasons why performing is important to me, including the increased urgency with which Gaelic artists must meet the challenge of preserving our fast-disappearing culture and ways of life.

What are the challenges of the vocation?

One of the greatest issues faced by myself, and for others of my generation, is being at the crossroads between an unbroken and very-old indigenous tradition – which was intrinsically tied into the land for countless generations – and modernity, with its trappings and added pressures. The Scottish Gaels and their culture have been oppressed for many generations, and the lack of education for Scotland’s indigenous culture can be frustrating. The challenge for an artist like me is to use my art and my abilities to break through inter-generational barriers.

What are the rewards?

The greatest reward is being connected to an authentic tradition. It is a true privilege to be the representative of my culture. The connection with generations past, and with the land which we have occupied for all these centuries, is a deeply spiritual one. In my spare time I like to spend hours in the sacred places – the mountains, the lochs, the cleared villages where my people lived – reflecting on their stories, their songs and their beliefs in the other world, thus tying myself into that which is much greater than I am. If I can do anything for my audience it is to bring this to them so that they might have a deeper connection with themselves, with each other, and with the land. The world is in an ecological and spiritual crisis and those of us who are close to our roots are best equipped to effect change and facilitate the healing of indigenous cultures, the land, the planet, and the heart of humanity.

Is your creative process more ‘inspirational’ or ‘perspirational’?

Both. The initial stages of the creative process are completely inspirational. When a musical project nears completion, however, it requires hard work to pull those moments of inspiration together. I enjoy all stages of the process.

What makes a good song?

What makes a good song?

A good song is characterized by authenticity; it should be a true representation of the artist’s inner landscape and connect the listener with this on a deep level.

What are your thoughts on the current state of Celtic and Gaelic music?

I question the word Celtic and its usage in musical circles. As a Gael, I believe that Celtic refers to the culture of my people, the Gaels, and to those of Celtic origins. Over the years I have heard various styles of music – mainstream competitive piping, Scots fiddle music, Irish session music, and even bluegrass – being described as Celtic. Although these styles may be influenced by Celtic culture, unless there is some content which is related to indigenous Celtic culture and language, a better term to classify these genres might be “folk” music. With Scottish Gaelic specifically, I believe that attitudes are changing. However, within the performer community itself, there are difficulties with both the commitment to understanding the depths of the traditions and the increased commercialization of the culture. This is likely pertinent to many world cultures where the performer community was once based in a particular place and had very different parameters from those associated with formal commercial performance. It is only natural that some of the aesthetics of the indigenous tradition would be transformed over time. This is not a recent phenomenon. My concern is that the true essence of Gaelic music is being lost within contemporary interpretations. In saying that, it is encouraging to see the younger generation engaged at some level in the culture.

Is enough being done to preserve and promote Celtic and Gaelic culture generally?

No, not nearly enough. In my lifetime there have been numerous attempts to promote the culture, including Gaelic medium education, the establishing of a Gaelic TV channel, and various other national-level movements. These have all helped. However, what we need is to change our way of thinking as a nation and a complete cultural shift in our views towards Gaelic, the Gaels and who we are. Over the past 100 years the traditional body of Gaels has been greatly diminished, leaving a gap in the cultural landscape. This gap has generally been filled by the ideas, way of life and cultural norms of non-Gaels. As such, the Gaelic identity has become endangered and the choices for the indigenous people are now either cultural assimilation or annihilation.

How can this be improved?

First, it would be greatly helpful if people would acknowledge Gaels as the indigenous people of their land. And education should be an utmost priority for the Scottish Government; we must invest in, nurture and develop the remaining remnants of our once-great civilization which are

now to be found only in a few areas of the islands of the west. A lot of people want to turn Gaelic into just another modern language. But being a Gaelic speaker is different from being a Gael; Gaelic is not just a language – it is a whole world connection and a philosophy and, if we are not careful, it will be forever lost for future generations. Sorley Maclean, the great Gaelic poet, believed that the best chance for Gaelic to survive will be via Scottish independence. This idea is echoed by many cultural theorists who believe that a nation that is in control of its own destiny is the only way for it to truly, successfully achieve cultural revival. And though Scotland is a country with mixed traditional identity, we have yet to come to terms with either our history or our dual identity as a nation. As a Gael brought up separated from his indigenous ancestral environment, and coming from a mixed Gaelic background, I have had to negotiate my own identity. Scotland, as a nation, must do the same thing. That said, it must be asked, is Scotland really a nation? Or are we, the Gaels, a separate nation unto ourselves? Should we ourselves be looking for some sense of self-autonomy as a people?

What’s on your creative agenda for the rest of 2019?

I am currently in the final stages of producing my first album in 12 years. This has been a very challenging undertaking, having started out as a bedroom project and becoming something much more ambitious. The recording brings together all my traditional influences, including my Gaelic poetry, piping and singing, with my non-traditional music interests. The project began as a protest album and a platform to express my own disillusionment with the cultural status-quo regarding Gaelic and the Gaels. It has now grown into more of a celebration of what is possible when taking this tradition and pairing it with jazz, funk, soul and west African music. My time playing with Afro Celt Sound System has helped me see ambitious projects like this through to fruition, and I have been fortunate enough to work with some of the best musicians I have ever met in my life on this album, including some of my friends from my university years and a top African musician. In recent years, I have been focused upon evolving as a music producer and my hope is that this recording will display these new-found skills, get my message across, and – perhaps most importantly – inspire younger musicians to preserve the essence of indigenous Gaelic aesthetics while creating new soundscapes and traversing between genres.

Having visited Scotland recently Fall of 2019 and seeing first hand the beauty of the highlands and experiencing the nicest of peoples then visiting Culloden Moor battlefield being deeply moved by the Jacobite slaughter and being Scot on my Father’s side, I greatly appreciated the comment about Scotland taking back her independance and fully recognized Goverment. Then dictating her own destiny for her people. And then Gaels being declared its own indigenous people and appreciated for their culture and language is important before anymore of it disappears. I also am a fan of Griogair’s music and his voice. Well done interview!